The representation of women in Indian cinema has long been an issue of scholarly debate as many scholars have suggested that the representation of women, even after more than hundred of years of the development of Indian cinema, has largely remained marginal and most of the time, women characters are added to the narrative as an afterthought, which hardly adds any narrative value to the film, except playing stereotypical character and conveying the tropes expected from them in a patriarchal society. While there are millions of ways the representation of women can be done in Indian cinema, we will look at some of the representations to understand how mainstream Indian cinema often tends to objectify women or offer them a character sans agency. This kind of representation reinforced patriarchy in many different ways.

In the 70s and 80s, with the increasing output of violent action films, we find an increase in the representation of sexualized women and the use of sexual violence against women. While the coming of family and romantic films in the 90s did signal a decline in the representation of sexual abuse in cinema, it created a new or renewed stereotype of women – a docile, ideal woman, whose agency is subdued under the value system of a patriarchal family. The return of action films like “Dabangg” (2010) signaled the return of blithe sexual gaze and sexual violence against women.

On the other side of the spectrum are the alternative or parallel films which offer greater complexity and more nuanced portrayals of women, often charting into terrains uncharted by the commercial cinema. Ranging from “Mandi,” “Arth,” and “Bandit Queen” to “Fire” and recent films like “Lipstick Under My Burqa,” “Angry Indian Goddesses” etc provide a more sympathetic or layered portrayal of women, even though this clear cut distinction is highly problematic and should not be generalized. Taking the case studies into account, we will try to extract the relevant conceptual categories within which we can situate the politics of representation of women in Indian cinema. Also coming within our ambit is what happens behind the camera and the many trials and tribulations women have to face to be visible on camera.

The constant news of sexual abuses, casting couch, and allegations of #Metoo have considerably expanded our understanding of the murky world of glamour, wherein women are subjected and vulnerable to abuses and objectification even in real life. This conflation between the real and reel is something that will be the basis of our article. I have taken a few films from the 1980s, a dreaded decade of Indian cinema to show how, in order to desperately cater to the “interior audience”, referring to the small towns and semi-rural spaces, filmmakers developed tropes that reflected the voyeurism of the male audience. Female parts became more and more ornamental, and the female body was objectified to the extent, that a scene of sexual assault was inserted in the film, on the request of the exhibitors and distributors.

One must assume a degree of sensibility when dealing with issues like rape or sexual assault. Occasionally, we do find people finding humor in the wordplay over “Balatkar” (rape) in “3 Idiots,” but largely, even in Indian cinema, rape is an issue, which becomes the pivot for the male protagonists to go on a rampage and unleash his streak of violence, and the females are either expected to die or go vengeful. But this is only if the assaulter is projected as a villain or antagonist, who needs to be punished. If the sexual assault is committed by the protagonist, there are some ways the sexual assault either is justified or trivialized. A very problematic dimension of the representation of sexual assault is the way it is justified or even promoted as a legitimate means to exact revenge or to meet the ends of society.

Multiple tropes are connected to this representation ranging from the trope of the raped woman getting married to her rapist and turning the story into a tale of their consummating their marriage as a blissful couple completely negating the circumstances in which the alliance was formed. In such movies, the main concern of the raped woman and her family is about her marriage. The larger question remains – who will marry a raped woman? The man either out of guilt (“Satyakam,” “Hawaalat,” “Himmat,” or “Mehnat”) or forced by law and the society (“Benaam Badshah,” “Raja ki Aayi hai Baraat”) has to marry her. While in films like “Hawaalat” or “Satyakam,” the man is not the rapist but the man whose irresponsible behavior led to the rape. In “Himmat aur Mehnat,” “Raja ki Aayi hai Baraat,” “Benaam Badshah” etc, the rapist is married to her victim.

