The development of humanism during the Renaissance was meant to amplify the importance of the human being through rational arguments, against the primacy of divine beings. It was, in essence, meant to strike out religious dogmatism that was widespread in medieval Europe. Yet, instead of turning into the humanitarian quality it aimed to become during the Renaissance, the introduction to various markedly different cultures in the East during the age of imperialism turned humanism into a mark of culture and civility.

As Europeans followed this belief, they were the civilized lot while those not exposed to it were not. This is indeed the touchstone of colonialism, the spread of Western values as altruism borne out of the Christian doctrine of compassion and generosity to those in need of it. In this context, the purpose of colonialism became that of exposing the unenlightened East to these values. The barbarity and lack of progress that this part of the world was presumed to possess became a project for the West, that of enlightening them against it.

Related Read to Ankur (1974): The 10 Best Shyam Benegal Movies

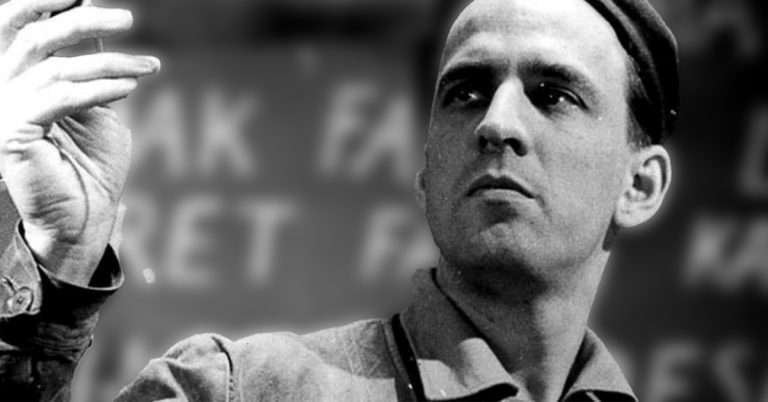

This colonial project, the desire to be a flagbearer of values that are yet to be learnt by natives, plays into the concerns of Shyam Benegal’s debut feature, ‘Ankur’. It seeks to depict how obstacles to the march of history, even if they present themselves as being beneficial, cannot in any fashion, catalyze it. What Benegal uses to arrive at this conclusion concerns itself with questioning Western liberalism and its belief in itself to be an uplifting agent.

In the film, it is the urban-educated Surya who personifies the Western way of thinking. His father on the other hand is a stereotype of the tyrannical conservative who controls every aspect of his offspring’s life. He is a landowner who wishes his son to inherit his empire as a worthy administrator. The collision that is on course then, is between the conservative feudal lord and Surya himself, whose apparent interest in education means he sees little value in such practices. The liberal young fellow, coerced into a marriage he does not wish for in the least and encumbered with duties he has no interest in, takes it upon himself to be a deliberate outcast amongst the backward villagers. So he begins to make changes to his lifestyle in accordance with what he deems right, even if it is rebuked by the villagers.

To look at this as a conflict between tradition and modernity is natural and Benegal keeps us invested in the same. The opening scene of the film sets the contingency towards which the plot has to progress, that of Lakshmi’s desire for a child. One can easily determine the fate of Lakshmi then, from Surya’s prolonged gaze when she is cleaning his house. And the inevitable is accelerated by the opportunity Surya finds in getting rid of Kishtayya, Lakshmi’s deaf-mute husband. When caught stealing the palm wine, Surya instantly calls for Kishtayya to be subjected to a traditional, humiliating punishment. The abrasive Surya, who has no issue in proclaiming his disregard for the caste system seems to be perfectly fine with subjecting the innocuous Kishtayya to such a cruel practice.

It’s here that the broadness of the conflict is both narrowed and destroyed. It is narrowed in that it continues to exist in Surya’s continued indifference to his growing disrepute through his relationship with Lakshmi. Yet the fact that he might have any actual sympathy for the plight of the downtrodden is visibly shaken by his pursuit of a vendetta against Kishtayya as his sexual competition in possessing Lakshmi.

