Yoshimitsu Moritu’s The Family Game (Kazoku gemu, 1983) – based on Yohei Honma’s novel- is an absurdist satire on the Japanese middle-class. It’s full of instantly recognizable characters living in a schematically rigid social and familial atmosphere. The father Mr. Numata (Juzo Itami) is a salaryman who is physically and emotionally absent. Mrs. Numata (Saori Yuki) is a glorified domestic help who is bored by her housework and emotionally drained by taking care of her two teenage sons. Shinichi (Junichi Tsujita), the elder son, is in high school and his rank has to be good enough to get into a prestigious national university. Shigeyuki (Ichirota Miyakawa), the allegedly hopeless younger son, hen-pecked by his mom and dad to move up in the ranks and get into a better high school. The parents express their exertion, the children rebel. The four are part of this tiring game.

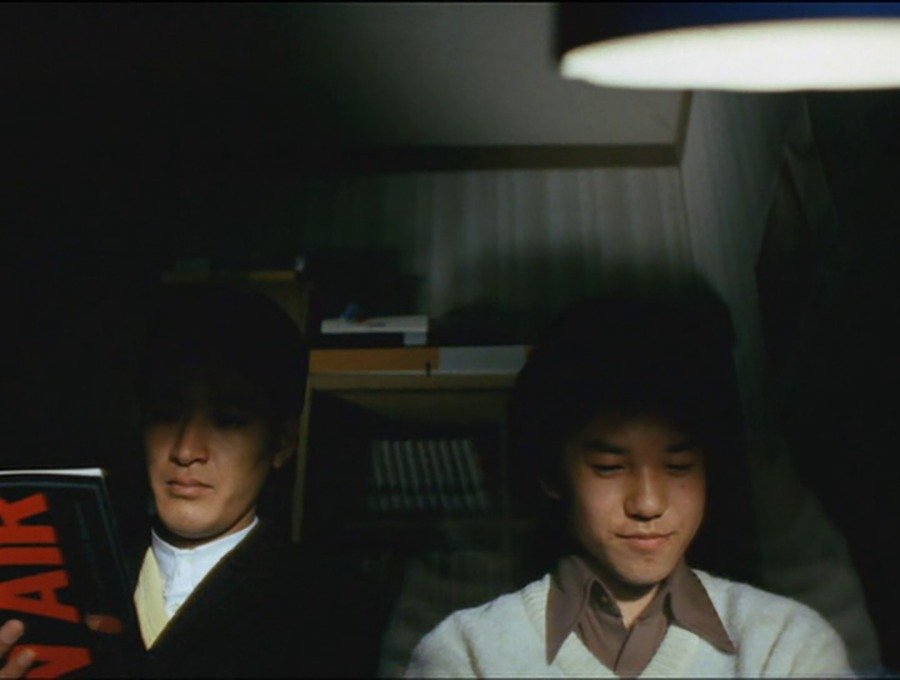

The semblance of domestic placidity in the Numata family is breached with the arrival of a tutor, Mr. Yoshimoto (Yusaku Matsuda). Though he seems to be polite, it becomes clear that he has nothing but contempt for this family, limiting itself to play the preordained role. Mr. Numata promises to reward Yoshimoto with a bonus if he could boost Shigeyuki’s ranks. Shigeyuki, the black sheep, doesn’t want to play the game. He finds pleasure in annoying his bullies, including the tutor who slaps him around.

There’s also something strange in tutor Yoshimoto’s behavior. He says Shigeyuki has a ‘cute face’ and is often seen intruding upon the family’s space. But Yoshimoto isn’t outright creepy. He simply takes the parental duties from the inept Numatas. After delivering a slap to assert some masculine ‘discipline’, Yoshimoto also offers some valuable fighting tips to Shigeyuki to face his bullies. Despite the tutor’s irreverence, Shigeyuki’s grades get better, and he is almost within the reach of getting admission to a good high school.

