The Declaration and Alienation of Ariyippu (2022): The migrant experience is an indomitable part of Kerala’s social milieu. With numerous seafarer routes, the gulf connection, and a candor sensibility eager to explore international cultures and lifestyles, I would venture to go beyond the popular phrase “you will find a Malayalee in every corner of the world” and state that “you will find every corner of the world in a Malayalee”. Of course, these Malayalees are hybridized subjects who have spent a long time away from their homeland, adapting new cultural ‘beingness’ but retaining their Malayaliness, nonetheless. When representing these migrant experiences on the silver screen, the “gulfukaran”, for example, has been predominantly romanticized as an individual living a successful and desirable life. However, beyond being characterized as economically well-off or fashionable, the silver screen has allotted limited space to explore other attributes along the lines of individual struggles or sacrifices that also characterize the migrant experience.

New Generation Malayalam directors have explored the anxiety of being away from the homeland in films such as Manjadikkuru (2008), Pathemari (2015), Take Off (2017), Koode (2018), etc. It is along this impressive line-up of tales on migratory subjects that Mahesh Narayanan’s Ariyippu or Declaration (2022) aligns itself as it became the first Malayalam film to compete for the prestigious Golden Leopard at the Locarno International Film Festival in 2022 and the first Indian film in 17 years to be featured at the festival. So, what qualified a regional film like Ariyippu for an A-list international film festival like Locarno with its culturally different sensibility and later, the BFI London Film Festival?

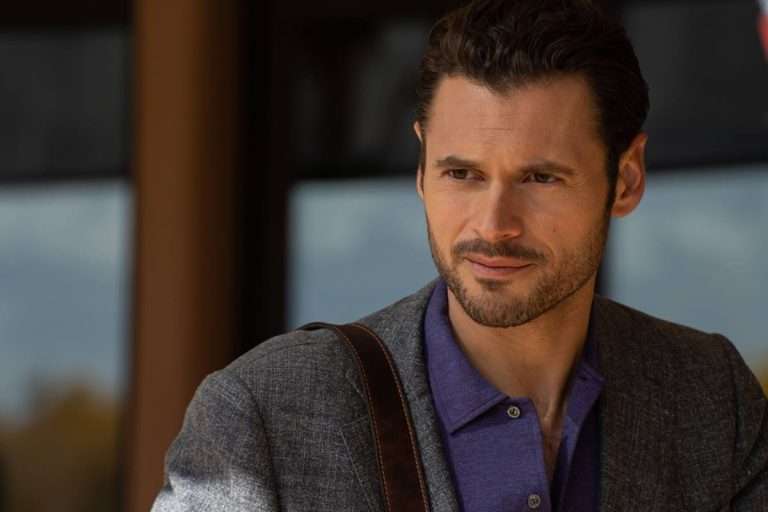

Ariyippu (2022) documents the struggles of Hareesh (Kunchako Boban) and Reshmi (Divya Prabha), as migrant workers in a rubber glove production factory in Delhi NCR. They toil away, distant from their Malayalee homelands, in hopes that Delhi may present easier opportunities to secure visas to travel abroad for a better life. Unexpected events lead the protagonist couple down a road of shame and humiliation which ultimately reveal the exploitative working conditions and defective manufacturing procedures within the rubber glove factory. The film also foregrounds a narrative on marital tensions and misogynistic power dynamics.

At the core of Narayanan’s narrative is the alienating experience of the Malayalee couple in the urban milieu of Delhi. Malayalam cinema has often capitalized on the agrarian green pasturelands and geographical diversity of the Kerala homeland to enhance cinematographic compositions and invigorating visual imagery for semiotic cultural conveyance for audiences. Contrary to this, Narayanan presents a dull monotonous Delhi-NCR with its chilling (literally and figuratively) and mysterious thick winter smog. With its polarising temperatures, dense bustling population, atrocious pollution, stark income inequality, religious tensions, and migrant population, Delhi has often been a hub of neo-liberal cultural alienation. This neoliberal capitalist world with its mechanical, emotionally devoid functioning is personified through Sanu Varghese’s capturing of the glove production machinery in a manner that is both cold and hypnotic. Added to this, the presentation of social distancing due to the Covid-19 pandemic furthers the alienated depiction of Delhi, likening it to a post-apocalyptic world. This characterization also foregrounds an everyman-for-himself sensibility that is often associated with the claustrophobic and cramped subjective experience of Delhi.

