The wide and deep assortment of eccentric, odd characters has kept modern film viewers mesmerized. However, there must be an up-front caveat that the E-word and O-word should never directly enter the realm of actual pathology. As a rule of thumb, even the most well-crafted and well-intentioned films will fail to do justice when attempting to portray the intricacies and tragedies of mental illness. Conversely, we should feel free to relish the deliciously ambiguous nooks and crannies of our behavior, along with our offbeat, even provocative mannerisms. Cinema thankfully affords us this latter opportunity when such boundary issues are sufficiently respected.

The complex filmography of Joaquin Phoenix deserves special attention, given the unevenly played, diverse roles that challenge us to best articulate what might be his most legitimate accomplishments. Aside from some childhood work that extends this timeline, he has been on the grid for nearly thirty years. He has worked with high-profile auteurs such as Ridley Scott, Gus Van Sant, Woody Allen, and Paul Thomas Anderson, but he has duly engaged with others who have more modest tick lists.

SPOILER ALERT: If you’re a devoted student of action or crime films with sword or gun violence, you may wish to read ahead with caution since this particular writer is infinitely less consumed with action rather than projection. This writer’s key driver is how any performer creates a certain presence without a surrogate crutch of explicit violence to help fill in the blanks.

PT Anderson’s Freddie Quell in The Master is an obvious predicate for his later turn in Joker. Still, these roles can leave us feeling cheated, regardless of Phoenix being able to successfully master (no pun intended) the high-octane, psycho-contortionist maneuvering, most notably in Joker. In other words, what’s so great about being a self-absorbed sadist? Not much.

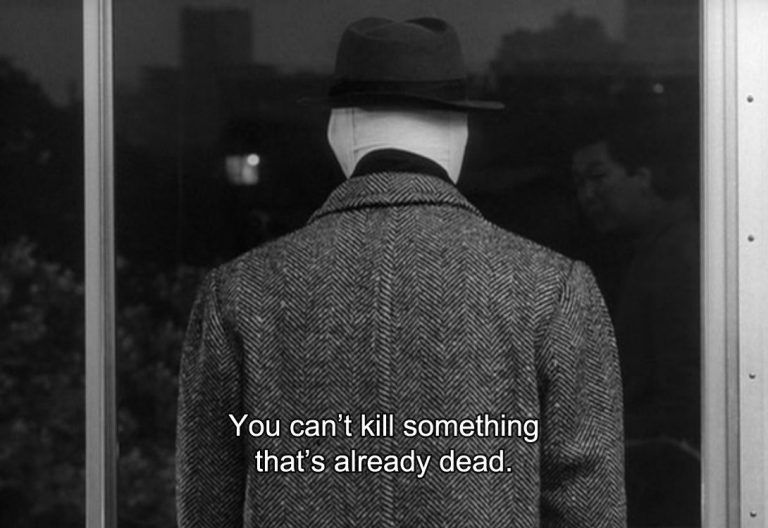

Keeping PT Anderson in mind here, Doc Sportello in Inherent Vice is a silly buffoon, although he’s likely doomed from the start given the brutal incoherency of the source Thomas Pynchon novel, which, in hindsight, I hoped that Anderson would have avoided in the first place. Sadly, Inherent Vice reminded me a bit of Ari Aster’s failed peripatetic effort with Phoenix in Beau is Afraid. Before this piece turns the corner and becomes more upbeat, one must lament Woody Allen’s moribund Irrational Man, where a teaspoon of self-intoxicating murder mixed with a teaspoon of faux philosophical meandering adds up to no more than a hollow recipe. It’s stunning that heavyweights PTA and Allen could not have done a better job grooming such a talent.

On the other hand, in his Gus Van Sant 2018 encore, Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot (as we will fulfill our due diligence below by returning to his vintage breakout in 1995’s To Die For), Phoenix plays a sympathetic, artistic and wheelchair-bound alcoholic who’s trying to resurrect his life, but neither with undue fan fair nor any coerced extraction of pity. Similarly, there is a refreshing blast of normalcy in C’mon C’mon, even if the film itself is ho-hum. Rather than crafting a top ten list or any facsimile thereof, it seems most reasonable to pose the following question: Are there specific, identifiable threads to help us chronicle more memorable cinematic achievements?

Unlike Phoenix, who has had to keep harnessing his special chameleonic abilities to remain viable, please note that others in the E & O space have had gimmicky headwinds, such as the signature look, which creates immediate connectivity with his filmgoers. To illustrate, the sprawling resume of Christopher Walken … he of the (sometimes spiky) bouffant, robotically fixed gaze, and haltingly cadenced Queens accent that has launched ten-thousand imitators … is much more compact than at first blush.