Here too, in all three circumstances, the motives of the rape are different. In “Himmat aur Mehnat” it is the lust for the girl accentuated by vices of drinking, in “Benaam Badshah,” the rape is part of a conspiracy for which the rapist is paid, and in “Raja ki Aayi hai Baraat,” the rape is shown as an act of vengeance. In none of these films, the protagonist is shown in a negative light, but rather a reckless man who is transformed due to his association with the girl. Particularly, in “Himmat aur Mehnat,” the entire subtext of rape is forgotten as if didn’t exist ever.

The most convenient way to undermine the implications of sexual assault is by associating it with either revenge or alcohol. Going one step ahead, we see the occasional justification of rape as legitimate means to “make a woman out of a girl”. In the film “Chittema Mogudu” (1993), the girl is raped by her husband, which makes her realize her own ‘feminine self,’ and her pregnancy is celebrated as the consummation of marriage.

Three common tropes are utilized to justify the act of sexual assault in Indian cinema. In the first case, the protagonist is shown as a troubled man, who has been wronged by the antagonists, and hence he is on the spree to take revenge, killing men and dishonoring women as an act of vengeance. In “Insaniyat ke Dushman” (1987), the protagonist rapes the girl as revenge for the rape committed against his sister!!

So, rape is used as a tool to avenge rape. Furthermore, the act of rape in the above-mentioned film is justified as: “Pyar ka Haq jo maine zabardasti hasil kiya” (My right of love that I took forcefully). The utter insensitivity of the logic denies the scope for the female protagonist to even voice her concerns. In “Insaniyat ke Dushman,” the rape case is dismissed because the perpetrator is a skilled lawyer who is able to prove the ‘promiscuity’ of the girl in the court.

In “Himmat aur Mehnat” (1987) the man in an inebriated state rapes the girl who had earlier berated him for his misconduct. Here, even legal recourse is not available to the girl as she has only one option left according to the tropes of Hindi cinema: suicide. Eventually, she is saved by her rapist, who slaps her for attempting suicide, and rather than feeling guilty or apologizing for her actions, he offers to marry her, which is seen as a perfect solution. The film “Raja ki Aayegi Baraat” (1997) mixes all these tropes together. The girl is raped by the protagonist as an act of revenge for insulting him earlier. A court case follows where the Judge in a ‘landmark decision’ orders the rapist to marry the girl he raped to prevent jail time.

In “Benaam Badshah” (1991), the man with no morals rapes a girl for money, and the raped girl rather than taking action against him pursues him till he makes her his wife. In “Paap ki Aandhi” (1991), the protagonist rapes a girl out of revenge because her brother presumably incriminated him falsely and gave incorrect testimony. He is served jail time not because of rape but because of the murder he committed in revenge earlier. And the raped girl is impregnated and bears the child for her life waiting for her ‘rapist’ to return.

In “Badlapur” (2015), we see a blurring of the line between the hero and the villain as the protagonist does all the heinous acts to avenge the death of his wife and child, including sexually assaulting the girlfriend of one of the killers multiple times and molesting the wife of the other killer before killing her as well. Although the act has not been justified in the film, the protagonist ends up facing no consequences for his act.

A subtype of the revenge trope is when the man attempts to avenge the wrongdoing by the girl through molestation but stops just in time to show that he is still a gentleman who doesn’t fulfill his carnal desires despite being physically capable of doing so. And this realization blooms into a ‘sense of love’ in many Hindi movies. In “Dil” (1990), both the protagonists indulge in constant mockery and mud-slinging at each other until the matter gets serious and the girl falsely accuses the boy of sexual assault due to which he is removed from the college trip. To avenge his humiliation, he abducts the girl and molests her saying that “I will show you what an actual rape looks like”.

Also Read: The 10 Best Hindi Movies of 2024

Eventually, he relents and doesn’t carry out the process of sexual assault leading to a romance kindling between the two. The romanticization of the “gentlemen’s behavior of not raping a girl” is a recurring trope in Indian cinema. In “Aag Aur Shola” (1986) the girl incriminates the boy by forging a fake letter accusing him of teasing girls. To take revenge, he uses the opportunity of the enactment of the ‘Cheer Haran’ scene of ‘Draupadi’ in the college skit to disrobe and forcefully kiss the girl on stage. No wonder, they also end up together soon after. Promoting forceful and violent sexual behavior is allegedly a way to show the intensity of the love of the man.