The relationships characters share are conditional and based on gains. Hareesh has to provide alcohol to a fellow Malayalee travel agent in order to arrange his visa. The commonality of being residents of the homeland is fruitless in the unforgiving pandemic-stricken Delhi. On the circulation of a controversial video supposedly including Hareesh and Reshmi, for which the travel agent is partially responsible, the agent assumes no accountability and in fact, tries to distance himself from the controversy. At the same time, another intriguing decision of Narayanan’s is to show Hareesh’s companionship with another Malayalee, Ismail. In a land that has recently seen violent clashes on grounds of religion, particularly between Hindus and Muslims, is transfixing a Malayalee companionship of the same communities within the volatile space of Delhi a larger call to recognizing humanity over religious fanaticism? Is it the common denominator of a working-class factory laborer that bonds Hareesh and Ismail?

Beyond the relationships based on the commonality of the homeland, Narayanan’s placement of the narrative in the faraway land of Delhi also allows for interesting dialogue between the geographically polar populations of the country. For example, in the conversations between Hareesh and the police inspector he files his complaint, there is visible confusion and misunderstanding in their interaction. Narayanan presents the normalized practice of bribing in Delhi and at one point, the Police inspector mocks Hareesh about how migrant laborers used to travel to Kerala for work and that it is out of place to see a Keralite come to Delhi for work. The unfamiliarity the inspector shows Hareesh and the emotionless and unempathetic health checks on Reshmi is indicative of an ‘othering’ that the non-Hindi speaking population is subjected to. All these further add to the alienated experience of the Malayalee couple and with that, the audience as well.

Women ultimately have to fix the mess made by men. The men in Ariyippu (2022) are privileged by their gender to ignore and sometimes silence any threat that faces them. Hareesh engages in domestic abuse over a misunderstanding and at one point even sexually forces himself onto Reshmi, the factory manager allows used glow to be reused and low-quality gloved to be manufactured and shipped to reduce the production cost, and the factory owner is suggested to have engaged in a sex scandal with a previous employee and tries to bribe the survivor into silence. On the other side, Reshmi is made to be the scapegoat whose bodily autonomy and opinions are side-lined by Hareesh to prove his innocence and clarify his consciousness. Similarly, the senior inspection officer has to collect evidence in secret to produce proof of the factory manager. When she presents her concerns about the faulty gloves that the factory produces and the degrading quality of the latex used, she is met with ignorance from the senior line workers and factory manager (who are all men) who further go on to criticize her eyesight and age. The factory owner’s wife is shown to be responsible for taking active steps to provide for the survivor of the sex scandal and silence any dissent aimed at her husband.

Hareesh, specifically, initially comes across as an honest hardworking man but cracks under pressure, shame, and doubt, ultimately unmasking his misogynistic behaviors. Narayanan presents a nuanced characterization of Hareesh’s being that doesn’t tread on monolithic templates of evil in order to prevent reductionist reading of the text as an ‘Us vs Them’ binary and very much reinforces that ‘Hareesh’ is a regular hard working individual like you or I.

Most importantly, the film foregrounds a narrative of sisterhood. Reshmi’s friend, Sujaya, provides her asylum after she was abused by Hareesh. The senior inspections office is like an elder sister to Reshmi. She colludes with her to topple the corrupt factory management and shows concern for Reshmi when she sees her bruised after the abuse by Hareesh. Reshmi further extends this sisterly affection as she stands for the woman who lost her life after the sex scandal involving the factory and refuses to take the factory’s offer of a free visa and relocation to Malaysia. Reshmi, unlike Hareesh, is able to create bonds in the alienating land of Delhi and even strives to uphold the dignity of the deceased. Thus, beyond the alienation that Narayanan prefaces with the geographical separation, the film champions a need for sisterhood and solidarity beyond borders, spatially or linguistically.

Ariyippu (2022) may be the last of the ‘pandemic productions’ from Malayalam cinema that have focused on specific attributes like handheld cameras, interior shots with dulled lighting, psychological torment, and constructing and deconstructing bonds. The universal experience of the Covid 19 pandemic has allowed for more relatable productions which have allowed for a wider audience even as the content of films is regionally contained. The global success of Joji (2021) is testimony to this. Therefore, it is no surprise that Aryippu, with its coupling of the pandemic setting and presentation of nuanced human emotions which skew benign boundaries of good and bad with universal realities of misogyny and sexism, has garnered the international attention it has received.

![Parasite (Gisaengchung) [2019] Review – A blood sucking drama on class divide](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Parasite-highonfilms2-768x321.jpg)