David Lynch was, is, and will always remain one of the most significant voices challenging cinema’s boundaries as a spiritual art form. Some directors make films for the mind, others make films for the soul; Lynch had it both ways, insofar as his incorporeally inclined vision was one that, clearly, came about from the recesses of a brain that knew exactly what it wanted to say, and how it wanted to say it. We may not have understood exactly what Lynch was going for and why (and, for the most part, we still don’t, and likely never will), but those films were all the better for it. In honor of the man taken far too soon, we find it fitting to examine all of David Lynch’s movies to determine where they rank amongst one another.

Though it goes without saying that rankings are rather arbitrary, such a distinction seems especially necessary in the case of Lynch, whose broad appeal seemed largely based around each of our individual capacities to ride anywhere close to his wavelength; some waves are more fulfilling to ride than others, but the roughest seas can be just as rewarding as the calmest waters.

Honorable Mention:

Before getting into the list proper, an aside must be made in order to address the elephant in the room: “Twin Peaks,” being a television show, will not be appearing on this list, nor will its follow-up “The Return.” This may prove to be an unpopular move, as the story is widely revered as among Lynch’s best narrative endeavors—and, in the case of the latter, proof that the director still had the goods over a decade after stepping away from the camera and a quarter-century after stepping away from this universe. But for the sake of consistency in the format we’re discussing, consider “Twin Peaks” and “The Return” to be honorary unranked entries on this list; much like the universe in which the show takes place, they will exist in a loving parallel with whatever’s going on on this other plane of reality.

10. Dune (1984)

Truth be told, a David Lynch tribute in the truest possible sense would probably omit any discussion of his “Dune” adaptation whatsoever. Most tributes to the filmmaker (including our own) have done just that, for the simple reason that Lynch himself has, over the course of his career, been an open book regarding the film’s placement in his heart—which is to say, complete and utter disavowal. Respect must certainly be paid for the first attempt to tackle Frank Herbert’s seismic sci-fi novel to the big screen (Alejandro Jodorowsky’s prior attempt famously fell through), and Lynch makes a concerted effort to marry some of Herbert’s more otherworldly ideas with the surrealist vision for which he’d become emblematic.

The simple fact of the matter is, though, that any attempt to condense Herbert’s novel into a single two-hour film would have been nigh-impossible as it is, and that’s before considering the famous studio meddling that made the entire experience of production an absolute nightmare for Lynch and pretty much all others involved. If nothing else, the legacy of “Dune,” with respect to Lynch’s career, largely boils down to the casting of a young up-and-comer in the lead role by the name of Kyle MacLachlan; for that, at least, both parties would be demonstrably grateful for the rest of their careers.

9. Inland Empire (2006)

Would it be presumptuous to say that nobody’s favorite Lynch film is “Inland Empire”? That isn’t even necessarily a dig at the quality of the film; most of what it has to offer has simply been done (and arguably better) in other Lynch films, but that isn’t, of course, to say that Lynch’s final finished film is completely bereft of any value beyond that qualifier. At a time when digital cinema was only just starting to become a more comfortably commonplace format in mainstream filmmaking, Lynch fully embraced the sterility and pixelated lighting that the format had to offer for the purposes of some of the most nightmarish imagery of his career.

Intuition has always guided Lynch’s directorial style, but in shooting the film without a finished script, “Inland Empire” marks perhaps the most aggressively intuitive approach Lynch would ever apply to his chosen form of storytelling. Across exactly three hours, the film proves to be gradual, often ugly in appearance and undeniably demanding in its pace and dearth of detail—given the distinct register of fright on which Lynch is operating, though, it would be difficult, pointless even, to argue that this is anything other than exactly what he intended.

