Yep. They’re both two of the greatest, most entertaining and most riveting yarns about gangsterdom ever put to screen, both by the same incredible director, but I would wager Martin Scorsese’s follow-up Casino (1995) is better than its similar sibling film Goodfellas (1990). I’d even goes as far to claim that The Departed and The Wolf of Wall Street are better than Goodfellas, but that’s for another time.

Goodfellas is often heralded as one of the very best crime films ever, or simply one of the best films ever. It sits comfortably as the 17th highest rated film on IMDB, whereas Casino does a decent job at 143. Goodfellas was voted best film of all time by Total Film critics in 2006, surpassing the likes of Citizen Kane, Vertigo, and Jaws, whilst Casino was absent, and appears at no. 94 on the American Film Institute’s Top 100 Films (again, no Casino).

Although Casino has its high praises here and there, it stands as a little sibling to Goodfellas, despite it seeming like a larger film. Perhaps whether one prefers one film to the other may depends on what story appeals to them: Goodfellas is a personal story seen through the underbelly of the mafia, whereas Casino is a sprawling story of the control gangsters had of the Las Vegas casinos throughout the ‘70s. Whereas Goodfellas is examining tucked-away characters trying to evade the law, Casino shows characters who are more wildly extroverted and unabashedly visible, and the expressions of these characters rubs off onto the films respectively.

Both films are anchored by a leading performance, and although the story of Goodfellas feels like it’s covering more of a life story than in Casino, I prefer Robert De Niro’s Ace Rothstein to Ray Liotta’s Henry Hill. As intimate as Henry’s story gets, Ace’s is both intimate and grandiose. The film is able to cover both his up-and-down relationship with his wife, as well as his enormous and controversial place in the Las Vegas gambling scene. It seems to cover more of the personal, the crime work, and the eccentricities of Ace than Henry in Goodfellas.

Related – 10 Facts You ‘Probably’ Didn’t Know About Goodfellas

Both films are also dealing heavily with the romances of the lead characters: although Karen (Lorraine Bracco) has her own narration in Goodfellas and Ginger (Sharon Stone) doesn’t in Casino, Ginger still seems to leave more of an impression than Karen. These two characters are both playing what could’ve been typical gangster’s brides roles, but through the tremendous acting and insightful writing, they come across far more multifaceted than clichéd. But out of the two, Ginger is the superior stunner, as she is written to be a highly confident and controlling, though acted with a wildness that makes her susceptible to her greed and downfall. She’s just that little bit more of an engaging character, as Karen’s character feels more dependent on Henry.

But of course, the deciding factor for which Scorsese master-work is better comes to down to Joe Pesci. A powerhouse actor who’s arguably delivered two of his best performances in his scant filmography with these two films, his ruthless, impulsive, and amoral Tommy De Vito in Goodfellas earned him an Oscar, but his equally commanding and rather threatening Nicky Santoro didn’t quite accrue as much praise.

Pesci is simply more powerful, more outlandishly charismatic, and more entertaining to watch in Casino, and that may have something to do with Casino having better lines for him as well. “They’d bring me in for everything. If a guy fucking tripped over a banana peel, they’d bring me in for it.” “I lost control? Look at you, you’re fucking walking around like John Barrymore! A fucking pink robe and a fucking cigarette holder? I lost control?”, “Take this stiff and pound it up your fucking ass! Hit me … Take this one and stick it up your sister’s ass!”

As you can see, the dialogue is particularly vulgar, filled with profanities being flung about from one character to another amidst regular conversations about work and crime. But writers Scorsese and Nicholas Pilleggi turn such vulgarities into a riveting and appropriately ugly way of portraying such a fraught and risky criminal business, just like they did in Goodfellas. The coarse language not only has an electricity to it as it’s delivered by actors who have such an understanding of profanity, but also adds an ever-mountainous tension throughout the film. Both films are written to an inch of their lives, but Casino just about wins this round due to not only the better Pesci lines, but how this dialogue is interweaved through such a dizzying and dazzling story.

Also, Read – Lookback on Scorsese: Mean Streets [1973]

Even the cinematography seems like it’s been brought up a notch with Casino. Goodfellas impressive roaming camerawork gives life to some otherwise standard and realistic scenery. Casino is more adventurous, continuing with the stunning steadi-cam prowess, but also making more of the bright, exuberant, and overwhelming lights and colours of the casinos, not to mention Ace’s very loud colour coordination in his attire. I suppose Goodfellas can’t help but be a drearier, more sullen looking film of underworld gangsters as opposed to Casino’s bright, luxurious portrayal of Las Vegas gangsters who don’t mind hogging the spotlight.

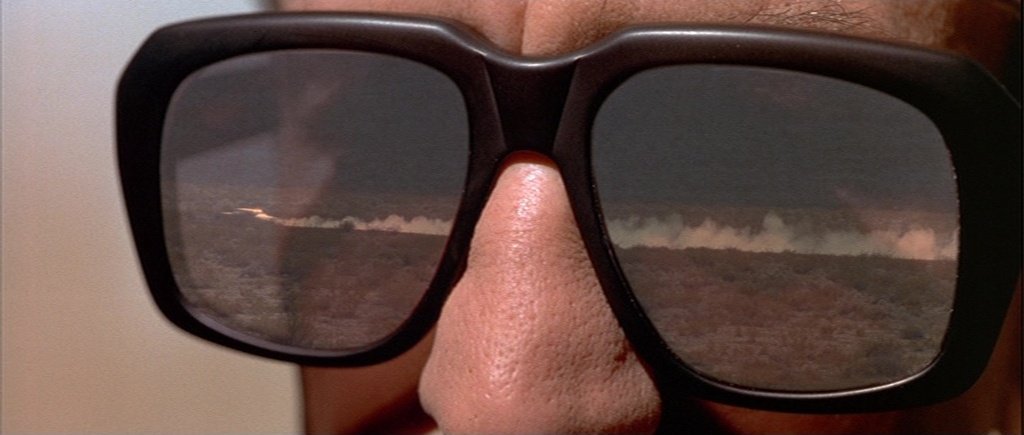

But it all adds up to what Casino has that Goodfellas doesn’t have: a real palpable sense of location. Casino is a film that screams Las Vegas, especially of its pre-corporation era, but Goodfellas is less concerned about presenting the exterior and more concerned about sticking to the tight and hidden and dingy interiors. One of the most memorable shots in Casino is a night-time aerial shot showing all of Las Vegas in all its own unique glory, before a very memorable cut to the barren desert as Ace and Nicky in voiceover talk about the logistics of digging a hole for someone’s body.

With Casino clocking in at near three hours long, thirty minutes longer than Goodfellas, it has a more epic feeling to it: it seems to cover more characters and more of the criminal situation they’re in, all the while never feeling confined or restricted. Although Scorsese and co. introduced not only a strong new cinema language, but a new ecstatic viewpoint of criminals in Goodfellas, it still feels like a solidly impressive stepping stone for what would be an even more ultimate master-work just five years later with Casino. Although it was dismissed by some as a Goodfellas rehash when it was released, hopefully Casino can be re-evaluated as its own remarkably made film.

![The Severing [2022]: ‘Slamdance’ Review – Calisthenics that careen into tedium](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/The-Severing-Slamdance-768x576.jpg)

![County Lines [2019] Review: A gut-wrenching tale of a teenager peddling drugs](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Country-Lines-1-highonfilms-768x576.jpg)