In “Manoranjan” (2006), the protagonist gets frustrated for being falsely labeled as a ‘rapist’ and when his love interest does the same, he loses his cool and tries to molest her saying “This is how a rapist behaves!!” Such scenes reflect the irony of the situation as the protagonists try to prove their clean character by doing exactly the opposite. In “Chor Machaye Shor” (1974), the male protagonist is falsely implicated in a sexual harassment case and sent to prison due to the testimony of his love interest. He escapes the prison and tries to molest the lover to avenge the wrongdoing.

In “Auto Shankar” (2005), the male protagonist avenges the wrongdoing by the female protagonist, comes to her home, tries to molest her, tears her clothes, and stops just in time to deride her saying “You are not worth it”. The threat of sexual assault exists in more than one way in Indian cinema ranging from the ‘Taming of Shrew’ in films like “Dharam Veer” (1977) and “Sangdil Sanam” (1992) etc, wherein the male protagonist spanks and forcefully kisses the girl to domesticate her and make her subservient.

A more subtle representation of the same can be seen in films like “Rehna Hai Tere Dil Me” (2001) where the male protagonist justifies his act of using someone else’s identity by pointing out his good intent of else “he could have done anything with her in these few days”!! More than anything, such scenes are used to titillate the audience while maintaining the sanctity of the protagonist’s character nature.

Another subtype of revenge will be a forced sexual act out of anger and frustration stemming out of the male, and its satiation through the violation of the woman is seen from the perspective of the man, and the perspective of the woman is repeated to her sobbing or mildly chiding the man for his behavior and the man feeling guilty about it.

There is a common trope in Indian Cinema wherein a man is frustrated because his wife is not able to consummate the marriage because of her immaturity. The sexual frustration thus produced, often results in the man forcing himself on her. This trope has been milked in films like “Anubhav” (1986), “Tan Badan” (1986), and more recently “Naughty at 40” (2013). In all these three films, the attempts are foiled by the girl creating even more frustration among the men, justifying their act of cheating on their partner later in the film.

The act of cheating rather than being vilified is seen as a narrative tool to make the female protagonist realize her own sexuality. This trope has been taken to another level in films like “Chittemma Mogudu” (1992) where the male protagonist ends up raping his wife after failing to consummate his marriage with her. This sexual act eventually leads to her becoming pregnant and realizing her sexuality transforming from a girl to a woman. Marital rape has often been justified if the woman is disinterested in consummating the relationship or doesn’t respond to the advances of the husband.

In “Majaal” (1987), the lawyer couple debates the legal aspect of the consummation of marriage and the man replies that “a man has the right to have sexual relations with his partner, and if the wife refuses, he has the right to rape her.” Even otherwise, women often end up as the victim of the sexual violence perpetuated by the men. In “Striker” (2010), the protagonist is frustrated over his personal and professional losses and is unable to take any nonsense from the girl and forces himself on her in retaliation to her verbosity. Similarly, in “Hum Tum” (2004), the male protagonist smooches the girl whom he barely knows, as he loses his patience after being defeated in a discussion.

The Stockholm Syndrome with the rapist is yet another significant trope in Indian cinema. The girl forgets her oppression when she realizes the larger purpose of the action of her rapist which implies that he is not “a bad man after all”. In the case of harsh historical narratives like the partition of India, women gradually learn to live with their perpetrators as they realize that after their abduction and assault, they belong to no one and nowhere.

