This article will explore how Salvador Dalí’s contributions to Surrealism reflect the interplay between art, aesthetics, and psychoanalysis.

Abstractism is an artistic emancipation from conformed reality. To understand something in its entirety, it is crucial to prevent deviation by laying boundaries and defining it. One’s reality is constituted through one’s perception of the world, and that perception is a product of societal conditioning. On a conscious level, thought processes are limited. However, the subconscious and the unconscious do not follow a similar pattern. The human mind executes suppressed thoughts, memories, urges, and desires through dreams; the central quality of dreams is the unraveling of their meaning through interpretation. Sigmund Freud, through his book Interpretation of Dreams, published in 1899, introduced dreams as gateways to one’s repressed psyche and gave them the quality of a narrative despite their bizarreness.

Man was now recognized as having two narratives that ran parallel to each other which came out of the same mind; this introduced the idea that the same reality can be represented in two ways: one that is rationally understood and another that needs to be interpreted (in other words, psychoanalyzed). World War I jolted half of the globe into conflict and disruption, leading to the launch of the Dada movement in Zurich by poets and artists like Tristan Tzara and Hans Arp in 1916. Influenced by other avant-garde movements like Cubism, Expressionism, Constructivism, and Futurism, Dadaism’s aesthetics mocked the materialistic and nationalistic attitudes of the bourgeoisie.

One of the first artworks to get recognized under the movement was by Francis Picabia called Ici, C’est Stieglitz (translates as Here, This is Stieglitz) in 1915, showing a camera with automobile gear-shifts and ‘IDEAL’ written in Gothic font above the lens. A traditionalist would ridicule the artwork and call it ‘nonsense,’ as the artist intended. Another renowned work comes from the German-Swiss artist Hugo Ball, called Reciting the Sound Poem “Karawane” in 1916, which portrayed a costume Ball designed for his performance of the sound poem, “Karawane,” in which nonsensical syllables are uttered in patterns creating rhythm and emotion, but nothing resembling any known language. The most known of all Dadaist artists is Marcel Duchamp, who chose the mundane yet ‘inappropriate’ objects (like urinal) and exhibited them for artistic value under unrelated names, which added to the piece itself; for example, the urinal is named Fountain.

In 1924, André Breton published the Manifesto of Surrealism, providing the aim and ideology that compiled writings from the two previous manifestos and led to the understanding that the Surrealist movement was more than just a style of art. If Dadaists aimed only for mockery with no commonality in execution, Surrealists sophisticated the Dadaist militant abstractism by characterizing the movement by expressing a profound disillusionment and condemnation of the Western emphasis on logic and reason through constructing an adequate theory. Breton systematizes the Surrealist strategies within Freud’s framework, acknowledging its capacity as a rich source of intellectual stimulation, and believes that it presents a revolutionary spirit of subversion.

Freud wrote, “Up to now, I have been inclined to consider Surrealists, who seem to have chosen me as their patron saint, as incurable nut cases. This young Spaniard [Salvador Dalí], however, with his candid, fanatical eyes and unquestionable technical skills, has made me reconsider my opinion.” The difference between Dadaism and Surrealism was a technical one: Dadaists aimed for distortion without declaring the method to follow, while the Surrealists primarily used the medium of Freud’s psychoanalysis and dream logic. Surrealism served as an important precursor to late 20th-century artistic developments such as Neo-Dada, Nouveau Réalisme, and Institutional Critique while continuing to inspire artists ever since who would apply the style to the context of their times.

The reality of every man is different. One interprets another’s reality through the lens of their own. Conforming to a version of reality can be very limiting. To rise above the limitations of society would mean rising above societal morals, rationales, and expectations. As an art, cinema can be especially powerful in presenting an alternative to common perceptions. If cinema-making is an art, viewing it must be recognized as one too. Surrealist cinema is especially notorious for playing with the audience’s determination to identify the director’s purpose. “Un Chien Andalou” (“An Andalusian Dog”) is disjointed and heavy with jump scenes; the usual expectation of the audience is to watch a film that unravels itself for them.

However, that concept is challenged by the jump from “once upon a time” to “eight years later,” defying the understanding of one phrase indicating a fable while the other as an event taking place in the real world. The film, made in 1929 in Paris, was inspired out of a conversation between Bunuel and Dali on dreams and imagery. Dali’s fascination with the psychodynamics of the human mind can be seen in his paintings and movies. The film consisted of fragmented scenes that were directly out of dreams experienced by the artists — ants crawling out of the hands, clouds slicing the moon. The film was directed with the intention of breaking away from narrative cinema, which was prevalent at the time, and hence, one does not find a logical progression of events.