Related Read to Ankur (1974): 10 Uplifting World Cinema Movies for the Family

Benegal brings in sexual desire as the determining agent of this break and also as the differentiator in the conflict. Surya, in his amorous pursuit, is like all swaggering young lovers. His male perspective makes him blind to the consequences his desire holds, social or personal. Once Lakshmi’s pregnancy from their relationship surfaces, the liberal guise is instantly shed. He becomes timid and afraid. Unlike his father who provided shelter and land to the consequence of his philandering, he wants to hush up the whole affair. The bravado of social subversion ends and we are faced with a weakling whose guilt and paranoia turns him into acting not unlike slave owners as he brutally whips Kishtayya out of a fear of the exposure of his exploits. Despite the antiquated notions that Surya’s father holds on to, he is consistent in his beliefs as he treats his illegitimate child and mistress honourably, instead of shedding all responsibility, like Surya.

The defeat of this secularized liberal is indeed a defeat of a colonial mindset. Surya sees himself as a saviour. He doesn’t understand the complexities of land administration and as mentioned, seeks to use his education in doing some greater social good, of uplifting the lives of the oppressed. One can hardly question the intentions as he tries to radically destroy the feudal caste system by exposing it to Western ideas of democracy and equality. It is the pursuit of this purpose where his failure lies, not in the intentions themselves.

Related Read to Ankur (1974): Welcome To Sajjanpur and the “Quirky Heartland Comedy” Trope

The most prominent aspect of oppression in the film is the treatment of women. The relegation of women, even those not from lower castes, is rampant in the village as we see them always engaged in domestic work with an expected degree of servility. Yet, through this systematic degradation, one can see how the women themselves are the force behind their own emancipation. Rajamma is extremely boisterous in her appeal against her impotent husband and the commodified life she leads amongst his brothers. Lakshmi has no qualms with bringing a child up without any male assistance, be that of Kishtayya or Surya. The wife of one of the villagers, who in his drunken stupor wagered her while gambling is sternly admonished by her publicly for this insult he puts her through. Even Saru is vehement in her appeals against the clandestine bigamy that Surya might be practicing in their household.

This rebellious undercurrent by the women of the village becomes the actual object which Surya’s liberalism is conflicted against. Surya, even if he is stripped of his personal motives, embodies a radical change that seeks to destroy an established patriarchal, casteist system overnight. The hegemony to which the women and lower castes are subjected to is to him, the equivalent of a colonial project where he can express his own newfangled ideas.

Yet, akin to the imperialist doctrine of colonisers being the emissaries of progress, Surya’s failure is in his own self-interest. While he may have had some semblance of a desire to really change things for the better, in the end, it was little more than a hobby to keep his actual desire of doing his B.A., away from his prying father’s eyes. And eventually, this hobby turns into a facilitator for his sexual desire towards Lakshmi. The defeat of such progressive thinking then becomes a matter of time as the idea of fathering a child with Lakshmi and officially declaring their union petrifies him of the consequences. And in this, he fails to see how the systemic subjugation is what makes these people wage their own battles against it in search of their liberation, without the need for outside intervention.

Benegal presents to us, through this film, the transience of such charitability. Much like how colonial self-interest was defeated by indigenous interests that outlived their veneer of magnanimity, Surya’s lustful desire for Lakshmi is outlived by her own genuine desire for a child. This force of desire of hers is so intrinsic to her that in ensuring the birth and rearing of this child, she will become a far more potent rebellion against casteism than Surya ever could be.

Related Read to Ankur (1974): The 5 Best Gautham Menon Movies

This faith in the progress of history, as a stream that ebbs and flows and eventually reaches its destination is where Benegal’s voice against the likes of Surya becomes most audible. There is no central ‘event’ in Ankur (1974) that announces itself as the culmination of its themes. Instead, much like the undercurrent of rebellion that exists amongst the women of the village, the theme presents itself throughout the film in a muted or vocal fashion, depending on the scene. What the appearance of Surya’s revolutionary fervour does therefore, is not facilitate this rebellion but instead, belittle the emancipatory aspirations in practice by seeing itself as being sympathetic to a horrifying experience that cannot be understood without living it.

![Gabbeh [1996] Analysis: Glimpses into a lyrical divinity](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Gabbeh-1996-768x509.jpg)