Gus Van Sant is a director of many talents; he has a strong eye for visual composition, an excellent ear for soundtrack choices, and the humanism on and off camera to connect with his talented cast members. Perhaps his finest asset is his ability to balance his experimental and commercial instincts, allowing him to release arthouse classics like “Elephant,” biopics like “Milk,” and passion projects that blend the two while maintaining his identity as an artist and as a queer man in America.

Indeed, after Gus Van Sant’s first movies dealt with themes of homosexuality, he was grouped in with the burgeoning New Queer Cinema in the US. He would introduce his work to the mainstream with a series of successes in the 1990s, including Oscar winner and eternal crowdpleaser “Good Will Hunting.” In the 2000s, his work became more angular and divisive, including a terrific series of films loosely based on real-life tragedies, all of which appear on this list. It was his most prolific and artistically fruitful period, though the next decade or so has proven relatively fallow by comparison. Nevertheless, Van Sant remains a vital and influential voice in independent film who maintains a cult fanbase online, and for good reason. If you’re new to the director, take this as a primer; if you’re already a dedicated fan, enjoy this trip to the highlights of his storied career.

10. Milk (2008)

One of the reasons for Van Sant’s elliptical approach to storytelling in his best films is that he has repeatedly shown he has the ability to competently direct films that are much more conventional. “Milk” is a tightly constructed biopic of Harvey Milk, the first openly gay man to be elected to public office in the United States. Sean Penn won a second Best Actor Oscar for the title role. Still, to Van Sant’s credit, some of the famous thespian’s more extreme instincts are reigned to craft a subtler exploration of what Milk accomplished and how his legacy inspires the LGBT community.

Van Sant’s direction is the perfect vehicle for the sensitive screenplay by Dustin Lance Black (another Oscar winner), translating the somewhat episodic and chronological structure into something thoroughly engaging through rhythmic editing and, of course, the ensemble. Flanking Penn is Emile Hirsch, James Franco, and a career-best Josh Brolin as Milk’s political rival-cum-assassin. We can see between White and Milk Van Sant’s contrasting views on those who hold public office and what they hope to achieve with it. In a time of increased turmoil in the United States, this inspiring story of a courageous political figure is worth a second viewing.

