Spike Lee has proved himself to be one of the greatest New York filmmakers of his generation, excelling in style, substance, and storytelling. His films approached the intricacies of prejudice, relationships, cultural influence, and the racial structure of America, and did so in a very up-front manner that was heavily stylised, yet entirely life-like. This series brings to light some of the works he directed (and wrote and produced and starred in) in his prolific career, each of which was billed as: A Spike Lee Joint.

At the end of the millennium, and a decade after Spike Lee’s break-out hit Do the Right Thing (1989), this master director of style, story, and substance continued with his incredibly probing and incredibly entertaining examinations on specific New York cultures within a specific time, getting the most out of the individuals that resided in these colourful settings.

At the end of the millennium, and a decade after Spike Lee’s break-out hit Do the Right Thing (1989), this master director of style, story, and substance continued with his incredibly probing and incredibly entertaining examinations on specific New York cultures within a specific time, getting the most out of the individuals that resided in these colourful settings.

Likewise to Jungle Fever (1991), Lee presents another small story that fills out a lengthy run-time (142 minutes) as he takes his time introducing each character, their ambitions, their flaws, their tensions and relations with each other, and spends as much time examining each of the various sub-cultures as if they were their own characters as well.

Similarly to Zodiac (2007), released eight years later, Summer of Sam uses the well-known story of a real-life serial killer to inspect the culture this individual resided in. Just like Zodiac, the culture of its era (the Bronx in 1977) is unpacked, with its various sub-cultures merging, melding, and clashing.

What makes Lee one of the great American filmmakers of the ‘90s is that, very much like Martin Scorsese, he had a firm directorial handle on each and every aspect of the (rather wild) filmmaking. With each of his films, but particularly this one, Lee concocts a dizzying barrage of sweeping camerawork, long takes moving between locations, montage edits, slomo, stylistic non-diegetic lighting, and plenty of crane camerawork for simple on-street conversation so he can crowd the frame with the characters and the streets they populate.

Vinnie (John Leguizamo) plays the central character of this ensemble. He has the most thematic relation to the Son of Sam killer – when one of his infidelity episodes occurs right next to one of Son of Sam’s killings, his feels not only a deep existential fear, but a similarly pressured anxiety about his cheating, which would wreck his normality in life if his wife (Mira Sorvino) found out. It’s his normality, like his structured romance and steady job, that sets him apart from his dead-beat friends who stand around at a literal dead-end all day, dealing drugs and using hate and paranoia as a main recreation.

This paranoia is instigated by the Son of Sam murders – this killer, David Berkowitz (Michael Badalucco), is glimpsed at occasionally throughout the film, whose isolated and contained living in his apartment can’t stop the evils of New York City (represented by a neighbouring dog’s continuous barking) invading his lifestyle, no matter how much he tries to lock himself away from it all. A dog’s barking is present in each murder scene, though the barking may as well be 1970s New York’s historically high crime rate, its rampant drug use, its lack of garbage removal stinking up the streets, its soaring heat, and its lootings and riots and chaos on the streets in this particularly tumultuous time for the Big Apple.

This paranoia is exacerbated by the media, whose fascination with serial killers during this time in America is similar to their current fascination with spree shootings, as well as fringe extremist groups. With all New Yorkers getting caught up in serial killer hysteria, which will less likely kill them than heart disease or a car crash, they develop a mob mentality that creates a number of incorrect suspects, such as a hippy Vet taxi driver and a priest, whose useless efforts to curb the killings only creates more hostility and pandemonium for the community. The news, in cahoots with the police, offer ridiculous ways to avoid being killed by the Son of Sam, based on nonsensical statistics, such as dying your hair blonde because the killer seems to often only kill brunettes.

All of the tight-knit paranoia and cross-culture prejudice eventually culminate is a stunning final sequence that can be properly referred to as Scorsese-ian. Lee effectively cuts between the victorious capture of the actual killer with the Italian friends’ own entitled and violent sense of misguided vigilantism, all perfectly set to the tune of ‘Won’t Get Fooled Again’ by The Who, which proves how close music is to movies in Lee’s mind as he perfectly edits all the right exploding emotions of the song with these two juxtaposing storylines that amplifies the anguished irony of the sequence (Lee also uses The Who’s ‘Baba O’Riley’ to as excellent an effect for a mid-film montage, showing the passage of time as the culture of fear creeps up and starts to consume the characters).

A sequence like this can leave a viewer delirious and film-drunk, and it’s followed up with another extraordinary, though more low-key half-doco scene of Jimmy Breslin, who book-ends the film, explaining how the Son of Sam got caught, the repercussions of the blackout, the Yankees’ ’77 win, and a fairly humorously quiet aside at Elvis “the king of black music” Presley’s death – Lee implements his new-found documentary skills to cut together this varying footage with the same precise editing skills of his narrative work.

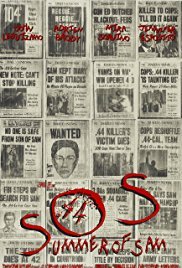

Given that a lot of the film’s promotional artwork, like the poster and DVD cover, displayed nothing but a collage of newspaper front pages, it accentuates the underlying impact the media has in (willingly or inadvertently) goading a generation of prejudice and vigilantism. It’s the sort of subdued topic in this film that seems even more relevant in 2018 than in 1999 or 1977, where social media can turn any misguided and unknowledgeable person into a rousing and magnetic cog in injudicious activism. I personally hope Lee has remained critical of this kind of media influence, rather than succumbed to mainstream media’s historically high level of moral manipulation it currently perpetuates.

Summer of Sam has never received the praise of other certain quality Lee films, like Do the Right Thing, Malcolm X (1992), and 25th Hour (2002) – even his upcoming BlacKkKlansman (2018) has already accumulated even more praise than this film. According to Jackson Arn of Senses of Cinema, its 1999 release was met with vapid criticisms because of its profanity and violence, as well as it generally being overshadowed that year by the works of emerging directors like David Fincher, Paul Thomas Anderson, Sofia Coppola, and David O. Russell.

This was also the first Spike Lee film to not feature any black leads, instead opting for white Italians (as well as white music), and it’s also one of the few of his films to not explicitly bring race to the forefront. There is plenty of the sort of prejudice you’d find in racism, though instead it comes from the fear of different cultures, which were emerging and clashing throughout the ‘60s and into even more turbulent times in the ‘70s. This communal mistrust was started by the city’s desolation, the personal issues that arose with the age of hard drugs and free love, the multiple different sub-cultures, the tabloid newspaper that clutched onto everyone’s minds, and a killer who did more harm than he even intended. Lee captured all this in a swift 142 minutes and this is just another one of his films that needs reappraisal as his award-winning BlacKkKlansman is released later this year.

![Olla [2019] Short Film Review : Women Choosing Vitality Over Victimhood](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Olla-2019-Short-Film-HOF1-768x400.jpg)