Once the persona was successfully launched as Duane (Diane Keaton’s brother in Annie Hall), the rest is history. This was a pre-packaged roadshow, where Walken simply played Walken. Some of his films were better, and other films were worse. Ditto for Robert Altman’s beanstalk muse Shelley Duvall (Brewster McCloud, 3 Women, Popeye, and Nashville). The stage was set as soon as pencil-limbed, toothy, bug-eyed Duvall hit us with her soft Texas twang. To think of it, tall man Jeff Goldblum was like a dude version of Duvall (with his bulging eyes, too), but he was more accessible to broader-based audiences than Shelley Duvall.

Phoenix’s absence of relatively consistent directorial oversight, which, in fairness to him, has withered away into extinction, prevents easy generalizations about a portfolio that has splintered into numerous directions. As a striking counterexample, the special bond between Martin Scorsese and Robert DeNiro has meticulously crafted hyper-intense, sometimes unhinged characters, each of whom has its own special lemon twist. Yet, their overall mission was not to create their own collectors’ set of wacky antihero variants only (whether it be Johnny Boy in Mean Streets, Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver, or Rupert Pupkin in The King of Comedy), but rather to keep pushing forward into new frontiers. Like virtually all others, Phoenix has not had the gift of such a secret sauce.

As we pry open the vault of his zig-zagging body of work in search of masterful performances, let us first visit the fictional New Hampshire village of Little Hope back in Gus Van Sant’s 1995 satirical black comedy To Die For. Predicated largely upon the actual Pamela Smart saga of a teacher who gets one of her students to murder her husband, enter Suzanne Stone (Nicole Kidman), a bizarrely obsessed media career wannabe who takes a withdrawn, goofy, faintly smirking, and masturbatory (over Suzanne) high-school kid Jimmy Emmett (Phoenix) under her wing, and gets him to do the evil deed.

The premise is chilling precisely because this is not your frankly worn-out, troubled-teen-coming-of-age storyline: It is a novel blueprint for tracking the arc of exploitative sexual fantasy. It also lays the foundation for the next twenty-five-plus years of Joaquin Phoenix’s performance art. Although the recent cinematic anthology of eccentricities has been typically forged through a male-dominated prism of screenplays and directors, we had better not forget that an equally adept chameleon, Kidman, makes this all happen. It is the complementarity of his visiting school project mentor, Ms. Stone, who lights the fire.

In getting back to Phoenix, shortly after To Die For, he was already beginning to traipse all over the map in various small films until two films in 2000 would be significant on different fronts, although both were related to him cutting his teeth in combat and crime-related fare. First, Gladiator would introduce him to additional mainstream viewers via director Ridley Scott. Furthermore, The Yards would mark his first collaboration with director James Gray. His stock would be on the rise as he headlined the Johnny Cash biopic Walk the Line by 2005, where he hit all the right notes, quite literally, as both he and co-star Reese Witherspoon (as June Carter) sang without dubbing. It was a solid, workmanlike outing, with just enough addiction-fueled destructive rage to keep the casting Rolodex’s warm.

In any case, Phoenix would return to work with Ridley Scott in 2023’s Napoleon with a performance that one might characterize as a hybrid between Scott’s usual attentiveness to spectacle and the subdued E & O of a mastermind warrior. Having zeroed in on the latter, I had some uneasy praise for this film since I tried to appreciate what seemed to be this dual construct. Beginning his relationship with James Gray holds much more personal interest since Gray was trying to carve out his niche in the New York City immigrant experience. Whereas The Yards and the subsequent 2007 We Own the Night are tales of urban tribalism where blood loyalty rules the roost, something remarkable happened the following year.

In 2008, James Gray discovered his inner softie with Two Lovers. On my calendar, this is where Joaquin Phoenix was born if we are granted some temporary amnesia regarding To Die For. Please imagine (even if with some expected difficulty) a story about Brooklyn Jews without the baggage of mile-deep craters bubbling over with neuroses and insecurities. Leonard Kraditor (Phoenix) is a twenty-something young man living at home who is bent-but-not-broken from a recent demonizing fiancé break-up. Israeli actor Moni Moshonov plays the dad, and Isabella Rossellini plays Mom, Ruth, whose generically ethnic accents fit the bill perfectly. Rossellini gives us a way overdue Jewish Mother aesthetic that is both calm and cleansed of stereotypical toxins.