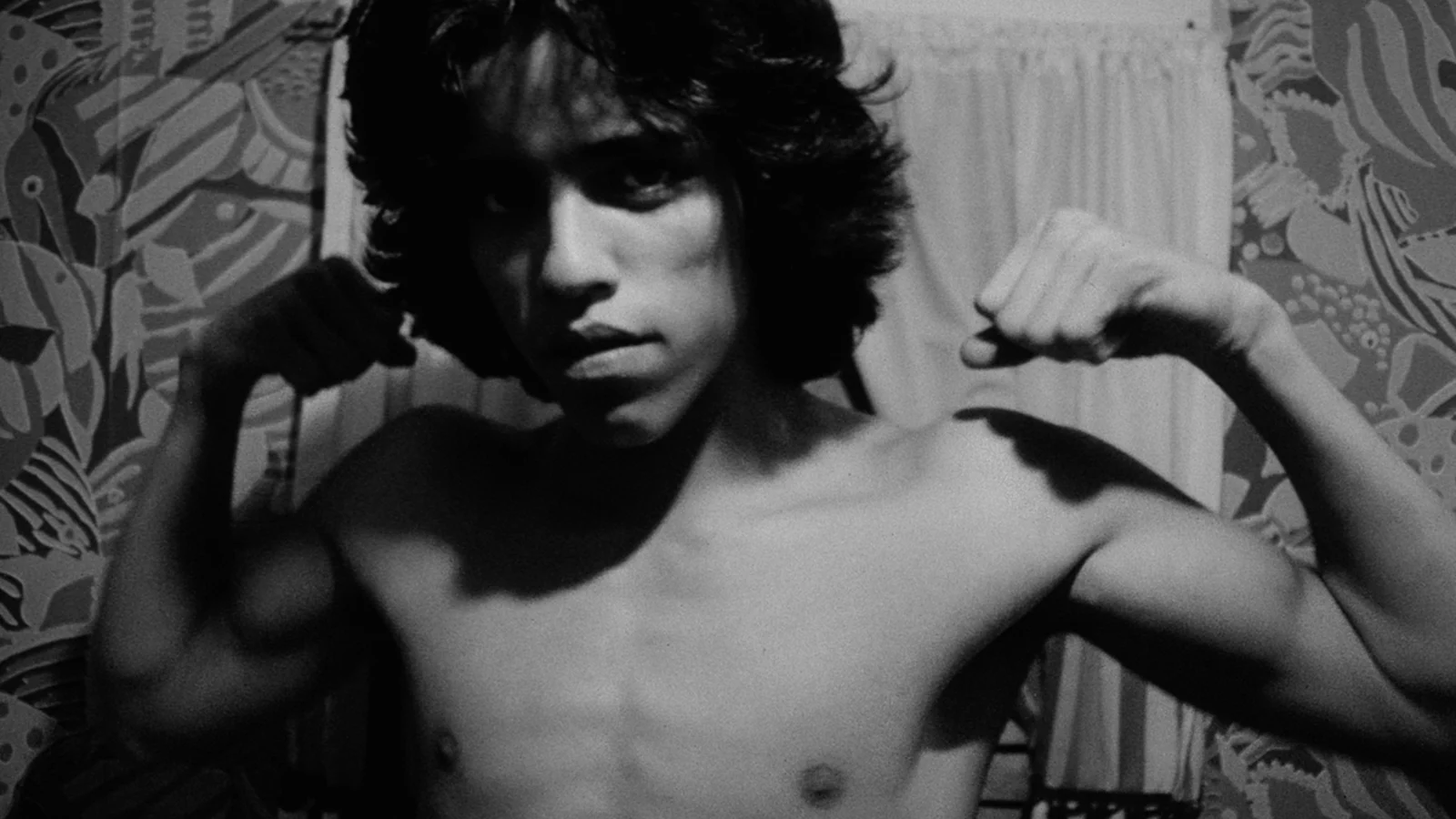

9. Mala Noche (1988)

Milk’s success at the Academy Awards would have seemed unfeasible twenty years earlier when Van Sant’s debut film “Mala Noche” was made on a $25,000 budget. Filmed on gloriously grainy 16 mm, the film is an unvarnished portrayal of a toxic cat-and-mouse game between a man and the two younger Mexican immigrants he desires. An essential text of New Queer Cinema, “Mala Noche” excels in conveying the complexities of the gay experience, seeing an artistic liberation and freedom in showing a gay protagonist with myriad complexities, not simply viewed as a victimized angel or a slimy pervert.

Working with next to no commercial expectation, Van Sant is as loose and experimental in “Mala Noche” as he’s ever been. He doesn’t feel the need to spell out the morality of the story, which is based on a memoir by local writer Walt Curtis, or define the relationships precisely. The physical body is a source of attraction and violence for the camera, unflinching in showing us how the characters, all played by non-professional actors, look and feel. Unfairly forgotten amid Van Sant’s mainstream breakthroughs in the following years, “Mala Noche” remains a challenging yet rewarding debut feature that established its director as one of the most exciting new voices in American indie.

8. Gerry (2002)

For a while in the early internet, “Gerry” was a perennial punching bag. Here was a movie starring Casey Affleck and Matt Damon, two Oscar winners and major movie stars, where they simply wandered through the desert for several hours with no narrative or character development ostensibly in sight. Time, however, has been kind to “Gerry” as people are increasingly receptive to Van Sant’s ability to sculpt a story with time, utilizing boredom as a narrative asset rather than a deficit. The influence of Eastern European cinema, such as the works of Tarkovsky and Bela Tarr, has become more apparent, and many of the question marks over what “Gerry” was going for have been seemingly answered.

That’s not to say it isn’t a puzzling movie to understand or an often challenging thing to parse through on first viewing. The root of its unorthodoxy is the very act of watching characters move from one space to another without interruption, eschewing the editing techniques that can mold the concept of time in movies. This grounds “Gerry” in a kind of realism that is mind-numbingly literal, but once your brain becomes tuned to this new style of storytelling, you become aware of the slightest variation, and by the climactic finale (when rest assured, something does happen) you’re even more out for the count. It’s a similar trick to the one Chantal Akerman famously pulled in “Jeanne Dielman,” and while “Gerry” may not hit the heights of that masterpiece, it remains a fascinating chapter in Van Sant’s oeuvre and a worthwhile watch for any dedicated cinephile.