It was held pivotal that no other way except for psychoanalysis should be able to decipher what the film meant to say. The title, “An Andalusian Dog,” was confusing to the viewers as the movie was shot in Paris, and there were no dogs in the film. Glimpses from Dali’s painting, Honey is Sweeter than Blood, are evident in scenes from the movie. Motifs such as a mutilated corpse of a woman, a dead donkey, a severed human head, etc, are common to both the painting as well as the film. Some look at the putrefaction of the donkey as a metaphor for the state of Spanish establishments. The overlapping of two faces could be indicative of the duality and ambiguity of the human mind and nature.

In the opening scene, Bunuel is seen sharpening his blade with a cigarette hanging from the side of his lips. Like other sharp objects such as knives, Blade holds a sinister connotation. One could associate that with the director’s theatrical preparation of slicing his audience with his work. The following scene entails a seated girl whose eye is sliced open with a blade; she shows no sign of resistance, making the viewers think of her as having come for that act in the first place. That scene, however, draws a parallel with the moon being cut by a cloud, which was a part of Bunuel’s dream in real life and a source of inspiration for the film.

The ending scene shows a boy and girl walking away hand in hand, leading the audience to think that it is a happy ending for them; however, both of them are impaled and dug into the beach, denying the audience their comfort from a happy ending. There was an acknowledgment of surrealism in painting, but bringing it to the genre of cinema was a very radical move and would have been seen as an attack on prevalent film aesthetics. In his manifesto in La Révolution surréaliste, Luis Bunuel writes, “It expresses, without any reservations, my complete adherence to surrealist thought and activity. “Un Chien Andalou” would not exist if surrealism did not exist”, explicitly stating the loyalty of both the directors to the movement.

Surrealist films of Dali and Bunuel were a classic case of the bourgeoisie revolting against the bourgeoisie. “Âge d’Or,” directed in 1930, makes no effort to hide the religious overtones; from chanting Bishops on the rocks to the crucifix, through the film, one comes to terms with savagery that is hidden behind societal institutions and obsession with propriety. Although sexual urges have been used as a medium, one could interpret that as Catholicism’s repression, which would ultimately lead to inhuman acts, as has been seen in the ending scene.

Expression of sexual desire leads to one’s world being turned upside down, seen through events taking an unnatural course: internal and external are exchanged, passionate private love-making takes place at public ceremonies, cows and peasants’ carts invade bed and drawing-room, the killing of a rat by a scorpion, abrupt contraction of space and time. The impossibility of sexual consummation results in violence and displacement and is the source of the film’s many hilarious metonyms, such as the poster that becomes a throbbing finger tantalized by a mass of pubic hair or the bandaged finger stroked instead of the absent and longed-for male member.

“L’Âge d’Or” demonstrates that human beings are no different from animals (or, as the film shows, rodents) who are governed by instinct as the so-called lowest forms of life as they don’t have institutions and customs to govern them. Fascist groups such as Les Camelots du Roi and Les Jeunesses Patriotiques attacked “L’Âge d’Or” at the legendary Paris cinema Studio 28, wrecking the theatre and vandalizing paintings by Buñuel’s fellow Surrealists. Unlike “An Andalusian Dog,” which he calls ‘an encounter between two dreams’ indicating the script being a product of an automated flow in writing, “L’Âge d’Or” was tightly structured, as are most Lubitsch films. Amidst all the narrative disruption and black comedy, this film is a moving recognition of love’s precariousness and transience. When the lovers finally overcome the physical obstacles, consummation is still put off.

Can Surrealist Cinema be considered a separate genre or an aesthetic? I would argue that Surrealist cinema is both a genre and an aesthetic. A genre is understood to be a category of films with similar narrative elements, similarities in audience response, and similarities in filming techniques. One could call Surrealism an offshoot of Dadaism. However, there are a few problems in that claim: Dadaism was clear on what it wanted to express, although it does not directly address how it should be achieved. Dadaist art was meant to be nonsensical and whimsical. In contrast, Surrealist art drew heavily from Freudian concepts, shifting the focus from film aesthetics to the lens used by the audience for interpretation.

Dadaism used art to express political opinion, which was not the same as Surrealism, an intellectual and literary movement. Despite a similarity in ideology, both movements differ in agenda, making it valid to consider Surrealism a separate genre from its predecessor. Unlike a lot of aesthetics that had developed due to audience’s demand or positive reception, some either die entirely (like melodrama) while others are restricted only to a specific time period (like silent films with no background score); however, Surrealist aesthetics continue to be applied in cinema even today.

