The endless and spiralling debate over whether art can be separated from the artist has taken centre stage in the modern cultural landscape as renowned and beloved writers, filmmakers, musicians, and poets face scrutiny over their transgressions, infidelities, and misdemeanours. In this digital era of cancel culture, where information spreads like wildfire, immoral and problematic behaviours are exposed faster than ever, forcing fans to grapple with a difficult choice: defend the art they cherish or distance themselves from the artist behind it. In the field of film, where collaborative efforts create complex works of art, the question arises: Should an artist’s personal controversies overshadow her cinematic achievements on screen?

The argument that an artist’s personal life is pertinent to the appreciation of their art will not hold as an individual’s morals or life choices have little bearing on the quality of their work. While it is contended that a surgeon’s skill or an engineer’s precision may remain unaffected by their personal conduct, art – especially in mediums like film, literature, and music – frequently reflects the artist’s worldview, experiences, biases, and ideologies. However, one must understand that bad people can create great art.

Their work should be judged on its own merit, independent of their personal failings, unless, of course, the art itself echoes the very values, ideas, or actions for which the artist is condemned. If a film moves you, a novel enlightens you, or a painting inspires you, its impact remains valid, regardless of the creator’s moral standing. Art exists beyond its maker, and to dismiss it entirely is to deny its potential for meaning, insight, and beauty.

Oscar Wilde famously argued that art should be a self-contained, beautiful object, independent of its creator and lacking moral or utilitarian purpose. In his words, “Art should strive only to be a beautiful object entirely separate from its creator.” And Wilde feels obliged to state that “The artist is the creator of beautiful things. To reveal art and conceal the artist is art’s aim.” T. S. Eliot, in terms of poets and poetry, affirms that the emotions of art and literature are impersonal. It has its life in the poem and not in the history of poets.

His impersonal theory of poetry states that “the poet, the man, and the poet, the artist are two different entities.” The idea of separating art from the artist was also one of the major critical tools of the New Criticism of the early 20th century. For the New Critics, a work of art is an entity in itself and must stand on its own. It should be appreciated and revered without regard to the life of its creator. “I have assumed as axiomatic that a creation, a work of art, is autonomous,” wrote T.S. Eliot in 1923, and the New Critics followed.

This rule is not just an exception to the writer’s trade. Art, by its very nature, exists independently of its creator, except in the case of live performances. Once a book is printed, a film is released, or a song is recorded, it takes on a life of its own, detached from the hands that shaped it. As time passes, this separation deepens; the artist fades into history, while their work continues to be read, watched, and heard by new generations.

The further we move from the moment of creation, the more tenuous the link between the art and its maker becomes. Should we then allow the flaws of the creator to dictate the legacy of the creation, or does art, once released into the world, belong to those who experience it? To reject art solely because of the artist’s transgressions risks erasing countless cultural touchstones and masterpieces that have shaped history, influenced thought, and evoked deep emotion.

Relying on theoretical foundations such as Barthes’ “The Death of the Author,” Kant’s aesthetic autonomy, reader-response theory, and the collaborative nature of the film, let’s analyse why we should separate the art from the artist. Drawing on diverse film examples, from the visionary works of Alfred Hitchcock to the performances of Kevin Spacey or Dileep, this analysis contends that separating art from the artist not only preserves objectivity in film criticism but also encourages creative exploration.

“The Death of the Author” and Artistic Autonomy

In his influential 1967 essay “The Death of the Author,” French critic and theorist Roland Barthes argues against the practice of relying on the creator’s identity, intentions, and personal history to explain the “ultimate meaning” of the creation definitively. Applying this to film, this theory supports the idea that a movie exists as a standalone artistic entity, where its narrative, themes, visual style, and emotional impact should be evaluated separately from the personal life of the director, writer, or actors. This perspective allows audiences and critics to engage with cinema purely on its artistic and technical merits rather than letting an individual’s private controversies dictate a film’s value or meaning. This approach shifts the focus from biographical criticism to a more open, audience-driven engagement with art.