Also Related to David Lynch Movies: The Anatomy of David Lynch

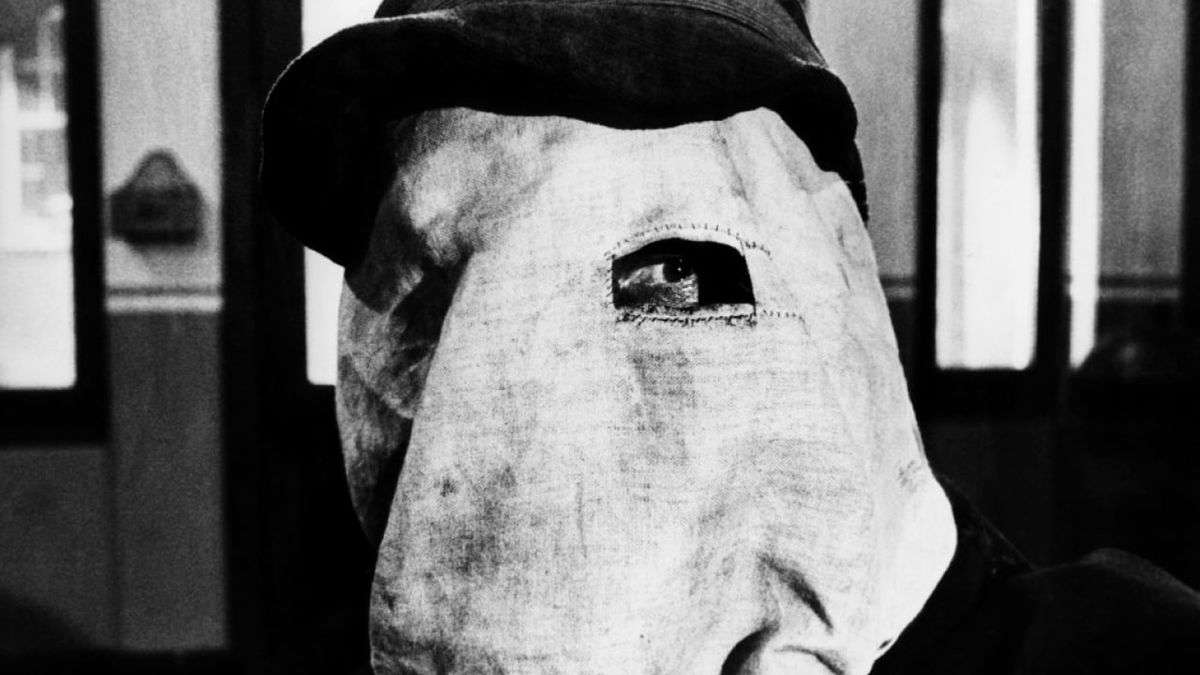

8. The Elephant Man (1980)

It’s always fun to look to the earlier, more challenging works of a filmmaker or actor and connect the dots when they end up in a completely different lane not too far down the line; which executive at Warner Bros. watched “Y Tu Mamá Tambien” and decided “This is the guy we want for our next ‘Harry Potter’ film”? For David Lynch, that unexpected leap came right at the beginning when his debut “Eraserhead”—a perfect summation of everything we know to be “Lynchian”—was immediately followed up with a subdued biopic drama in the form of “The Elephant Man.” Adapting Joseph (changed in the film to John) Merrick’s real-life tragedy, the humanism buried within the absurdity of Lynch’s debut reveals itself in a straightforward and heartrending fashion.

John Hurt’s unrecognizable turn in the film isn’t entirely relegated to the quality of the film’s extraordinary makeup—so significant, in fact, that it pretty much single-handedly convinced the Academy to introduce its Makeup and Hairstyling category the following year. Rather, Hurt’s performance is felt just as much in his vulnerable gaze, hobbled posturing, and frail vocalizations, painting a vivid picture of a life sidelined as little more than a grotesque attraction for an uncaring public. In “The Elephant Man,” Lynch, so often a force of distressing allure, projects Merrick’s life instead with unadorned compassion.

7. Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me (1992)

For those lamenting the lack of “Twin Peaks” discussion in this list, rest assured that Lynch, as always, has skirted the arbitrary rules we’ve made up to earn his praise regardless! Truth be told, once you’ve fallen in love with Lynch’s strange mixture of satirized soap opera and genuine soap opera that makes up the series, the prequel film “Fire Walk With Me” may very well strike as something of a disappointment; aside from the horrific expansions of Laura Palmer’s tragic final moments leading up to the show, most elements connecting the film to the series seem tacked-on at best (it’s no surprise that “The Missing Pieces” exists as a collection of extended/excised scenes from the original film).

Once you’re able to get past the fact that David Bowie disappears in a puff of smoke just as quickly as he showed up (and no, that isn’t meant metaphorically), there really is quite a bit to glean from “Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me.” Most notably, among all of Lynch’s most disturbing images, this film may very well possess some of the most viscerally upsetting sequences across his entire oeuvre. Perhaps it’s because Laura Palmer is such a compelling character given two seasons’ worth of mystery prior to the film, but Sheryl Lee’s incredible, crumbling performances add new depth to a beloved universe, shining a horrifying light on one of the absolute darkest corners of the Black Lodge.

6. Wild at Heart (1990)

In a career pretty much defined by floating question marks, “Wild at Heart” might just be the most glaring question mark hovering joyously across Lynch’s legacy. Neither a transcendental horror film in the vein of “Mulholland Dr.” nor a stripped-back drama akin to “The Elephant Man,” the film that would earn Lynch the Palme d’Or is quite possibly the filmic embodiment of the very concept of an anomaly; the best way to describe the film in all of its eclectic glory, I suppose, would be to simply say that it stars Nicolas Cage.

Always a casting choice that will, if nothing else, compel, the Lynch/Cage pairing proves to be nothing short of enchanting, as the eccentric actor is entirely attuned to whatever oddball frequency his director appears to be channeling here. A distinctly American romance of a distinctly visceral nature, “Wild at Heart” remains just as mystical as any one of Lynch’s most celebrated works, all the while exploiting that attitude for an atmosphere of madcap zaniness that, as always, remains tethered to the spontaneity of its primary subjects. Of course, it helps when one of those subjects is Cage donning a snakeskin jacket, but hey, sometimes a cheat code simply has to be admired.

5. The Straight Story (1999)

In 1994, Alvin Straight rode 240 miles from Iowa to Wisconsin on top of a riding lawn mower, all for the purpose of visiting an ailing brother with whom he’d grown distant. Something in this simplistic tale struck a chord with David Lynch, and the result was a notion that, up until this point, seemed entirely oxymoronic even in concept: a Disney-produced David Lynch film. Naturally, “The Straight Story” isn’t exactly the sort of family fun one associates with the House of Mouse, but in this tale, Lynch finds a tenderness in the desire for familial reconnection that could make any relations reach for the telephone to check in on an estranged loved one.

Anchored by Richard Farnsworth’s grizzled but entirely friendly demeanor, “The Straight Story” is a testament to Lynch’s pervading empathy for all aspects of the human experience—even if they find themselves expressed in ways unusual to the surreally inclined auteur. Rather, the film’s subdued essence makes for the most transparent connection to a filmmaker whose persona would be defined by his capacity to appreciate the little things in life; everything from a ray of sunshine to two cookies and a Coke is just as affecting as the enduring power of brotherhood, and “The Straight Story” distills this area of Lynch’s philosophy to its most affecting form.

Read More About David Lynch Movies: A Tribute to David Lynch: An Impenetrable Visionary Who Lit Up The Darkest Recesses of Our Minds

4. Lost Highway (1997)

Just before “The Straight Story,” Lynch would begin a trilogy of Los Angeles-set features turning the City of Stars inside out as a breeding ground for what can only be described as unfiltered nightmare fuel. “Lost Highway” begins this trilogy by pulling us into its vision of L.A.’s deserted roads with a slick, impossibly transfixing sense of place akin to a neo-noir film. At the same time, “Lost Highway” is potentially the horniest of Lynch’s films, a prospect that seems almost antithetical to its nightmarish designs until you realize, as Lynch did long ago, that these elements prove to be entirely complementary to our understanding of the human psyche.