7. To Die For (1995)

The brilliantly campy “To Die For” is one of the defining films of the 1990s, a postmodern take on celebrity culture and individualized feminism led by a virtuoso performance by Nicole Kidman. Kidman is Suzanne Stone, a budding news reporter who exploits the useless, horny men around her to raise her profile in the industry. The screenplay by Buck Henry provides countless novel framing devices for the story, all of which are in some way compromised by the artifice of the camera – Stone recording an audition tape, her parents on a talk show sofa. Whatever the true story of Stone’s sudden rise to fame is, nobody is going to speak with honesty.

Instead, the viewers put the piece together for themselves, observing how Kidman’s performance brilliantly transitions from cliched virginal purity to ruthless manipulator. The characterization is brilliantly managed by Van Sant, who knows how to stray into high camp without losing the narrative stakes of the story, not forgetting the serious consequences of Stone’s actions, particularly on the working-class teenagers she exploits for TV fame and, later, individual freedom. “To Die For” today appears to be a cautionary warning against so-called ‘Girlboss’ feminism, in which the worship of the capitalist system forgoes any solidarity among women and ultimately hinders the cause for a more equal society.

6. Last Days (2005)

It is another biopic of another American hero whose death shocked the nation, but this time, its troubled rockstar Kurt Cobain (thinly veiled as ‘Blake’) is under the microscope for the final hours of his life. I’m hardly the first person to denote the Gothic undertones throughout “Last Days,” which operates as a quasi-ghost story narrated by a man from the afterlife. As Cobain, Michael Pitt conveys how the ‘voice-of-a-generation’ overwhelming praise for a music icon can double as a straitjacket, a way to control and manner your behavior. The way Pitt interacts with the supporting cast is desperately sad, but what other approach can a filmmaker take with such a subject?

Alongside “Gerry” and “Elephant,” “Last Days” completes a trilogy of films Van Sant made in the 2000s concerning high-profile deaths. This movie makes an interesting counterpoint to “Gerry,” which depicts two men slowly placed in a tragic situation. Here, the tragedy is heightened by the contrast between the rock star’s fame and fortune pulled into a circumstance that was only broken beyond repair through the lens of his tortured psyche. Van Sant’s camerawork and screenplay offer an effectively haunting look at deteriorating mental health and the ravaging impact of fame. For Van Sant’s diehard following, this is one of his best, and it’s not hard to see why.

Also, Read Articles Related to Top 10 Movies of Gus Van Sant: The 40 Best A24 Movies that You Shouldn’t Miss

5. Drugstore Cowboy (1989)

Van Sant’s second feature and commercial breakthrough is a movie that beautifully melds his eye for ugly and beautiful images. Of course, no image is ever ugly in Van Sant’s world as much as it is gritty in service of the narrative, in this case, following a group of junkies who are perpetual fugitives to fund their habit. Along the way, we get a tour of the bleak Oregon landscape, a location where Van Sant spent his formative years. The state has provided the scenic backdrop to many of his best movies, with its blend of hipster culture and the industrial working class.

Like in his debut, “Mala Noche,” Van Sant draws from an autobiographical work of literature for his screenplay. However, it was James Fogle (portrayed by Matt Dillon as Bob Hughes in the movie) who penned the source material. “Drugstore Cowboy” demonstrates equal sympathy and scorn for each of the rag-tag groups of people with an addiction and their plight. A particular standout is Kelly Lynch as Dianne, whose shifting allegiances are the emotional through line of the picture. Her career sadly never took off the way that it should have, but Van Sant’s certainly did. Having proven his ability to direct big names in complex roles, he was on every cinephiles’ radar.

4. Good Will Hunting (1997)

Gus Van Sant was a vanguard of New Queer Cinema, one of the most acclaimed directors of the early ‘90s, and won the Palme d’Or in the 2000s. Despite this, don’t be surprised if his obituary winds up describing him simply as the director of “Good Will Hunting,” the moving tale of a friendship between an erratic but brilliant working-class teenager and his therapist. The latter was played by Robin Williams in the late comic’s best dramatic turn, one that deservedly won him the supporting actor Oscar: no role has better utilized his instant likability and the levity he can bring to dark subjects.

Credit should also, of course, be afforded to Damon for this movie’s enduring appeal. Not only does he provide the titular Will Hunting with a layered characterization, but he also penned the screenplay with his co-star Ben Affleck. The pair brings their experience and love of Boston to the page and does not valorize or canonize their protagonist; instead, they view him as a product of his working-class surroundings, capable of good and bad. Of course, none of it would work quite so well without Van Sant in the driver’s seat, who proved himself perfectly adept as a director of A-list stars and other people’s screenplays. By recruiting DP Jean-Yves Escoffier (known for his work with Leos Carax and Harmony Korine), he retained the indie spirit of his earlier work and married it harmoniously with a classic Hollywood tale of perseverance and friendship.

