Salvador (1986) was Oliver Stone’s first good political cinema; radical in its intent and featuring a well-evolved visceral outlet to voice out his combative critique on Reagan-era foreign policy in Central America. His first two directorial outings – The Seizure (1974) & The Hand (1981) – were forgettable and awful films belonging to horror genre. Mr. Stone had better success rate with scriptwriting work. He won writing Oscar for Alan Parker’s Midnight Express (1978) which although quickly gained a cult status was condemned for its racist attitudes and over-dramatized, one-sided attack on Turkish penal system (Stone expressed regret, years after the film’s release when he visited Turkey). Oliver Stone also wrote the script for the gangster epic, Scarface (1983). But his political themes were watered down by director Brian de Palma’s extravagant visual style.

The year 1986 also saw the release of Oliver Stone’s war drama Platoon which won four Oscars, including the award for Best Director. However unlike the close experiences he had in Vietnam, Stone didn’t have much understanding about America’s role in Central America. The film-maker admits the knowledge of the region’s political turbulence in the late 1970s & 1980s was bestowed upon him by his friend and journalist Richard Boyle (who shares screenplay credits with Oliver Stone in ‘Salvador’). The result was an irregular character study of a redemption-seeking journalist and an episodic presentation of the Salvadoran tragedy, made possible by the CIA goons and barbaric military junta. Stone’s Salvador may lack the polish or visual profundity of Platoon or JFK (1991), yet this project gave him the space to hone his idiosyncratic shooting style.

With Salvador, Oliver Stone not only tackled a major political subject but also worked without the help of a major studio, mortgaging his house to get finance until a small-time British production company (Hemdale) bankrolled the project. The film had a very brief run in the theatres (in March 1986) and reached wider audience only through the video market and due to positive reviews of influential critics.

The subject Salvador dealt with couldn’t be more timely as the darker truths behind US government’s efforts to support ‘friendly’ regimes in Central and South America were then fervently discussed (the Iran-Contra Affair or Irangate was also a predominant poltical issue that plagued President Reagan’s second-term). Before Stone’s Salvador, there was another significant American political thriller titled Under Fire (1983) by Roger Spottiswoode. That film was set during the last days of corrupt regime in Nicaragua. Both the movies came close enough to question the morality and nature of US relationship with Central American dictatorships (Under Fire was of course comparatively subtle).

Related to Salvador: A Lookback at The Unofficial Oliver Stone US Presidents Trilogy

Salvador is set during the years 1980 and 1981 when US-backed, right-wing Salvadoran government employed death squads to kill at least 30,000 alleged dissidents. Between 1980 and 1992, a civil war wracked the small Central American nation, pitting the extreme right-wing government forces and left-wing guerillas Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN), an umbrella organization of the nation’s left-wing groups. The Reagan administration saw the Marxist guerillas as mere puppets of the Soviet Union, even though FMLN didn’t receive as much financial and military support from Soviet as the Salvadoran government received from US; nearly $1 billion since 1980.

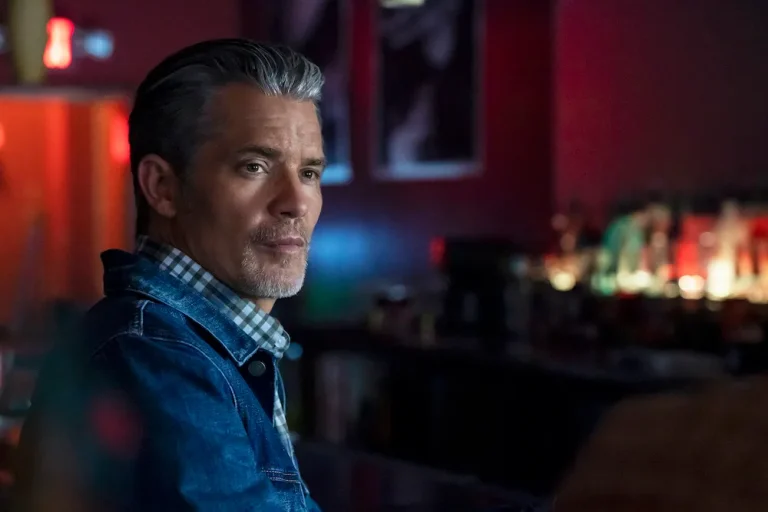

Oliver Stone views the conflict from the perspective of American photojournalist Richard Boyle (James Woods). Boyle isn’t exactly a hero material. He is an alcoholic, philanderer and has a penchant for exploiting people’s misery to sell images. When he hears news of escalating crisis in El Salvador he hopes it turns into another Vietnam situation. There’s not much regret in Boyle’s face when he learns his Italian girlfriend has left him with their infant son. He cons his frustrated, disk-jockey friend, Dr. Rock (James Belushi) out of some cash and even convinces him to take this trip with him to Central America.

