One of the greatest directorial minds of her, or any, generation, the late Belgian film-maker Chantal Akerman had a remarkable career, spanning five decades, and a variety of art forms. Her films range from the accessible (The Captive, 2000) to the avant-garde (Down There, 2006), from the joyous (The Golden Eighties, 1986) to the morbid (From the East, 1993), from the broad (A Couch in New York, 1996) to the deeply personal (No Home Movie, 2015); each made with a cerebral, masterful touch. Her contribution toward European and Feminist cinema throughout the late 20th and early 21st century cannot be underestimated and in this retrospective, I aim to examine the thematic through-lines, cultural influence and artistic merit of her filmography- starting from the very beginning.

Upbringing and Debut Short

Born to Polish Holocaust survivors in Belgium in 1950, Chantal Anne Akerman had cited Jean-Luc Godard’s Pierrot Le Fou (1965) as the film that inspired her to become a director. At the age of just 18, she wrote, directed and starred in her debut short film Saute Ma Ville (1968) which was a hit at short film festivals across France.

Also Featuring Chantal Akerman: 75 Best Films Of The Decade

A lysergic, warped thirteen minutes which sees Akerman manically humming her way through a mental breakdown, in Saute ma Ville the French New Wave influences are overt here more than ever, but with perhaps a more psychological edge to it. Via claustrophobic camera work and her own, crazed central performance Chantal Akerman deftly deconstructs the monotony of everyday life- a theme she would of course later develop with her 1975 masterpiece Jeanne Dielman….

A Move To New York

In the same year as her debut short’s release, Akerman left her family and moved to the bustling metropolitan behemoth of 1970s New York City, where she fell in with the avant-garde cinema crowd of the time. Bewitched by the works of Stan Brakhage, Andy Warhol, and Jonas Mekas, she befriended the latter, with the pioneer acting as her mentor in early years in New York.

Living in America, she made two notable works. Her sophomore film Hotel Monterey (1972) was a silent documentary, keenly observing the titular hotel and its occupants with the kind of deft, watchful eye that we have come to expect from her. The result is something strangely compelling, a silent ode to the transportive nature of hotel accommodation and a compelling study of the role they play in modern society. Her next outing, short film La Chambre (1972), took a similarly minimalist approach as the camera presents a still, mostly silent, life, surveying Akerman’s apartment building with the same respect and fascination for the interior that her previous film showed.

Though Akerman spent just four years as a full-time New York inhabitant, these years would shape her directorial voice and identity- with the influence of Mekas and Brakhage as evident in her later works like that of Godard and Truffaut.