Unlike the trilogy closer “Inland Empire,” “Lost Highway” is distinctly gorgeous in its envisioning of California horror, though never to the point where its allure takes away from the distinctly discomforting ambiance Lynch was always adept in crafting. Malleable in its structure beyond any point of attempted explanation (Lynch himself described it as something of a “psychogenic fugue,” likely the closest we ever got to a direct explanation of one of his films from the man himself), “Lost Highway” is one of the most potent examples of experiencing Lynch’s films before (if ever) understanding them.

3. Blue Velvet (1986)

Every person has that one David Lynch movie that makes it all click—that one film in which the unbounded vision of the unapologetic artist simply makes sense, even if it doesn’t quite “make sense.” For this writer (and, undoubtedly, for many) that film was “Blue Velvet,” in many ways a landmark moment in the post-”Dune” doldrums of his career. It’s widely understood that Lynch only took on the disaster that was “Dune” in the first place so as to secure funding for this following passion project, and in its disturbed view of American suburbia, one gets the sense that they’re watching an artist who could only ever meet their greatest potential without compromise.

Joined not only by a returning Kyle MacLachlan but a first-time collaboration with Laura Dern, “Blue Velvet” would, in this sense, become a defining moment in Lynch’s career that would color his oncoming projects with every shade that could adorn a white picket fence. But of course, if “Blue Velvet” is defined by any casting choice, it’s not that of the fresh-faced MacLachlan and Dern, or the seductively mysterious and sympathetic Isabella Rossellini, but that of Dennis Hopper, embodying every idea Lynch’s horror could muster in one demented human form to show us where the truest terrors of his world actually lie.

2. Mulholland Dr. (2001)

Viewed by many as his unabashed masterpiece, “Mulholland Dr.” has certainly earned its praise as Lynch’s most alluringly elusive feature. Originally conceived as the pilot of a TV show, the project was thankfully retooled to the cinematic medium, a blessing considering how much Lynch’s projected vision of the Hollywood Hills feels so ephemeral in its appeal that to spend any more than the allotted 146 minutes in this world would feel like peeking into a universe we were never meant to experience with quite as much privilege as this.

Another one of Lynch’s Leading Ladies who would find her greatest calling in the care of the loving madcap genius, Naomi Watts inhabits his world with equal parts naïveté and knowing temptation, a crucial mixture for a film relying so heavily on the metaphysical appeal of its setting as filtered through the Lynchian eye. It’s rare enough—a near-impossibility, in fact—for a film to receive a Best Director nomination at the Oscars without recognition in a single other category; “Mulholland Dr.,” owing to Lynch’s singularity as a force of nature, is one such film, and only someone in his position would be able to turn such a gross lack of acknowledgment into something of a distinctive victory. The only gold David ever needed came from gazing at the majesty of the sun, anyhow.

1. Eraserhead (1977)

Not many directors can claim to have achieved everything their artistic skillset could offer the first time behind the camera, but David Lynch was one such figure with his show-stopping debut “Eraserhead.” Not to say that things “went downhill” from here, but the director’s low-budget introduction is simply a near-perfect marriage of impenetrability and interpretable appreciation that would be impossible for basically any filmmaker to top further down the line in their auteurist journey. Though Lynch would attest until his dying breath that nobody had ever correctly interpreted what the film actually represented, “Eraserhead” offers such a clear-headed view of whatever it’s supposed to be (the common interpretation is the fear of parenthood) that, even if you want to assume Lynch was lying, you’re hardly in a position to care one way or the other.

Jack Nance, yet another Lynch regular, inhabits the role of parental terror (“allegedly”…) with the most gleefully nervous head-turning and eye-bulging in cinema history; you’re likely to assume he found inspiration for the role by observing terrified pigeons. Sure enough, it’s that enduring sense of off-kilter humor that firmly cements “Eraserhead” as the hailing of a unique new talent who cast all preconceptions of tone to the wind with his own personal concoction that went above and beyond anything else being done at the time, or since.