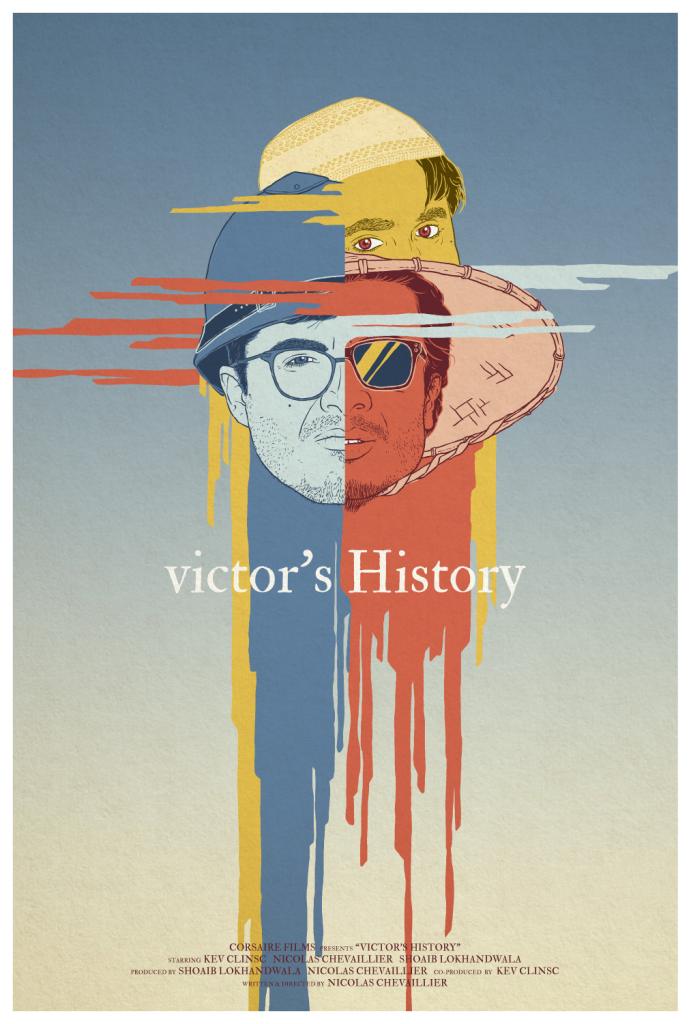

French/American film-maker Nicolas Chevaillier’s micro-budget feature film debut Victor’s History (2017) chronicles young Frenchman’ s efforts to commemorate his dead war veteran father’s legacy. He hires two of his friends (Dorian & Zuhair) to weave the perfect positive narrative for the documentary. The trio sets off on a trip to dig the father’s past which contradicts the glamorized illusions of Victor. They unmask an unsavory episode of grim exploitation and consequently it turns their worlds upside down.

Director Nicolas Chevaillier is a self-taught animator and illustrator who has went to a film school in Los Angeles. Shot over fifteen days in faux-documentary style, the 3-member, multi-cultural crew comprises of Mr. Chevaillier (plays Victor), Shoaib Lokhandwala (producer & plays Zuhair) and Kev Clinsc (co-producer & plays Dorian). They have used a micro setting to instigate a conversation upon the problems of race-relations, privilege, and colonialism.

The director Nicolas sheds more light on the film in the interview below:

I have read that you come from a background of being an animator or illustrator, so what propelled you to make a micro-budget feature dealing with themes of colonialism, nepotism, etc? How did the concept come to be?

Although I went to film school, I fell into animation and illustration after teaching myself the basics. After a few years of working as an animator, I wanted to get back to my live-action roots. Once I decided on making a feature, I wanted to make sure I would be able to execute it with the smallest budget possible, and the least favors asked. I started with the locations, which were available to me, and worked my way backwards from there, engineering the entire story around the limitations. In regards to the themes: Kev (my co-star from Los Angeles) and I often found ourselves having deep conversations about race-relations, privilege, colonialism, etc. Our vastly different backgrounds drove the subject in that direction, and when we added Shoaib (our Mumbai-based producer and cameraman) to the project, it was an obvious choice to plug his background into the debate.

How would you compare the commitment of making animations for television to making a self-funded film with friends?

