Since time immemorial, audiences and filmmakers worldwide have long debated the inclusion or omission of intervals in their films. The length of films, the ‘Broadway bladder’ concept, the issue of engagement – all of these and many more such reasons are used to strengthen views by parties of either side. Filmmakers, especially, have long been divided over this matter.

Alfred Hitchcock famously said, “The length of a film should be directly related to the endurance of the human bladder.” And now, because Hitchcock said that films must only be as large as the audience’s bladder, he’s often quoted as defending the whole debate of having shorter films or Intervals in longer films. But he also said something about messages having their place at the post office, not the movie, and that’s not something we debate about.

Filmmakers, anyway, make films with and without intervals, and they can be good for the film or suit some films, like “Masaan” (2015), which was written with an interval in mind, or can hurt the film badly, like “Trapped” (2016), where the protagonist—a poor guy—is starving himself to death, trapped alone in an under-construction flat, and the viewers want a ‘break’ from watching it to have ‘coke and popcorn.’

There has never been unanimity about the inclusion or omission of Intervals in films – neither amongst the audiences nor amongst the Filmmakers. Filmmakers from all over the world have their own way about it. Tarantino made “Hateful Eight” (2015) with an inbuilt 12-minute interval for the multiplex version of the film, and he had his own reasons for it. Vikramaditya Motwane made “Trapped” (2015) without one and had his own (quite evident) reasons for it too. This makes the significant ‘break’ within films in no way a lesser creative choice than, say, a cut or a special effect.

A Motion Picture is a collage of footage and the gaps in between the footage. The inclusion of intervals, too, like that of other creative choices, such as the use of music, which again in itself is a collage of sounds and gaps within those sounds, is not very different from the concept of editing. After all, the interval is just another gap between the running images. However, the effects of this ‘gap’ are what create the whole divide.

Films are specifically edited, keeping in mind their effect on the audience’s mood. The impact of the lighting, the cuts, the POVs, the proportions, the pacing, everything is meticulously planned. Some of the directors like to specifically hold a dissolve for a couple of seconds before getting to the next shot. That’s how they find a way to relieve their audiences, one prominent example of which being David Lynch’s films, which are otherwise too much to grasp at once and which every now and then hold a blank screen for a couple of seconds.

Others find their own way to do so. Some filmmakers, like Mani Ratnam, whose films are so visually palleted, choose to use music deliberately with some scenes, and he says that it acts as a relief point, too. The music then acts as both a relief and a point when the audience connects more, too. Sometimes, the audience is watching so much, all at once, that at least the music helps them relax. Can there be a way to look at intervals similarly?

We all know Hollywood has long gotten rid of intervals, especially since the advent of sound. But there still are exceptions in modern cinema too, namely “The Irishmen” (2019), “Titanic” (1997), “Gandhi” (1982), “Once Upon a Time in America” (1984), “The Godfather” (1972), etc. But there are just a handful of them to name, and today, they’re not even susceptible totally to the length of the film alone. We have seen shorter films with intervals and extremely lengthy films with no intervals.

“Ben Hur” (1959, 3 hours 32 minutes) was almost three and a half hours long and had an inbuilt interval as a choice. Now, should this creative choice be respected? Of course. But so was Martin Scorsese’s latest masterwork, “Killers of the Flower Moon” (2023, 3 hours 26 minutes), and it didn’t have any interval. So, does that mean we get the right to slash right into the middle of the run time and slaughter the filmmaker’s creative vision? Because we want to boost our popcorn sales? No.

To look at the traditional idea of what a filmmaker wants to achieve through their films, it mostly is to make them so believable that the audiences end up feeling authentically and earnestly for the characters, at least in most of the parts. For such a goal, it seems entirely out of the world to plant a 15-minute ‘break’ in the film, with 20 ads, that would rather jolt them out of the whole experience and get rid of their engagement with the story. And a forced Indian interval, more so, would be a straight-up mockery of a sincere attempt to make the audience ‘feel’ with conviction.

But of course, we have our classic great films like “Mera Naam Joker”(1970) or ” Lagaan—Once Upon a Time” (2001), which would instead provide the audience with engagement and even tension within the framework of entertainment through films. They don’t mind the audiences returning to their real world in the between and helping themselves to the lavatory. It’s actually the most interesting to look at how Indian or, largely, even Asian audiences look at this whole business of watching films with or without a break.

The concept of intervals, in the case of plays, was instrumental and much needed also for the performers, as they used the time window to change costumes, shift scenes, change backdrops, props, etc., and, of course, also to catch a breath within the intensive performances, especially in physical theatre performances.

There is a whole long history of Japanese ‘Kabuki’ Theatres having almost hour-long intervals and additional filler scenes even after the Interval time was over, assuming that the audiences would arrive late (which they did too) even after the interval or the ‘Nakahairi’ interludes in the ‘Noh’ Theatre that would sum up the events in the first and second halves of plays, or even the Indian plays, where 4-6 Act plays were a widespread practice, which prominently had (and still do have) intervals after the second or third act. The same stuck with films and even went on ahead, as Raj Kapoor’s “Sangam” (1964, almost four hours long) and “Mera Naam Joker” (1970, longer than four hours) actually had two intervals.