Related to The Family Game: The Funeral [1984] Review – Wickedly Satirical and Rapturously Inventive Dramedy

The repetition and perfectly narrow, geometric compositions in The Family Game reminded me of Yorgos Lanthimos’ Dogtooth (2009) although Moritu’s film is funnier and less creepy. Nothing dramatic comes out of this narrative set-up. Shigeyuki achieves what his parents wanted him to achieve without much fuss, thanks to the tutor. But the narrative isn’t absolutely directionless. Its pleasure lies in absorbing the supremely satiable mise en scene, which deftly parodies the pathetic bourgeois tendencies of Japan’s reasonably affluent new middle-class of the 80s. The very narrow Western-style dining table where the family sits on the only one side, the claustrophobic small apartment in the high-rise building facing Tokyo Bay, and the industrial landscape sharply define the narrative’s environment.

Morita opens the film by showing us each of the family member’s peculiar way of eating. They all have breakfast separately on the narrow dining table. The Numatas’ small apartment is furnished with modern electric conveniences An African wall painting is supposed to express their ‘cultural refinement’. More interesting is the manner Morita uses compartmentalized shots to throw us off balance from grasping the landscape as well as the characters. For instance, when Shinichi goes to meet his crush Mieko – a classmate – the strangeness of her family home is evident. She seems to be living behind a departmental store, and her own room is accessible only through an elevator. The interpretation of space or landscape through these compartmentalized shots adds to the character’s general sense of isolation.

Though Morita’s screenplay is witty and engaging enough, the spatial and narrative idiosyncrasies of The Family Game could be fully savored when watched with a contemplative mindset (and in the re-watches). Morita and novelist Honma’s intention is to unmask the fakery behind familial structure which forces predefined roles on individuals. To showcase how the rote behavioral patterns can make us approach life devoid of any genuine feelings. Moreover, through this satire of Numatas, the film-maker strives to highlight the worst aspects of Japan’s march towards economic modernism. The brilliance of Morita’s The Family Game, however, lies in the way he wages the sociocultural assault by employing complex visual compositions. I wasn’t able to perceive some of the visual patterns or visual gags in the first-time watch. That may make the film sound like a strict formal adventure that elicits intellectual curiosity, but there’s ample emotional emphasis too.

Shinichi’s interest in astronomy insists on his desire to escape the rubble of high-rise buildings and industrial landscape. He initially likes playing the ‘obedient son’, but when he sees his younger brother’s companionship of sorts with tutor Yoshimoto, his longing is evident. It pushes him to seek Mieko but soon finds out that there’s no joy in it. His uncertainty over becoming just another cog in the system causes more emotional agitation. Also beneath Mr. and Mrs. Numata’s comically infantile behavior, Morita depicts their utter inability to relate to their children. Except for rare moments that spell out the family’s togetherness – for eg., when Shinichi and mom listen to a song from ‘My Fair Lady’ – the parents have totally lost themselves to the conventionalities of daily life.

Also Read: Courier (1986) Review – A Poignant Coming-of-Age Drama Set in the Twilight of Soviet Union

The most memorable comic set-piece of The Family Game is the unbroken six-minute dinner scene that’s supposed to celebrate Shigeyuki’s acceptance into a good high school, but leads to total anarchy and eventually to an upended dining table. Tutor Yoshimoto sits in the middle between the parents and children, and all of them sitting on one side of the table with no elbow room. Initially, Yoshimoto quietly breaches Japanese etiquette, first freely pouring wine on his glass. Later, he starts dumping spaghetti on others’ plates while also splashing some more wine. Before going out, he delivers a knockout punch to each of the Numatas –literally expressing what he thinks about their bourgeois sensibilities – and takes his ferry across the Tokyo Bay.

Overall, The Family Game (107 minutes) provides a strong critique on the fiercely competitive, modern familial, and socioeconomic structure. Its profound visual arrangement and layers encourage multiple readings of the narrative and its context.

★★★★

Trailer

The Family Game (1983) Links: IMDb, Letterboxd

![Boogie [2021] Review: Pure Visual Hip-Hop](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/boogie-768x432.jpg)

![United 93 [2006]: “Real World Situation !”](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/United-93-1-768x373.jpg)