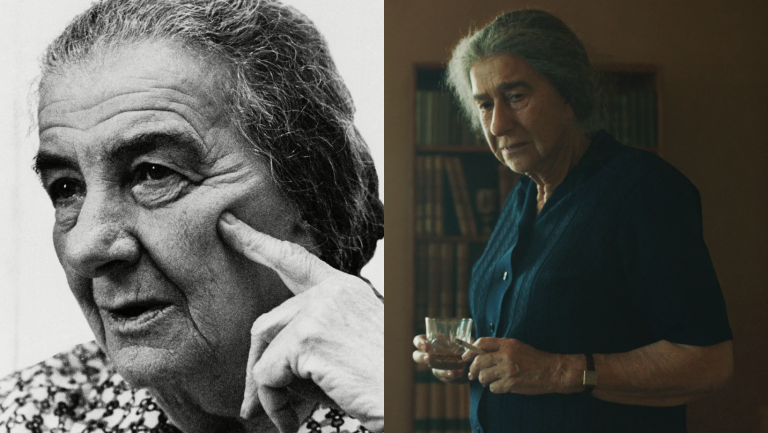

Alfred Hitchcock, who is widely regarded as one of cinema’s greatest auteurs, revolutionized filmmaking with masterpieces such as “Psycho” (1960), “Vertigo” (1958), and “Rear Window” (1954). However, his legacy has been shadowed by allegations of mistreatment toward his actresses, particularly Tippi Hedren, who accused him of harassment and psychological torment during the filming of “The Birds” (1963) and “Marnie” (1964). It wasn’t until less than two decades ago, and that too partly through Donald Spoto’s book Spellbound by Beauty: Alfred Hitchcock and His Leading Ladies, that the world knew about Hedren’s more serious accusations. The book claimed that Hitchcock made explicit and inappropriate demands, “expected me to make myself sexually accessible,” and actively contributed to harming her film career when she refused to acquiesce.

Despite these revelations, Hitchcock’s films continue to be studied, celebrated, and revered for their cinematic innovations, narrative complexity, and psychological depth. His use of suspense, camera techniques (such as the dolly zoom in “Vertigo”), and pioneering storytelling remain influential in film history. There had been rumours about his nasty behaviour towards Vera Miles even before he worked with Hedren.

If Hitchcock had been held accountable during his career, the trajectory of films like Vertigo and Psycho might have been different. While these films have undeniably shaped cinematic history, it is worth questioning whether artistic brilliance should ever come at the cost of ethical compromise. The critical debates of the 1960s, which focused heavily on genre cinema, might have evolved differently, but that does not mean accountability should be sacrificed for the sake of artistic legacy. Consequently, hold the artist accountable for their actions, but let the art stand on its own, crucify the man, not the masterpiece.

Immanuel Kant’s Aesthetic Autonomy

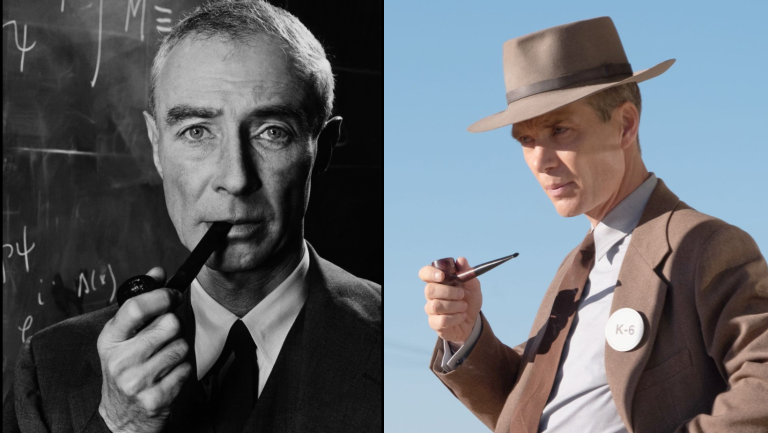

German philosopher Immanuel Kant, in his Critique of Judgment (1790), argued that true art should be appreciated for its form, composition, and beauty, independent of external influences such as the artist’s personal life or moral character. This perspective suggests that artistic merit is inherent in the work itself and should not be judged based on the creator’s actions.