3. Paranoid Park (2007)

Two of Van Sant’s three best movies (in my opinion) deal with children afflicted by death and violence. This exemplifies two of his best traits as a filmmaker: his empathy for subjects different from him and his ability to cast unknown professional actors and coach their realism into compelling character work. The high-school environment and skateboarding community of “Paranoid Park” feel authentic and lived-in, the result of Van Sant requesting extras and actors on MySpace. This is a director who is consciously trying to keep his ear to the ground in regard to youth culture, and he succeeds in portraying the vulnerability one feels in one’s teen years.

This is essential to the story of “Paranoid Park,” which essentially adopts the unorthodox narrative and visual style Van Sant favored in the 2000s to explain why a young person would be drawn into a criminal investigation. Similarly to “Elephant” (more on that later), it’s a film that seeks to interrogate human behavior by asking questions about environment, family, sexuality, and class. There is a palpable desire in protagonist Alex (played brilliantly by Gabe Nevins) to fit into some sort of community in order to make sense of his own identity, and his mental torment is partly because his actions now feel removed from his own view of self. For those who are enamored with Van Sant’s use of music, handheld camerawork, and non-professional actors in his other work, “Paranoid Park” is an underrated gem.

2. My Own Private Idaho (1991)

There’s an adage that the best way to understand the United States is to drive through it, which Van Sant clearly agrees with. Born in Kentucky, as a child, he relocated often due to his father’s work, which may explain his unique, impressionistic take on the nation’s landscapes. In “My Own Private Idaho,” Van Sant’s screenplay traverses Oregon, Idaho, and Italy to reposition Shakespeare’s “Henriad” as a sprawling queer adventure, though it is actually defined by the smallest of moments shared between protagonists Mike and Scott.

These two best friends are gay men who find themselves on the fringes of society, one a hustler and the other the disillusioned son of the mayor of Portland. They are played brilliantly by the late River Phoenix, whose career would end tragically short two years after the film’s release, and Keanu Reeves, who, just a year after “Bill and Ted,” delivers a performance of heart-wrenching vulnerability and nuance unrivaled in his career ever since. Van Sant likes showing the un-glamourized faces of non-actors and teenagers in his other films, but in “My Own Private Idaho,” he opts to shoot some of the most beautiful movie stars in the world, highlighting how they stand out in the bleak landscape of the road. The result is one of the most emotive and evocative films of the 1990s, rightly remembered for its social importance and rare beauty.

1. Elephant (2003)

“Elephant” uses the full grab-bag of filmic techniques Van Sant had honed throughout his career to tell the story of a school shooting (based on Columbine). There’s non-linear storytelling, long tracking shots, non-professional actors, and, most notably, a palpable sense of empathy for the subjects. Of course, some of the characters will be victims of the massacre, but others aren’t. Van Sant’s intent appears to be to introduce a smorgasbord of the high school experience and its hardships, almost as if to say it could have been any of them.

Similarly, the scenes that depict the massacre’s perpetrators preparing the shooting eschew simplified narratives in the media about why these things happen – they play video games, watch a documentary on Hitler, and practice shooting; by the time the two boys kiss nude in the shower, you can see once again how Van Sant is disposing of, almost mocking, the media’s notions. The boys shoot a school because they fail to empathize with other individuals beyond their own experiences, as opposed to the other characters who forge connections with people different from them despite their faults and issues. This conclusion is at once hopeful for the majority of people, though unsettling in its deliberate failure to provide concrete explanations.

Related to Gus Van Sant’s Movies: The 30 Greatest Cannes Palme d’Or Winners of All Time

Despite winning the Palme d’Or in 2003, after the film was alleged to have inspired a real-life school shooting in 2005, the incredibly violent final act came under intense scrutiny. But to blame a mass shooting on this film is to spit in the face of its message that applying simplistic origin stories to the perpetrators is to insult the victims and trivialize the core root faults of some people and, by extension, the inherent good of most others. “Elephant” is one of the greatest American films of the new millennium, one that remains hauntingly relevant and formally innovative to this day.