Spike Lee has proved himself to be one of the greatest New York filmmakers of his generation, excelling in style, substance, and storytelling. His films approached the intricacies of prejudice, relationships, cultural influence, and the racial structure of America, and did so in a very up-front manner that was heavily stylised, yet entirely life-like. This series brings to light some of the works he directed (and wrote and produced and starred in) in his prolific career, each of which was billed as: A Spike Lee Joint.

Read previous entries for: Jungle Fever, Summer of Sam, She’s Gotta Have It, BlacKkKlansman

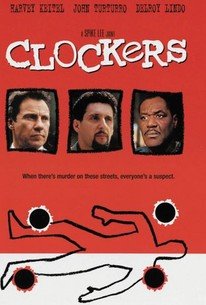

Set in the not-too-glamorous home of a housing project, Lee sets his sights on street-level drug dealers (aka clockers), namely Strike (Meiki Pfifer), a young gangster who embodies an equal share of impressionability and willingness to escape his limited setting. But his anxiety-ridden life is dominated by two ends: Rodney (Delroy Lindo), the king drug dealer of his quarters, and Detective Rocco (Harvey Keitel) who tries diligently and assertively to break into Strike’s conscience.

Lee likes to begin his films with some truly memorable opening title sequences to set the tone and kick off his stories, and the one for Clockers singes in the mind for how harrowing it is. We see an array of dead young black men, riddled with evident bullet wounds and photographed with a forensic-like lighting that reveals all the grisly details of their deaths. After seeing all these murdered men, the film centres on only one: rival drug dealer Darryl (Steve White). Clockers shows the events leading up to his murder, but omits the death scene itself to add a layer of mystery.

Two men are suspects: Strike, who we see being ordered by Rodney to kill him, and Strike’s brother Victor (Isaiah Washington), who we see being goaded by Strike to commit the murder for him. The mystery is whether Strike pulled off his deed or if his brother saved him jail-time, though what Clockers truly focuses on are the repercussions of this death that turn this hostile community both on to each other and with each other. As the story progresses, and more strands and characters get introduced, Lee’s portrayal of this community of clockers and cops becomes more palpable, particularly for Strike who has the screws tightened on his ever-troubling predicament.

The detachment of yet another dead clocker, as well as the pursuit of the justice of this anonymous black man, is at the heart of the film and especially the heart of Rocco. He isn’t an entirely heart-on-sleeve sympathetic cop, particularly as he cracks jokes while investigating the murder scene, but it is to assuage the pressures and hopelessness that pervades his work. Yet the situation between Strike and his brother unveils a strong appetite for truth and justice within him. At the film’s end, Strike even asks him why he cares so much about this particular dead black man, given all the dead black men he’s seen in his work, but Rocco doesn’t respond with a straight answer.

Clockers is as wildly stylish and as wholly captivating as Lee’s other films, but unlike his other films that portray struggling black communities like Do the Right Thing, there’s a deep sombre sense in Clockers as it shows a glimmer of hope in a community that is riddled with hopelessness. Strike claims his life as a clocker makes him sick to his stomach (though his serious illness is actually exacerbated by the chocolate milk he drinks) and this makes him feel all the more willing to escape his environment, yet also feel more confined to it as well.

The amount of empathetic attention to both crooks and cops in this tight-knit community make this feel like the suitable precursor to The Wire, though more wildly cinematic in that Spike Lee fashion. It feels like one of the more serious Spike Lee joints, taking a serious look at these kinds of communities.

![JFK [1991] Review: A Riveting Account of an Interesting Conspiracy Theory](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/jfk-screenshot-1-768x320.jpg)

![Causeway [2022] Review – Jennifer Lawrence steers this moving but slight PTSD drama with an understated performance](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Causeway-2022-Movie-Review-768x415.jpg)

![Ae Dil Hai Mushkil [2016] : Plastic Romance](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/adhm-story_647_092316082641.jpg)

![The Brittle Thread [2021]: ‘Tokyo International Film Festival’ Review – A Searing Critique Of India’s Religious Divide And Majoritarianism](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/The-Brittle-Thread-2021-highonfilms-768x432.jpg)