According to Kant, an artist endowed with genius has a natural capacity to produce objects which are appropriately judged as beautiful, and this capacity does not require the artist himself or herself to consciously follow rules for the production of such objects; the artist himself does not know, and so cannot explain, how he or she was able to bring them into being. This concept supports the idea that the value of art lies within the work itself, independent of the artist’s intentions, actions, or even self-awareness. It reinforces the notion that great art can transcend its creator.

In film, this means evaluating cinematography, editing, narrative, and performances without considering the personal lives of those involved. This method ensures that artistic merit is assessed based on objective criteria rather than moral judgments. A relevant example is Roman Polanski, a celebrated director whose masterpieces – “Chinatown” (1974), “Rosemary’s Baby” (1968), and “The Pianist” (2002) – continue to withstand the test of time, leaving a lasting cultural and cinematic impact. One might detest Roman Polanski for his abhorrent crime, and he is a convicted sex offender. It goes without any justification, and his crimes remain indefensible. Despite Polanski’s criminal history and the widespread condemnation of his actions, his films remain critically acclaimed for their artistic excellence, storytelling, and cinematic innovation.

Also Read: 10 Best Films of Roman Polański

Polanski’s representation of the female psyche, especially in The Apartment Trilogy (“Repulsion” (1965), “Rosemary’s Baby” (1968), and “The Tenant” (1976)) and its intricacies is revelatory but when one watches his works, one is always reminded of the capricious nature of his appalling acts. It is deeply ironic and disturbing that an artist who understood, existentially, what it’s like to be a woman also seems to be the same man who victimised a minor. This is the core tension in the art vs. artist debate: Can we admire “Chinatown” as a cinematic achievement without endorsing the actions of its creator? Kant’s theory suggests that we can and perhaps should judge art based on its intrinsic qualities rather than allowing moral judgments of the artist to dictate its worth.

Reader Response Theory

Reader-response theory, developed by scholars like Stanley Fish and Wolfgang Iser, believes that the meaning of a work is not fixed by the artist’s intent but is actively shaped by the audience’s interaction with it. A movie’s significance is derived from how viewers perceive, interpret, and emotionally engage with it, regardless of the personal life or moral failings of the filmmaker.

Stanley Fish introduced the concept of interpretive communities, which suggests that audiences do not passively receive meaning from a work but rather construct it based on their cultural backgrounds, beliefs, and prior experiences. Wolfgang Iser, another key figure in Reader-Response Theory, emphasized the gap between text and reader (or “audience”), arguing that a work is never complete until interpreted. His idea of the implied reader suggests that a film anticipates an audience’s engagement, but the final meaning is always shaped by individual viewers.

To put it simply, once art is created and shared with the world, it becomes a malleable artefact. It transcends its creator, belonging instead to the audience, the ones who interpret, appreciate, and find meaning in it. From the moment it is experienced by others, a work of art takes on a life of its own, free from the intentions or influence of its maker. The artist may shape the creation, but they do not control how it is perceived, understood, or valued. In the end, it is the art that endures, not the artist, and so it should.

Andrei Tarkovsky opined that “A book read by a thousand different people is a thousand different books.” Similarly, in film, this means that no single, authoritative interpretation of a movie exists. Instead, different audiences bring their own perspectives, reshaping the film’s significance over time. For example, Alfred Hitchcock’s “Vertigo” (1958) was initially met with mixed reviews but was later reinterpreted as a masterpiece by scholars and cinephiles, reflecting how audience perception evolves. Moreover, applying Fish’s theory to problematic filmmakers like Roman Polanski or Woody Allen, one could argue that the audience, not the artist, ultimately determines the film’s meaning. A viewer might watch “Chinatown” (1974) and focus on its neo-noir brilliance, while another might see it through the lens of Polanski’s personal history, making engagement with the film deeply subjective.

