Sidney Lumet was one of the most important American directors to ever live. Evident through his immense filmography, he was a key director of dramas and thrillers throughout a number of decades, particularly in the ‘70s with regarded classics such as Network, Serpico, and Dog Day Afternoon – this series will cover some of his lesser known directorial efforts that perhaps should be as esteemed and as discussed as these works.

Although Sidney Lumet would later make films with varied locations, his early work felt more theatrical and made use of very lengthy scenes in very few locations. One of his earlier examples of this was The Hill, a cross between a war film and a prison film – it doesn’t show the actual combat of war, but it is steeped in the utterly gruelling modes of exercise and discipline (a la the training sequences of Full Metal Jacket), as well as the inhumane and disregardful conditions of prisons.

Although Sidney Lumet would later make films with varied locations, his early work felt more theatrical and made use of very lengthy scenes in very few locations. One of his earlier examples of this was The Hill, a cross between a war film and a prison film – it doesn’t show the actual combat of war, but it is steeped in the utterly gruelling modes of exercise and discipline (a la the training sequences of Full Metal Jacket), as well as the inhumane and disregardful conditions of prisons.

The titular hill is a steep, two-way, man-made sandy hill centred in a British military prison in Libya, used for prisoners to punishingly bring themselves up and down its hot, dirty surface. We are upon the top of it in the film’s opening shot, seeing a tired soldier trying to make his way up it yet again and succumb to passing out – the craned camera pulls back to reveal the enormity of the hill and the prison facility it’s housed in. When the new rag-tag military prisoners are introduced to it, and promptly told to give it a few runs, we are looking down at the soldiers from its peak, the intensely hot air piercing through the sound design.

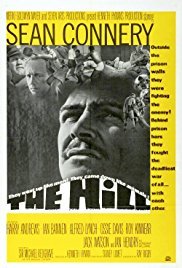

The Hill is seen through the eyes of these newcomers, the most head-strong (and, perhaps correlative, the most brutalised) being Roberts (Sean Connery). After being run through a series of brutal drills, including runs with the hill, Roberts’ cell-mate collapses and dies in their cell, seemingly of over-exhaustion – this prompts Roberts to accuse Staff Sergeant Wilson (Ian Hendry) of overworking this prisoner to death.

From this point on, the film charges forward with a forceful momentum, heading along to its sharply gut-punching (figuratively and literally) climax, after a fairly slow (and fairly wonkily edited) beginning. Like the hill itself, the film slowly trudges its way up as it gradually introduces each character (of the newcomers and the assortment of prison staff), repetitively, yet importantly showing their physical endurance being pushed, before it reaches a height with the death, and then the film falls down the other side of the hill, hurtling faster and more ruggedly towards a climatic stand-off involving the exchanges of arguments and fists.

For such a theatrical experience, it’s hard to pull it off without outstanding actors giving it their all. The performances of the newcomers must be commended, not just for their gruelling physicality (plenty of long unbroken shots of them hurling themselves up and down the hill), but for the emotional toll it takes on them that they so palpably display.

Very much the most memorable is Ossie Davis as Jacko, whose performance is as confident as any of the other leads, but far more fun. Once he hits breaking point, it leaves him denouncing the military, throwing off his uniform, and running around the prison in his underwear, and doing whatever rebellious deeds he pleases with a newfound citizen immunity, which he soaks up with aplomb and provides a much-needed piece of cathartic humour in this dreary story.

Although not stealing the show, the star of The Hill is very much Connery, whose performance quality just about dictates the quality of the film. Once the film heads along to its startling climax, so too does Connery’s sustained bursts of passion and defiance. He is the film’s fiery emotional centre, engulfed further by his jail-mate’s death.

Connery’s appearance in this Lumet film is the first of five he’d appear in the director’s filmography – his next was the rather more comedic, more cocky, and slightly more James Bond-ish role in the crime caper The Anderson Tapes (1971), which was then followed up by his towering performance in the searing drama The Offence (1972), then as part of a terrific ensemble cast in an adaptation of Murder on the Orient Express (1974), and lastly in a more playful role in Family Business (1989).

Connery certainly took the role seriously, feeling it would lead to more intensely dramatic roles. He even missed the premiere of Goldfinger (1964), as it clashed with The Hill’s filming schedule. To him, it was worth it as he wanted to break free from his James Bond typecasting and work towards more dramatically challenging and intense roles – and he sure found a few with Lumet.

Like Fail-Safe (released the previous year), The Hill is a staggeringly affecting thriller-drama that deserves as much attention as Lumet’s most praised and remembered films. Confined to a limited location and made up of lengthy scenes, it slowly lures you into its setting of fraught tensions between characters and then pummels you over the head with its uncompromising ending. Lumet was one of the greatest filmmakers and storytellers in showing how different aspects of the culture affect the individual, and The Hill is clear evidence of that.

![I Am Vanessa Guillén [2022] Netflix Documentary Review: Horrifying true story of a 20-year-old soldier murdered in her Army Camp](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/I_Am_Vanessa_Guillen_Documentary-Review-768x669.png)

![Hawk’s Muffin [2022]: ‘IFFR’ Review – A Metaphor for Perpetual Human Conflict Enveloped in Dystopian Science-Fiction](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Hawks-Muffin-Still-9-768x432.jpg)