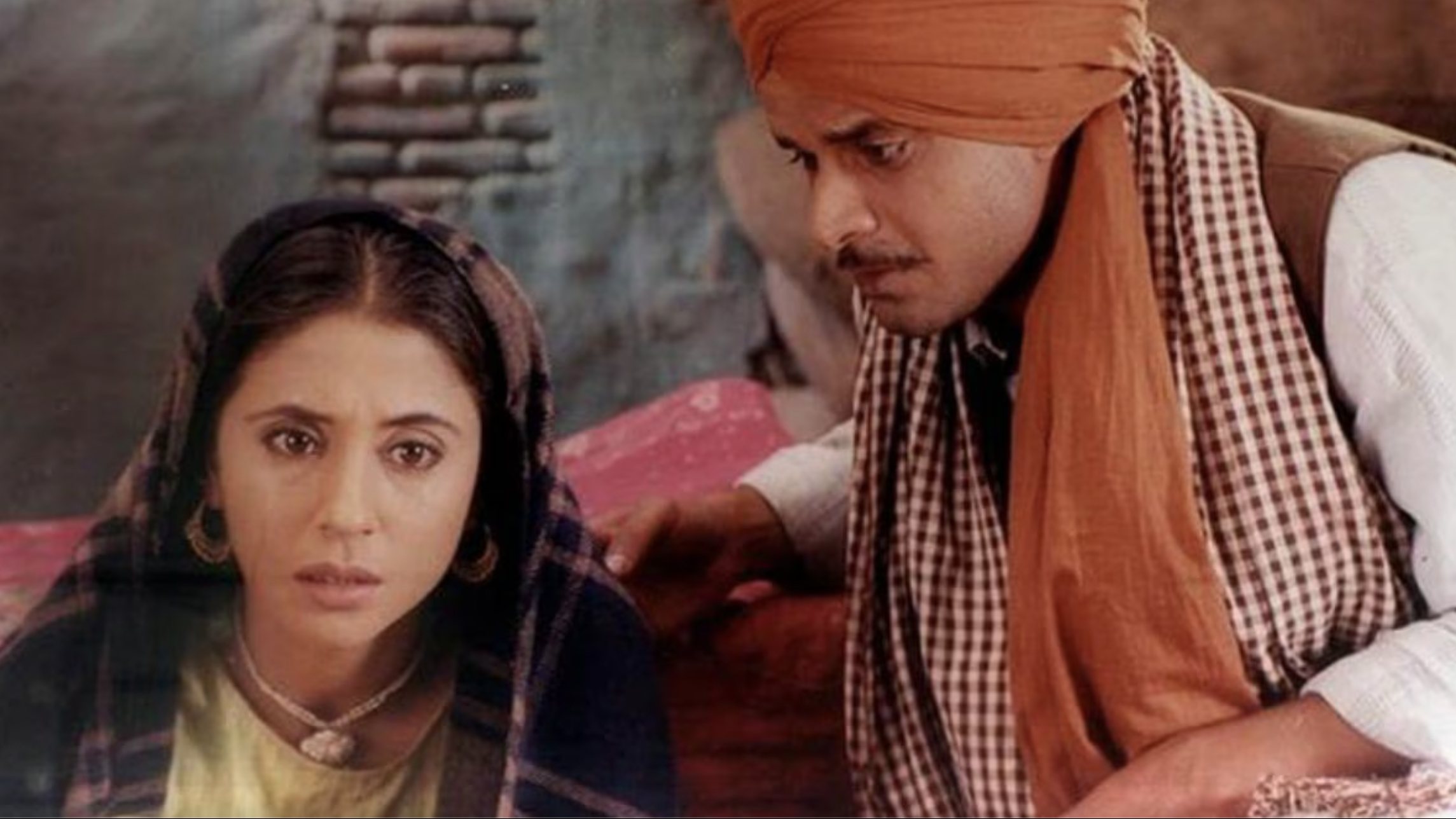

This aspect is reflected in films like “Pinjar” (2002) where the girl ends up choosing the man who abducts her and keeps her in his home forcefully having children with her. Even though the film does talk about the redemptive journey of the male protagonist and his attempts to reconcile her with her family, he is not punished for his act as the boundary between right and wrong, good and bad gets blurred in the wake of a tragedy like the Partition.