The New Republic culture critic Josephine Livingstone put forward her opinion on Allen and Polanksi’s films, saying, “I consider Woody Allen and Roman Polanski’s movies gifts, to me and to the culture, even when they’re bad, and I’m never giving them back. I don’t want Allen and Polanski to have control over their own legacies or even over their own works. If they don’t get to dictate how I interpret their films, then they don’t get to control anything about the film industry. We, the viewers, do.” Iser’s theory reinforces that interpretation is a dynamic process, each viewer creates their own version of the film, independent of the filmmaker’s intentions or reputation.

Collective Creation and the Nature of Film

Film is inherently a collaborative art form. Although directors and screenwriters often receive the most attention, a film’s holistic development results from the combined efforts of many professionals, from cinematographers and editors to actors and composers. This multiplicity of voices reinforces the argument that focusing solely on one individual’s conduct can obscure the collective genius that produces cinematic art. “The Birds,” for instance, owes much of its success to Hedren’s performance, the work of special effects technicians, and Bernard Herrmann’s eerie sound design. Screenwriter Robert Towne, cinematographer John Alonzo, and actors Jack Nicholson and Faye Dunaway were equally instrumental in shaping the legacy of “Chinatown.”

“The Usual Suspects” star Kevin Spacey, once one of Hollywood’s most respected actors, faced multiple allegations of sexual misconduct, leading to his removal from the hit political drama “House of Cards.” However, the show itself was the product of a large team of writers, directors, producers, and crew members. When Netflix decided to move forward with the series without Spacey, it acknowledged that while the lead actor was central, the series did not solely belong to him. Similarly, Ridley Scott’s “All the Money in the World” (2017), which originally starred Spacey, chose to replace him with Christopher Plummer and reshoot his scenes. This decision underscored the idea that one individual’s wrongdoing should not tarnish the work of an entire team.

Art and Accountability

The debate surrounding art vs. artist is often presented as a stark binary, either the work must be separated entirely from the artist, or it must be condemned alongside them. However, this separation paradigm carries an unexamined assumption: that when an artist guilty of terrible actions creates a film, book, or song that reflects positive human values, they must have been hypocritical, concealing their true nature. This assumption oversimplifies both human complexity and the function of art itself.

While we may find an artist’s actions repugnant, can we categorically say that they were incapable of moments of reflection, sensitivity, or profound moral insight in their creative work? Art is often a space where contradictions coexist. It forces us to confront uncomfortable truths, challenging facile binaries like “moral” and “monstrous.” This is why most people love Alice Munro’s fiction: “the way she reveals how, at bottom, we are capable of true ugliness and viciousness.” If we only accepted art from people with spotless moral records, would we risk sanitizing art, limiting its ability to engage with human darkness?

The argument for separating art from the artist does not suggest that those who commit grave crimes should escape justice. Holding someone accountable for their actions and acknowledging their artistic contributions are not mutually exclusive. It is entirely reasonable to wish that a director like Roman Polanski had been prosecuted at the time of his crime, even if that meant cutting short his career.

Dileep, one of the most bankable stars in Malayalam cinema, known for his versatility, comedic timing, and ability to portray relatable characters, was accused of masterminding the abduction and assault of a fellow actress, a case that shook the industry and led to protests, especially from female artists and activists. In a post-#MeToo era, audiences demand accountability from public figures, particularly those accused of crimes against women. Ignoring an artist’s actions can be seen as excusing or normalizing their behaviour. More importantly, for the survivor and others affected by similar crimes, seeing an accused figure thrive in the industry can be deeply distressing, reinforcing a culture of impunity.