For films like these, it is necessary to understand that the audiences, too, might have enjoyed these breaks. There often arises an urge within the audiences to savor the flow of their favorite films by having breaks between them. These breaks in such entertaining films make them last long and aid the audiences in being able to enjoy them to the fullest of their hearts.

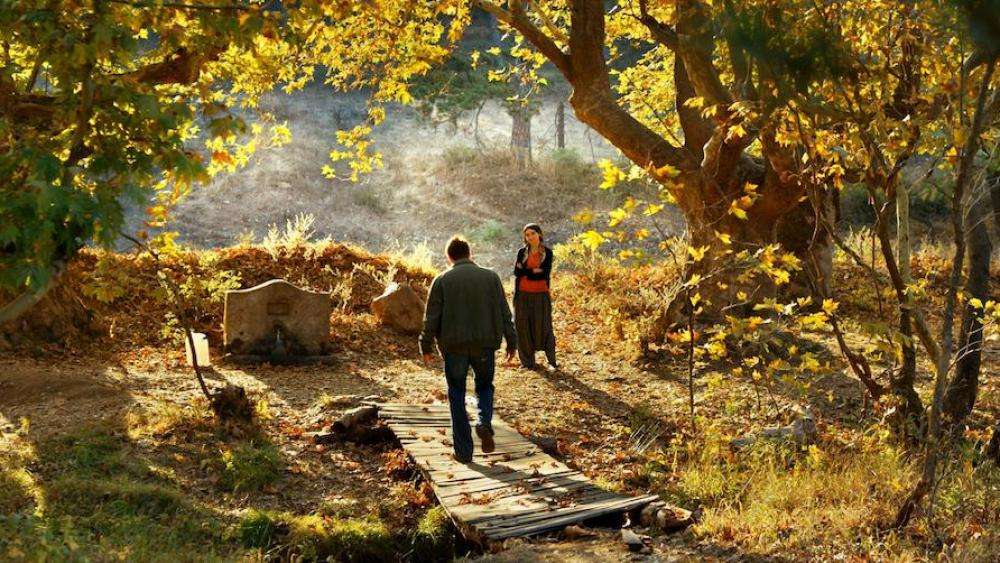

However, recent Asian films, like the ones from Turkey, Iran, and Japan, which are leading examples of authentic storytelling in terms of quality and innovation in style, have different tales to tell. It is necessary to look at films, for instance, Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s films, namely, “The Wild Pear Tree” (2018, 3 hours 8 mins) or “Winter Sleep” (2014, 3 hours 16 mins), which won the ‘Palme d’Or, where there isn’t even a lot of action. In these films, there’s a lot of dialogue, most of which are routine exchanges and have a very rich philosophical subtext to them. It is, of course, also paired with great visual poetry but still is verbally abundant.

Audiences are expected to listen to people talk for long periods without a break. Kiarostami’s Iranian films are another example of a similar style of filmmaking. He is very often, even jokingly, known to put actors – his protagonists, in a car and just have the audience drive off with them, too, participating in the journey with these characters. These films, irrespective of their lengths, are known to have a somewhat calmer effect on the audience on the surface level, but they are still verbally abundant.

This style, too, is in the filmmaker’s due right. The filmmaker wants the audience to walk (or drive) with the characters, to be with them more and more, and they do have evidently good results without an interval. However, having a ‘pause,’ a break too, is equally necessary for all artistic consumption. Have you ever wondered why so many of the regular gallery-visiting spectators claim to cry for hours standing in front of a Rothko, which is almost a painting of specifically ‘nothing ’?

Moreover, these paintings are not more than just two plain brush strokes of two different colors. Quite evidently, these paintings have more to them, and they somehow have something to do with catharsis that leads to the emotional response. A break, a pause, or a moment of relaxation from all the mental masturbation that sometimes seems inevitable in the ceaseless consumption of art leads to this emotional release, and this release, this response, forms its own art in itself, too.

Although not to say that a Rothko and a Film Interval are comparable, films still, being an audio-visual medium, find themselves somewhat in the same realm when talking of expression. Thus, understanding these concepts that might have an explanation for the whole Interval business and its effects helps. Today, however, more often than not, they are seen just serving the multiplexes, boosting their popcorn sales, and the ‘Broadway Bladder,’ which is basically the alleged need of the Broadway audiences to urinate every 75 minutes. In such a scenario, educating oneself amongst all the chaos and finding a Golden Median seems the sanest thing to do.

Finally, as discussed before, intervals only make complete sense to retain their hold over the film experience if they are considered a style of editing and not the only way to watch films. If we consider them a way to engage and communicate with the Audience, or even an opportunity for the filmmaker to ruminate on the visuals, they can be taken as a part of the film rather than a hiatus in a film.