Moreover, Boyle promises Rock that theirs will be an adventure filled with whores, booze, and drugs. Oliver Stone has remarked that Hunter S. Thompson and his brand of gonzo-journalism was a huge influence in shaping Boyle and Rock’s on-screen antics. Boyle is hinted to have had some success with his stint in Vietnam (he has even written a book on it), but he has becomes unreliable over the years.

Boyle’s repellant jokes about getting ‘the best pussy around the world’ are shockingly at odds with the brutalities going around them. Dr. Rock is just an ignorant, stoned guy, glad enough to spend $7 on prostitutes. But he flinches when he sees a college student getting a bullet in the head for not carrying ‘Cedulas’, a national identity document. Boyle is familiar with all this and he just hopes to renew his old contacts, inlcuding that of a military colonel pal and human-right activists. He craves for juicy combat shots and pictures of heavily injured children which can boost his prospects better. Boyle meets a colleague named John Cassady (John Savage) and reunites with his Salvadoran lover Maria (Elpidia Carrillo), a peasant girl with two little kids. As the domestic crisis blows into a violent civil war, Boyle’s hibernating humanity slowly wakes up.

In Salvador, Oliver Stone equates Boyle’s quest for redemption with his relationship with Maria. There’s a beautifully improvised scene of James Woods’ Boyle (shot in medium close-up) taking confession in the Church, hoping to extricate himself from sin. The photojournalist’s personal involvment in the Salvador conflict only deepens when he learns about the brutal killing and rape of his American aid-worker friend. Eventually, Stone turns Boyle into a conduit to convey as well as condemn the global ignorance on the crimes of American & US-aided aggressors.

Also Read: The Parallax View [1974] Review – Deceptions Hidden in Plain Sight

Writer/director Oliver Stone’s treatment of the vicious conflict alongside Richard Boyle’s quest for redemption ostensibly hints at the dual meaning of the film’s title. It not only refers to the name of the little, war-torn Central American country, but also means ‘savior’ in Spanish. Boyle isn’t exactly turned into a conventional Hollywood-style ‘white-savior’ (for eg, Di Caprio’s self-sacrificing Rhodesian mercenary character in Blood Diamond). Perhaps due to James Woods’ brilliantly restrained portrayal of Boyle or may be due to Stone’s three-dimensional writing. Boyle’s transformation to an truly empathetic individual from being a narcissistic asshole largely looks convincing. Nevertheless, Stone’s writing falters whenever he tries to bluntly blend Boyle’s personal investment with the Salvadoran conflict.

There’s a disturbingly effective early scene in Salvador when Boyle and Cassady visits the death squad’s body-dumping grounds to get few shots of ‘human suffering’. The distant manner exhibited by the two photojournalists and the way Boyle uses this information to further his cause breaks our idealized notions of war correspondents. But director Stone employs the familiar heightened dramatic tactics to makes us root for the now-changed protagonist. Boyle’s furious polemic with a pair of despicable CIA observers, Major Max’s excessively expository conference with the army thugs, the overdramatic closure to Cassady’s character, and Boyle’s last-minute escapes from the clutches of death-squad only serves to dilute the film’s incendiary tone (referred as ‘Stone excess’ or ‘sledgehammer-subtlety’, the term has followed the director througout his career).

Overall, Salvador (122 minutes) is compulsively watchable for its audacious, insightful subject matter, and for James Woods’ high-energy performance.

★★★½

Salvador Trailer

Salvador (1986) Links: IMDb, Rotten Tomatoes

![Cherry [2022] ‘Tribeca’ Review: An Uplifting and Important Coming-of-Age Story](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Cherry-2022-768x432.png)