To be clear, justice should not be sacrificed for the sake of artistic production. However, the question remains: does his past wrongdoing invalidate the impact and significance of his films? Should an artist’s creations be retrospectively reassessed, or even diminished, based on recent revelations? Even if you choose to see Polanski or Dileep mainly as a predator, to erase their connection with the films they made is a very strange position. Ultimately, choosing whether to engage with an artist’s work after learning of their personal failings is a moral decision, one that varies from person to person. It is understandable if someone is too disturbed by Polanski’s or Dileep’s crimes to watch their films, just as it is reasonable for another to admire “Chinatown” or “CID Mooza” without endorsing the director or the actor.

The Sociopolitical Impact of Cinema: Can Problematic Artists Still Drive Change?

Cinema has long been a powerful tool for cultural transformation, shaping public discourse, influencing ideologies, and reflecting the struggles of its time. Even when the artist behind a film is morally questionable, the work itself can still generate meaningful change. Films made by disreputable artists can still contribute to social justice movements, sometimes as cautionary tales, sometimes as vehicles for important messages.

D.W. Griffith is regarded as one of the most influential figures in early cinema, but his most famous film “The Birth of a Nation” (1915) is also one of the most racially inflammatory works in history. It also glorified the Ku Klux Klan and reinforced racist stereotypes, directly fueling white supremacist ideology in the U.S. In response, it inspired Black filmmakers like Oscar Micheaux, who created films to counter racist narratives. It remains a textbook example of how cinema can be used as both a tool of progress and oppression. Do we erase Griffith’s contributions to film language because of his racist messaging, or do we teach his work as a cautionary tale about the power of propaganda?