Returning To Belgium

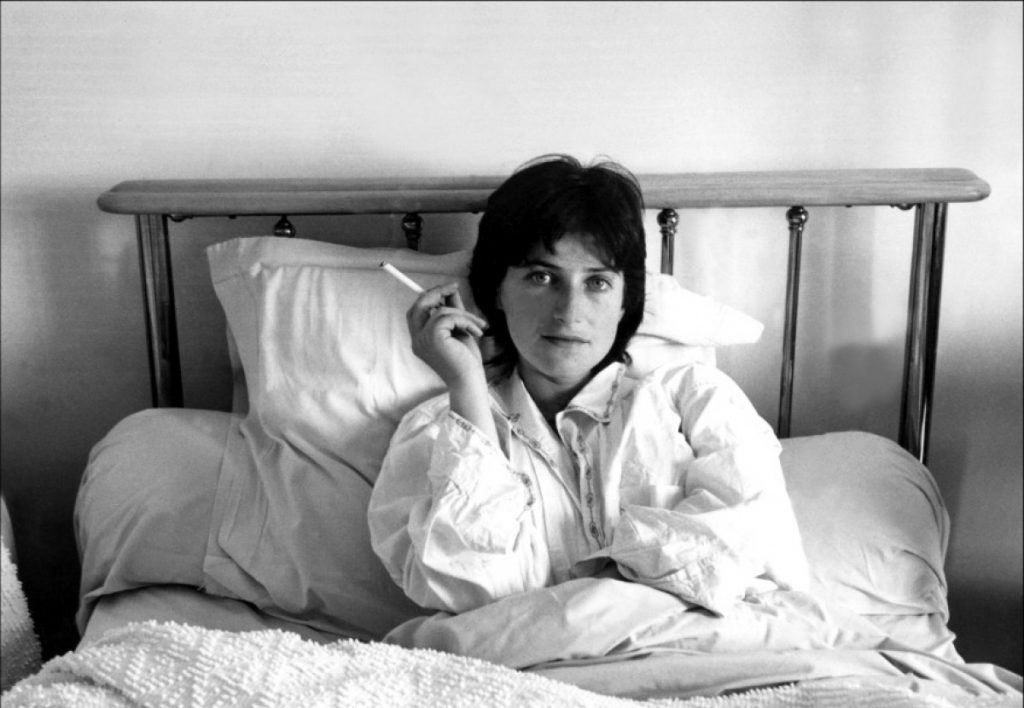

Chantal Akerman returned to her homeland in 1973, and she directed her first feature-length project Je Tu Il Elle (1974) a year later. As is the case with much of Akerman’s work, the film is a boldly minimalist production. A terse eighty-six minutes film that manages to find profundity in life’s mundanity. Our protagonist (played by Akerman herself)’s awakening from prolonged isolation acts as a narrative device to see the human condition through alien eyes. This is, of course, before the famously defiant finale, an immersive and almost uncomfortably intimate lesbian sex scene- the first of its kind to be shown on film. Its a fantastic ending and what makes it work so well, aside from the deft camera work and passionate performances, is that it’s an escape route for the repressed desires of not only the main character but the movie itself.

Though far from flawless, the film is evocative and emotionally resonant in a subtle, hard to define way. The film is meandering and, essentially, plotless but Akerman’s frank directorial style manages to engage the viewer on a deeper emotional level that brings the film above its budgetary shortcomings and proves Akerman as one of the foremost voices of the post-Nouvelle Vague European cinema scene.

Je Tu Il Elle was a critical hit in her native Belgium and across the border in France and the following decades gained more praise as a forbearer to many films exploring queer and feminine identity later down the line. American film scholar B. Ruby Rich once described the film as a “cinematic Rosetta Stone of female sexuality” and it’s not hard to see why.

Buoyed by the success of her first feature film, Akerman applied for a grant from the Belgian government to make her next feature. The film made from the resulting $120,000 would go on to be her masterpiece.

The Magnum Opus: Jeanne Dielman, Quai Du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles

Clocking in at over three hours in length and renowned for its narrative mundanity, Jeanne Dielman, Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles is the towering masterpiece in Akerman’s storied oeuvre. It’s without a doubt the most famous and most acclaimed film she has released but at the same time one of her most angular and uncommercial. It’s certainly true that Chantal Akerman leaves no aspect of Dielman’s seemingly monotonous existence untold and on a surface level reading the film does appear as rather self-indulgent but once the real “drama” starts to unfold it’s extremely compelling film-making.

Our Review of Jeanne Dielman by Chantal Akerman

Following our eponymous protagonist, played flawlessly by Delphine Seyrig, doing common household chores and selling herself for sex in a cyclical routine, the film’s opening two acts succeed in keeping the viewer hypnotically engaged in the banal minutiae of middle-class city life whilst also ingeniously planting the seeds for later conflict. The first three hours or so act as a cinematic exercise, a study on routine and the mind-numbing it can have on people. Even the slightest change to regime Dielman has established (the drop of a spoon, the rattle of a milk bottle) is given profound dramatic significance by Dielman’s underlying reliance on this routine to keep herself sane.

The final twenty minutes themselves (which (SPOILERS) sees Dielman murder a client) almost unravels like a plot twist because of this. It radically re-contextualizes the last 180 minutes of cinema in a way that elevates it beyond its narrative and into one of the defining European films of the 20th century.