The Kraditors are hardworking, unpretentious, and decent folk who are fully on board as Team Leonard. The plot revolves around Leonard’s conflicted relationship with a loopy but manipulative Manhattanite, Michelle (Gwyneth Paltrow), and the uber-nurturing, trustworthy daughter (Sandra, played by Vinessa Shaw) of the Kraditors’ friends, the Cohens. The remarkable core of this film hinges upon how Leonard seems so fragile and lost at the same time that he is intimately involved with both Michelle and Sandra. How this triangle plays out is far less noteworthy than the gentle back-and-forth rhythms of Leonard’s attempts to stabilize his life and become a mensch.

There was a mixed bag five years later in 2013: Gray and Phoenix would again collaborate on The Immigrant, with another familiar-looking chapter. Sadly, the script is so flaccid and regressive that the titular, off-the-boat Marion Cotillard and New York hustler Phoenix are never able to overcome it. Nevertheless, writer/director Spike Jonze would pick up the slack in continuing this same fragile, gentle journey in his film Her, but under completely different circumstances than Two Lovers. In this hold-on-to-your-sanity science fiction film, Leonard Kraditor has morphed into Theodore Twombly, a professional love letter writer who lives in a near-future, glass, concrete, and high-tech vision of LA.

While Theodore is undergoing a divorce from his wife, Katherine (played by Phoenix’s current real-life partner, Rooney Mara), he has failed at new love, except for Samantha (Scarlett Johansson), who is his operating system. Without belaboring the point that falling in love with a computer is more than a little bit strange, suffice it to say that Johansson’s smoldering, husky riffs, courtesy of Jonze’s top-shelf, Oscar-winning screenplay, makes all of us guys fall in line and fall in love to boot. As in Two Lovers, the loneliness is palpable even as he has found his e-soulmate. And to not ignore any percolating mommy issues, his friend Amy (the always classy Amy Adams) flashes the maternal twinkle that only the right type of friend is there to offer.

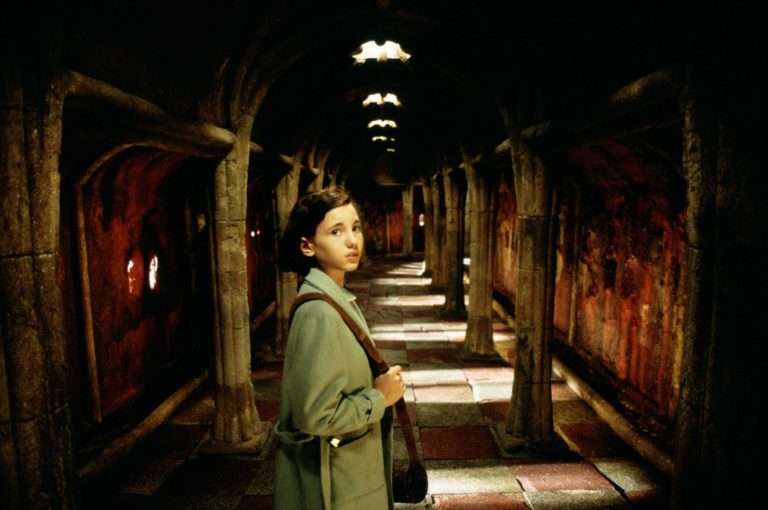

Five years later, enter Scottish director Lynne Ramsay, waving her most recent don’t be squeamish wand. You Were Never Really Here has artfully unified the various strands of previous performances. The plot centers around Joe, an Iraq War-traumatized, Travis Bickle-style night prowler who rescues teen girls from urban sex-trafficking rings using a hammer and duct tape. Ramsay cuts Phoenix loose and lets him do it all with incessant frontal staring, intermittent mumbling, and highly stylized camera work rife with flashback cuts. Who could envision that beefy Joe would soon become the wiry, taut Joker?

Ramsay’s calculated restraint allows no more than a minimal dose of explicit violence by alternatively relying upon implicit cues of pathos. She deftly toggles between various quirky but affectionate narratives: Singing a sweet tune to a dying hit, being tenderly avuncular with his main rescue victim (in a more cryptic, poignant turn than that of the stretched-out C’mon C’mon), and attending to his ongoing mommy saga.

Naturally, he lives at home with Mom, likely as part of some unwritten E & O male ritual, and the film’s most spectacular visual has to be the submersion scene when he buries his mother in a lake. She’s been murdered by those involved in the sex trafficking operation, and, while embracing her, the twosome sinks slowly, with rocks in his suitcoat, as he is attempting suicide, but then he unloads the rocks and floats alone back up to the surface. Did I forget to mention that Two Lovers has an opening near-suicide submersion scene?

Now we know for sure … Joaquin has the goods.