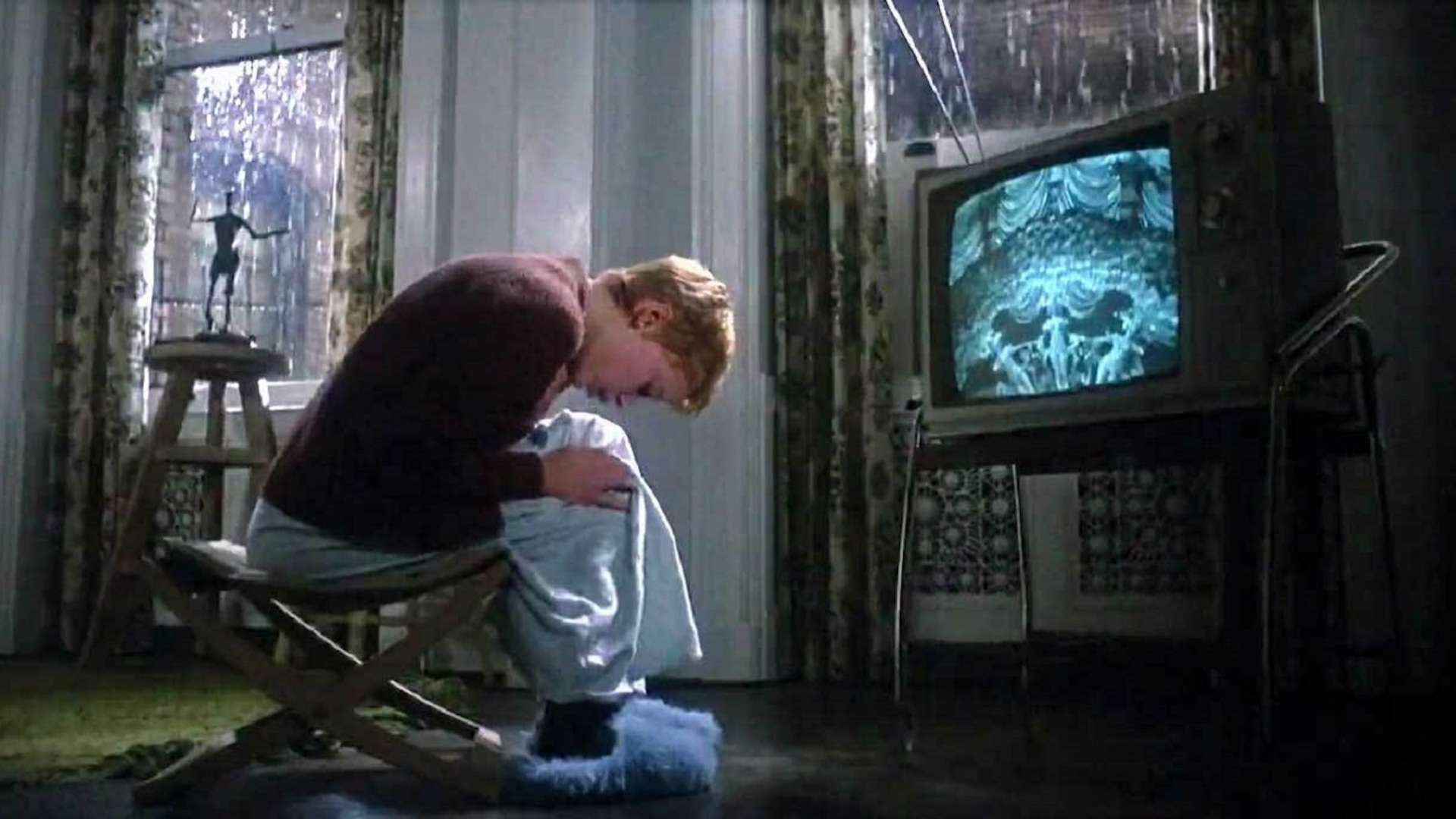

Polanski’s “Repulsion” (1965) is a landmark film in the psychological horror genre that had a lasting sociopolitical impact, particularly in its depiction of female psychosis, isolation, sexual repression, and fear of male aggression. At a time when cinema largely relegated women to supporting roles, Repulsion placed its protagonist, Carol Ledoux (played by Catherine Deneuve), at the centre of a harrowing psychological deterioration. It can be seen as an allegory for how patriarchal oppression and sexual violence affect women’s mental health—a theme that would become more pronounced in feminist film theory in the 1970s. During the 1960s, discussions around women’s mental health and trauma were still stigmatized, and women suffering from psychological distress were often dismissed as “hysterical.” Repulsion challenged this notion by forcing audiences to experience Carol’s fractured psyche from her perspective, using surreal imagery, sound design, and claustrophobic cinematography to convey the disorienting effects of trauma.

Polanski is rightfully condemned for his crimes, yet his film The Pianist, depicting the horrors of the Holocaust, has been praised for its emotional depth and historical accuracy. The film has been widely used in Holocaust education, helping new generations understand the enduring human spirit and the resilience of survivors. The legacy of the film extends beyond its cinematic achievements; it serves as a powerful counterpoint to historical revisionism, standing up against the ignorance spewed by Holocaust deniers. Can we acknowledge Polanski’s inexcusable actions while still recognizing the film’s significance in preserving history?

Woody Allen’s films are known for their introspective, philosophical musings on relationships and art. However, allegations against him have led many to boycott his work. Still, his films continue to be studied for their cinematic techniques and cultural insights. Should “Annie Hall”—a film that redefined romantic comedies—be dismissed entirely because of its creator? Harvey Weinstein, a convicted sex offender, was a leading producer behind some of the most celebrated films, including “Pulp Fiction” (1994), “Shakespeare in Love” (1998), and “The King’s Speech” (2010). His downfall fueled the #MeToo movement, leading to industry-wide accountability. His films, though critically acclaimed, now come with a complex legacy—should they be erased, or should they serve as a reminder of the power imbalance in Hollywood?

While some believe the artist’s wrongdoing tarnishes their work, history shows that films can contribute to sociopolitical progress regardless of who made them. We should engage with films critically and contextually, acknowledging both their artistic merits and the ethical dilemmas surrounding them. Rejecting art outright due to its creator risks erasing valuable cultural discourse, but ignoring an artist’s misconduct is equally dangerous. The best approach may be to view these works through a lens of accountability, discussing not just the film itself but also the circumstances of its creation.