Akin to Je Tu Il Elle before it, Jeanne Dielman… is often cited by scholars and critics as a feminist masterpiece and there is clear merit to that point of view. Akerman cleverly uses the domestic setting of the kitchen to comment on not only the typical social constructs of what a woman is (or should be) but the mental, psychological and societal claustrophobia many women of Dielman’s profile suffer from. Jeanne Dielman truly is, as Mark Kermode put it, “the feminine condition as cinema”.

Meticulously shot and performed with uncanny authenticity by all involved, Jeanne Dielman… is a thematically dense-slow burn examination of both the feminine and human condition. Every frame is painted with the deft touch of an auteur at the peak of her powers, in complete control of her craft and that’s what makes Dielman so strangely enchanting and powerful. Truly, a great film.

Hitting Her Stride: Late 70s And Early 80s Work

Chantal Akerman followed up her masterpiece with another one just a year later. News from Home (1976) is a much subtler film than its predecessor in terms of conveying its themes. The film is nothing more than just the letters of Akerman’s mother from the time the director spent in New York read over shots of the city itself but the result is something truly transfixing. It could be argued that News from Home is cinema in its purest form as all of the dramatic weight of the film is brought to the fore via audio-visual association. The movie is shot in typically minimalist fashion with little in terms of visual metaphor or shorthand but the sound design and gorgeous, enfolding shots of New York submerge the viewer in the isolation of living in a bustling, metropolitan city can bring. The sounds of subway trains and pedestrians slowly overgrow the emotion of Akerman’s mothers’ letters to a poetic, rhythmic extent. Simply put, another masterpiece.

Featuring Chantal Akerman: 15 Best Films of 2016 Directed By Women

1978’s Les Rendez-vous d’Anna was a fictitious but still deeply personal affair- there’s little question who protagonist Anna (a Belgian film-maker promoting her film across Europe) is meant to represent. The film itself is another gem. Slow, but not dull. Forlorn, but not depressed. Searching for answers, but not clueless. The film’s most potent scene arrives when Anna talks to her mother about her Lesbianism in Brussels, you can imagine Akerman and her mother having a similar conversation.

Akerman’s streak didn’t end there. In 1980 she directed the documentary film Tell Me for French television, a moving, 45-minute long set of frank conversations with Holocaust survivors. One of the interviews is, of course, with Akerman’s mother Natalie, whose presence looms omnisciently over the great director’s entire filmography.

The most acclaimed film of Akerman’s early 1980s work is Toute une nuit (1982), a quiet but kaleidoscopic portrait of over two dozen characters experiencing love and loss on a humid night in Brussels. The encounters themselves are perhaps too fleeting and brief to resonate individually but the overall product conjures an indescribable atmosphere that needs to be seen to be fully understood.

From 1982-1984 Akerman dabbled in various cinematic experiments and forms. The Eighties (1983) chronicled the staging of a musical, One Day Pina Asked (1983) was a character study of its subject dance choreographer Pina Baush, and Family Business (1984) saw Akerman film in Los Angeles for the very first time, albeit for an eighteen-minute short film for Channel 4.

Genre Hopping: 1985-1999

Throughout the last fifteen years of the 20th century, Chantal Akerman was impossible to pin down. Contrast the truly delightful, Jacques Demy-inflected The Golden Eighties (1986) to the poetically sad documentary From the East and you get an idea of the range of her abilities as a director. Her muse took her to Texas for racial documentary South (1999), Paris for the Jules and Jim inspired Nuit et Jour (1991) and even back to New York for the accessible, enjoyable yet flawed A Couch in New York which saw her direct big movie stars such as William Hurt and Juliette Binoche for the first, and arguably last, time.