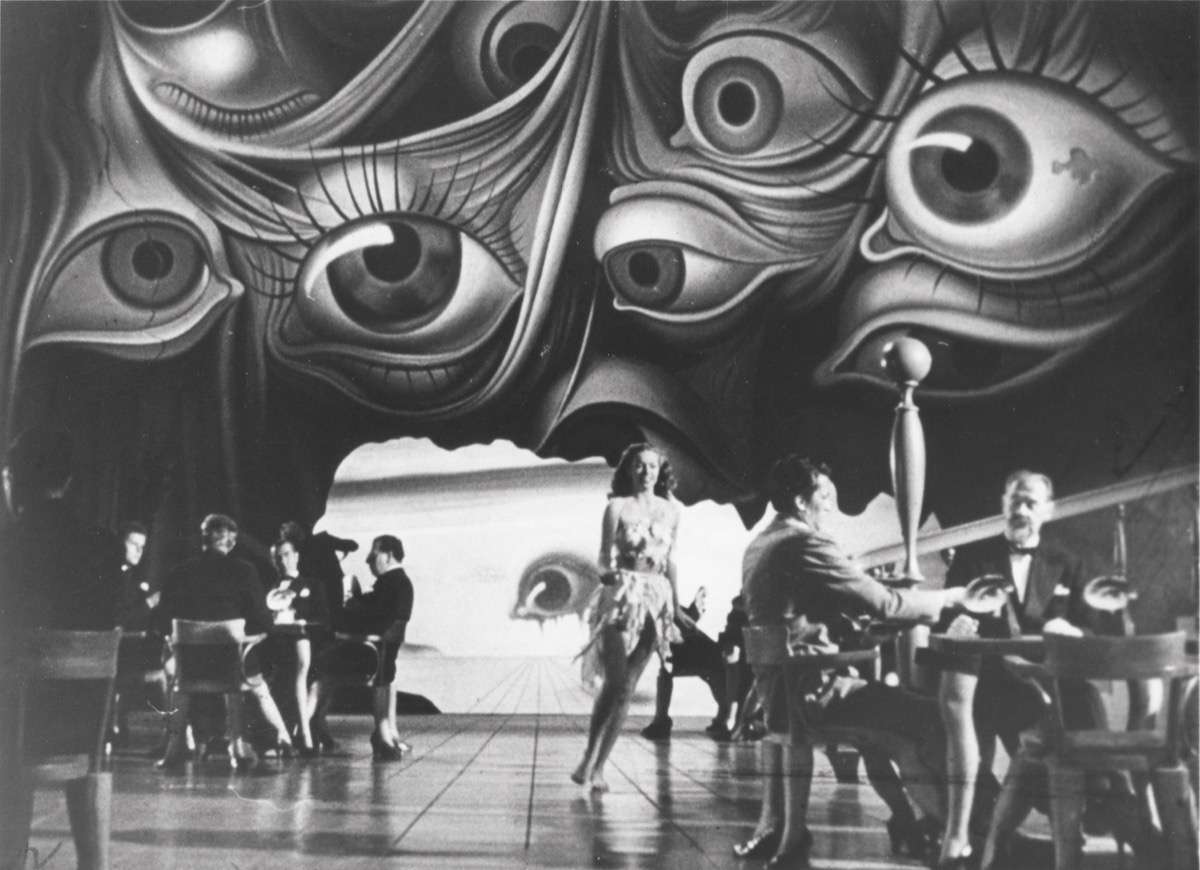

In Hitchcock’s “Spellbound” (1945), Dali was taken into the project to create a pathbreaking dream sequence in the film, knowing fully well that it could become the defining element of the film. The sharp architectural quality of the scene was executed with photographic precision as opposed to earlier filming techniques of blurring to indicate a dream. Surrealism as a genre might not have survived intact, but the aesthetics specific to Surrealist cinema have been passed down through the years. David Lynch is probably the most- known surrealist director of contemporary times and is considered to be the most important director of this era and the Renaissance man of modern American film-making. While considering his films, two things are common: his works are known to make the viewers uncomfortable; they cannot be interpreted entirely through the lens of common sense.

His movies are considered ‘offbeat’ and otherwordly, though he is recognized for the very stylistic elements, which makes him one of the best contemporary auteurs. Surrealist cinema shocks the audience by breaking the restrictions imposed on imagination and creativity, dealing with topics such as sexual instincts, death, hate, violence, etc, which triggers one’s instincts to react due to the conditioning by society. Shocking the audience ensures a reaction from them; hence, the films are not easily forgotten. Subtlety might ensure societal propriety, but it fails to leave a deep impression on the viewer.

Art house cinema, for example, is considered ‘sophisticated’ due to the subtlety in aesthetics and intellectual overtone. However, it fails to significantly impact the audience unless they take the psychoanalytical route for viewing. Dali, in particular, found filmic expression in his paintings, which had a significant impact on the surrealist movement, giving him the title of ‘Father of Surrealist cinema.’ Thus, one can say that Surrealism is both, a genre as well as an aesthetic.