Understanding Cache and The Return: There are multifaceted stories that encourage the audience to embark on them from varying perspectives. Andrei Zvyaginstev’s debut feature film, The Return (2003), and Michael Haneke’s Cache (2005) have now aged more than a decade and are celebrated classics. Though both are set in distinctive geographical and socio-political contexts, the storylines seem universally appealing as they revolve around family and human relationships. It is interesting how these stories go beyond their peripheral narrative to unfold themselves as metaphors for the respective socio-political histories and consciences that they belong to.

We see a terrified couple in Haneke’s Cache as they receive an anonymous videotape featuring the exterior of their own home. They get to know they are under surveillance, and the mystery intensifies as they receive more of them. The slow-burn psychological thriller narrative of Cache indulges us in watching the mystery gets resolved. The childish yet disturbing drawings and the videotapes make the protagonist recollect an incident from his childhood.

The protagonist soon hunts down the person whom he believes is the culprit behind the inconveniences caused to him through those anonymous tapes. The man is the son of an Algerian couple who earlier worked for the protagonist’s family, and he gets adopted as his parents die in a riot. But the then-young protagonist hates this child and engages in some brutal acts to expel him from the family. He succeeded, and the kid was taken away to a shelter home and brought up under harsh realities. The protagonist now believes this man is taking revenge on him for the brutal acts he committed in his childhood.

While the story, on its periphery, is regarding a family and their inconveniences, it specifically represents the French conscience and guilt over the Paris Massacre of 1961. Algeria was a French colony at that time, and the nationalists were fighting for independence. A peaceful demonstration organized by the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN) on October 17th was turned into a massacre, resulting in a heavy death toll. The French government initially denied any deaths, but evidence later emerged confirming the killings. The French conscience of guilt is represented by Haneke, turning the whole story and narrative into a metaphor for guilt, dilemma, and a history of violence. Michael Haneke, in an interview, describes his film as a story of guilt and the denial of guilt that every one of us faces.

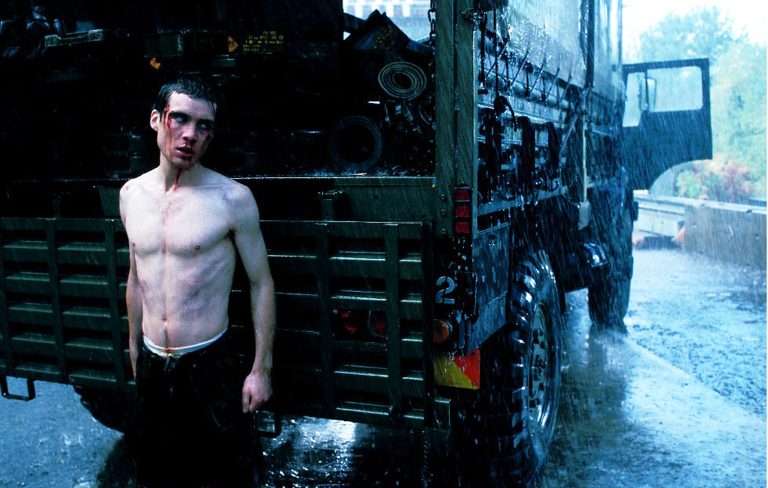

The Return captures the holiday trip of a father with his two kids. The father just reappeared in the family after a 12-year absence, and the kids were excited about his arrival. But soon, they become disappointed, as the father seems authoritative and nowhere comes close to their expectations. He appears determined to train the kids to adapt and cope with potential situations. While the elder kid stays loyal to his father most of the time, the younger one manifests his dissent. In the latter parts of the story, we see the father’s accidental death, and even in the midst of panic, the kids responsibly cope with the situation. A brief stint with their father has transformed and empowered them.

The way The Return replicates Russian history concedes that the film itself is a reflection of the land and politics in which it is made. The concept of the Soviet Union, the attitudes of the people at that time, and the insecurity experienced by its collapse can be traced in the film through the characters and events. Within the operational framework of the Soviet Union, there were loyal as well as dissenting voices. And its sudden fall did bring about a state of panic and insecurity. A glimpse into history itself can be seen intertwined within the narrative of The Return.

It is evident that every creative and artistic product might have these socio-political implications. And films are easily the subjects of political readings and critical studies. Abbas Kiarostami, the Iranian auteur, said, ‘Any film that is anchored in a society and any film that deals with humanity is necessarily political.’ Zvyaginstev’s The Return and Haneke’s Cache use this woven narrative to present an appealing story in the first place. And then reveals the intertwined socio-political contexts resulting in it becoming a complete metaphor.