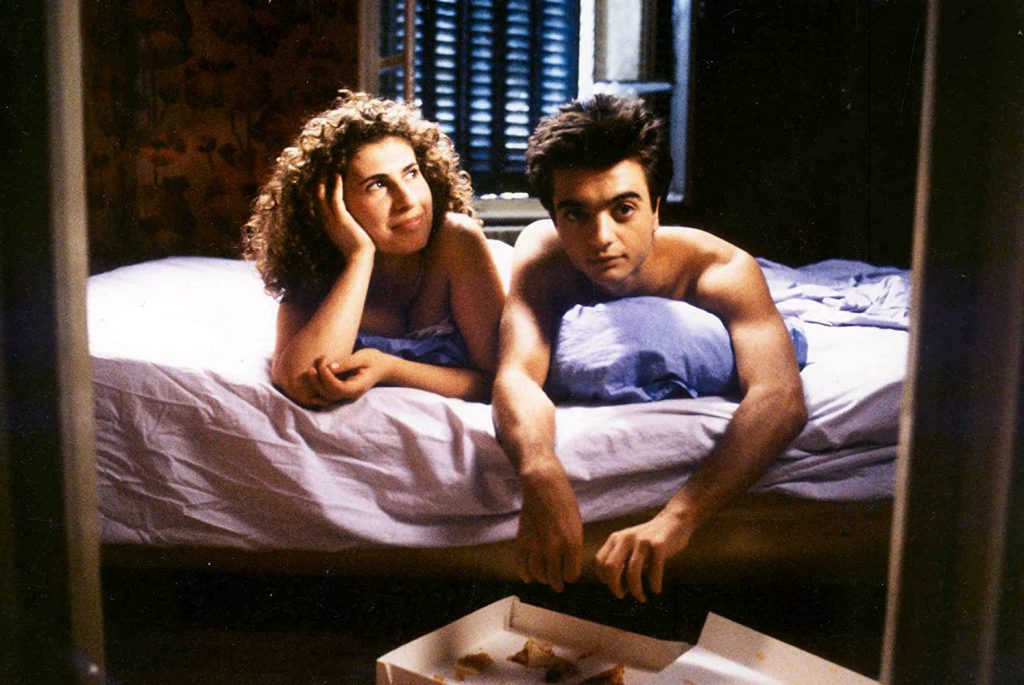

One of the standout films from this period is Portrait d’une jeune fille de la fin des années 60 à Bruxelles (1993), a proto-Before Sunrise in which teenagers Michele and Paul talk about their upbringings, sexuality, and outlooks on existence whilst strolling around the changing landscape of late 60s Brussels. Though the film has historical inaccuracies (despite taking place in 1968 there is a scene in a CD shop) it’s a compelling and charming watch. The scene where Paul and Michele dance to Leonard Cohen’s Suzanne in her cousin’s bedroom and the final shot of the movie are both vintage Akerman.

From 1985 to 1999 Akerman cemented her place as one of modern European cinema’s most prolific and important talents. Whether working in documentary or fiction she created consistently superb romance, drama, musical or comedy films, harkening back to her influences whilst creating a voice and an impact of her own.

Dabbling In The Mainstream: 2000-2015

To say Akerman strayed into conventional, mainstream cinema towards the end of her career would be a falsehood but 2000’s La Captive was far more accessible than any of her previous works, bar A Couch in New York. An adaptation of Marcel Proust’s La Prissonniere, the film was a cold, detached thriller, that mixed Akerman’s minimalist sensibilities with a more traditional psychological thriller narrative. The result is a strange beast of a film and one of her most divisive but one that opened up her oeuvre to a new generation of fans via its limited screenings in England and the USA.

Tomorrow We Move (2004) saw Akerman expand her horizons even further, this time to a neurotic screwball comedy in the vein of Woody Allen- winning the Lumieres Award for Best French-Language Film in 2005. Almayer’s Folly (2011) is probably the best film from the last fifteen years of her career, however.

Related: Feminism And Its Eternal Affair With Filmmaking

“Liberally adapted” (the film’s words, not mine) from Joseph Conrad’s debut novel of the same name, the film starred La Captive’s Stanislas Mehrer as a merchant and Aurora Marion in a fantastic performance as his mixed-race daughter Nina. The film itself takes place in the Malaysian jungle and via Raymond Fromont’s beautiful cinematography you can almost feel the humidity seeping through the screen as gorgeously lit vistas fade into one another akin to a Terrence Malick picture. Gripping, aesthetically flawless and with one of the best opening scenes in recent memory, Almayer’s Folly is a testament to Akerman’s storytelling abilities as well as her directing ones.