They both have their benefits and their downfalls. Animation allows for complete control. I can sit down at my computer, and create everything from scratch. If I can dream it, I can execute it. If I don’t like the color of someone’s shirt, I can change it. If I want it to rain, I simply add rain. Shooting live-action is more temperamental. It’s more collaborative. I’m at the mercy of the cast, crew, and even the weather. However, that collaborative nature allows for some really fun creative compromise. The real trade-off between the two, is time. We shot Victor’s History in about fifteen days, whereas an equivalent animation would take me years.

Victor’s History starts off as some playful faux-documentary and delves into found-footage horror territory. What influenced you in making such an unexpected transition?

I’ve always been drawn to mixed-genre films. There is a certain excitement and unpredictability to playing with genre conventions. I also feel that although the tone is more light-hearted in the first half of the film, the debates the characters have with each other only lead in one direction: to some harsh and unspoken truths.

The three characters doesn’t confirm to pre-defined labels: rich one-percenter or poor, victimized immigrant. They are just modern human beings living in multicultural society. How did you deal with your characters? And I think Victor is the exact opposite of Nicolas Chevaillier.

I think the film plays a lot of with expectations, but turns them on their heads. Each character in the film is essentially a representative for a large portion of society. That doesn’t leave room for comical cut-out characters. It was important to me that they remain layered, and that each of them has their own wants and desires. In today’s global society, it’s so easy to interact with people from vastly different backgrounds, and it’s easy to get along. I wanted to touch on the idea of what happens to those relationships when we stop ignoring the sins of our fathers.

There are few interesting visual flourishes, like the upside-down placement of the camera in the moving car, signalling something ominous. Where did that come from?

To veer away a little from the obvious connection with found-footage films, we wanted to make sure that our shots remain more composed. Typically, in these faux-docu style films, the camera simply reacts to what is happening, framing up the most extreme action with little foresight or intuition. Although the camera in our film is an active camera and a prop, we wanted to make sure the pacing and tone of the film is more controlled, and traditional, and therefor, we took care in planning our framing and camera movements.

What’s considered valorous aspect of colonialism is in truth the evidence of long-lasted abuse. Going by Victor’s final act, do you think there’s no way for mending this distorted perception (for the sake of preserving legacy)?

I understand people’s desire to hold onto legacy; to keep the image of their heroes intact. However, I think it’s dangerous, and leads to all sorts of ills, like jingoism and nationalism. Why feel pride for the accomplishment of others? It makes no sense to me. I think it’s a good idea to learn about the deeds of leaders, and the long-lasting pros and cons of their endeavors, but I don’t feel we need to immortalize them as god-like and mint their faces onto coins. Everyone’s champion is someone else’s tyrant. For example, as the European Union decided to share currency, member countries ran into some trouble in what to depict on the currency. France may want to honor Napoleon, but those same euros being spent in surrounding countries, where Napoleon is seen as a dictator and invader, is inappropriate. The United States is struggling right now with statues and monuments built in honor of Southern slave-owners. I’m baffled it’s taken them so long to take down these statues.

In the film, Dorian goes ‘there’s only one reality, truth is truth’. What’s your view on artistic version of reality?

Technically, I agree with Dorian. Objectively, there is only one truth. However, on an individual basis, that doesn’t really matter. We all perceive events differently, and our perception is all that matters to us, subjectively. All we can hope is to communicate well, so that we all can feel and acknowledge each others subjective realities.

What’s your next project? Is there any particular idea or theme you are currently fixated upon?

Shoaib Lokhandwala and I have formed our production company, Corsaire Films, off the back of Victor’s History. We have a few projects in the pipeline, including an animated feature film for adults. Following in Victor’s History’s steps, we have another micro-budget project in the works; this time, a time-travel movie that takes place entirely in one location. We are also putting together some ambitious projects to shoot in India, which I consider my second home, and my muse.

![Get The Hell Out [2020]: ‘TIFF’ Review – Taiwanese Zombie Political Satire is a bonkers thrillride](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Get-the-Hell-Out-Movie-Review-highonfilms-2-768x384.jpg)

![How I fell in Love with a Gangster [2022] Netflix Review – This 3-hour epic Gangster saga is an epic misfire](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/How-I-Fell-in-Love-with-a-Gangster-ak-Jak-pokochalam-gangstera-7-768x405.jpg)