In “Hawalat” (1987), the male protagonist abducts the girl and hands her over to his bosses who sexually assault her multiple times. The protagonist realizes the intensity of her assault and in redemption, attempts to reconcile the girl with her brother. The film ends with the same rhetoric that is inserted into the mouths of the female protagonists, dictated by patriarchal dictates. The question asked is “Who will marry a raped girl?” and the answer comes from the perpetrator “I will!”. In “Raja ki Aayegi Baraat” this affirmation is forced by the Court, and in “Hawalaat,” this affirmation stems from the guilt of his involvement in the woman’s assault.

Similar guilt is explored in films like “Amar” (1954) and “Satyakam” (1969). In the former film, a well-to-do man, who is about to get married to a big family and has an active love interest, ends up raping a poor, tribal village girl on impulse, and the rest of the film traces his guilt to confide his act in public and in particular to his loved ones. The film ends with the union of the man with the tribal girl.

The consequences of such a union which is riddled with a sense of guilt have been explored in “Satyakam,” wherein the man marries a raped woman because he considers himself responsible for her assault as he failed to oppose the Zamindar who called her to his room. Even though he gets married to her, the union is based on a deontological premise based on the sense of duty towards the woman.

There are films where sexual assault is used as a legitimate way to kindle romance with the woman. This includes the male protagonists caressing, spanking, and groping the girl as a means to show the intensity of his love. In the films starring Jeetendra in the 80’s like Himmatwala (1983), Mawaali (1983), Maqsad (1984), Zakhmi Sher (1984) etc, the hero constantly spanks and gropes the girl as part of his attempt to woo her.

In Dil Se (1998), the male protagonist is head over heels in love with a girl who clearly shows her reluctance in having any romantic liaison with him. And this uncomfortable interaction leads to him forcefully kissing the girl to evoke emotions out of her! In Tere Naam (2003), the protagonist abducts the girl to show her his love, when she refuses to accept his advances. In Shootout at Wadala (2013), the male protagonist forces himself upon the girl to show that he still harbours the same love for her as earlier. The idea of romance that was perpetuated in the Hindi films often bordered around stalking and inappropriate behaviour on the part of the male protagonist, and the process continues till the proposal is not accepted by the girl!!

Another trope conveniently used to justify sexual assault is alcohol. This trope was used in “Himmat aur Mehnat,” “Shehzaade” (1989), “Nazrana” (1987), and “Badle ki Aag” (1982) among many such inane commercial potboilers. In “Shehzaade,” the man is called out for sexually assaulting a girl who is healing her wounds, while in “Nazrana,” an already married man gets enticed by a beautiful woman, and makes physical relations with her in an inebriated condition, only for the girl to bear the brunt of the unwanted pregnancy and extra-marital affair of the man, and end up dying in a pitiable condition. A similar thing happens in “Badle ki Aag,” where the protagonist, in his drunken state, imagines another girl as his beloved and ends up making physical relations with her, realizing his mistake much later, even though the film ends with his union with the girl who carries his child.

Conversely, if the girl is drunk, it becomes an opportunity for the male protagonist to take advantage of her lack of consent for sexual advances. In “Tum” (2004), the boy is enticed by a heavily drunk lady, who is older than him by many years, and ends up having sexual relations with her without her consent. In some cases, the drunk status of the man is used to incriminate him in sexual assault cases, and guilt trips him into paying money or marrying the girl. Such films include “Do Dilon ki Dastan” (1985), “Pyar ke Do Pal” (1986), “Pyar ke Kabil” (1987), etc. Even in such cases, there is always a way for the protagonist to circumvent the legal consequences of his act.

The discourse of sexual assault in Indian cinema requires a book-length analysis. What I have attempted here is to analyze certain trends and tropes prevalent in cinema that are used to legitimize sexual misconduct. I have focused primarily on Hindi cinema, but the scope of such research can very well be extended to cinemas in other regions of India as well.

![Lookback on Lumet: Fail-Safe [1964]](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/fail-safe_film-1600x900-c-default-768x432.jpg)