But even in the late stages of the career Akerman still made films that were both experimental and deeply personal. 2006’s Down There was a documentary made during Akerman’s stay in Israel that saw her reflect on her Jewish identity, upbringing and, as always, her mother.

Akerman’s mother Natalia once again came to the fore in her final cinematic foray, No Home Movie (2015)- another documentary, this time exploring human communication in the modern age and mostly shot in the confines of Natalia’s apartment. A fascinating and fitting send-off to one of the most diverse and thought-provoking filmographies in modern cinema.

Hyper-Realism: The Style Of Chantal Akerman

To watch a film made by Chantal Akerman is to observe the world in its simplest, most authentic form. Much is placed on the importance of routine and normality, most notably in Jeanne Dielman… but elsewhere in her filmography as well. Akerman, more than any other director you feel, knows that there are beauty and profundity to be found in the very nature of the human condition. She doesn’t need the traditional parameters of narrative storytelling to craft a compelling story, and with her brand of heightened realism, the smallest emotional beats have incomparable significance.

A common complaint of Akerman’s work would be that nothing happens in most of her movies but the fear of nothing is what propels them forward. Whether it’s Anna in Les Rendez-vous d’Anna or Jeanne Dielman herself, nothing is more what they fear than anything else. They always strive to meet new people, do new things, but find themselves boxed into the social constraints of womanhood. The way Akerman uses her style to suggest this feminist side to her work is truly something unparalleled and remarkable. She quietly revolutionized the way female desire and lesbianism were presented on the screen, in no small part thanks to the seemingly plain, simplistic cinematography that has become her trademark.

All About My Mother: The Influence Of Natalia Akerman

Jacques Demy, Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut, Jonas Mekas, Michael Snow: there are a plethora of notable film-makers who have had an overt influence on the work of Chantal Akerman but nobody has had more of an impact on her filmography than her mother, Natalia.

A holocaust survivor (her parents died in Auschwitz), Natalia fled to Belgium after the Second World War and had her daughter Chantal in 1950. A liberal and supportive parent, she didn’t encourage her daughters to marry young and instead to pursue their careers. It paid dividends for Chantal who spent the rest of her career paying homage to her mother throughout her work. 1976’s News From Home is a reading of Natalia’s letters to her child in New York whilst in Down There sees Chantal sending phone calls and voicemail messages to her mother in Brussels from Israel. Her 1998 family memoir Family in Brussels sees Chantal’s voice alternate with that of her mother and most notably No Home Movie chronicles the last few weeks and months of Natalia’s life, chronicling the mind-numbing routine that comes with impending death and/or deteriorating health with the same approach as Jeanne Dielman…..

Through her mother, Akerman manages to explore many parts of her upbringing and identity. Several films in her oeuvre are explorations of the Jewish faith, and Akerman’s role within it, or the Holocaust; using her mother as a lens to see these aspects of her psyche through. And, in both her and her mother’s final cinematic outing, as a way of exploring mental and physical isolation. As Akerman herself put it when promoting the film: “[the film] is above all about my mother, my mother who is no longer with us. About this woman who arrived in Belgium in 1938, fleeing Poland, the pogroms and the violence. This woman is only ever seen inside her apartment … a film about a world in motion that my mother does not see.”

Chantal’s close relationship with her mother is best represented in the darkest of endings though, as just before the film was due to premiere in London Akerman committed suicide, just months after Natalia’s death. Truly, a sad end to the life of one of cinema’s greatest pioneers. A film maverick who quietly revolutionized the European cinematic landscape over a long and storied career. Truly, one of the greatest film-makers of all time.

![Mommy [2014] Review: Powerful, Potent & Profoundly Personal](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/mommy-cover-photo-1-768x432.jpg)