Sidney Lumet was one of the most important American directors to ever live. Evident through his immense filmography, he was a key director of dramas and thrillers throughout a number of decades, particularly in the ‘70s with regarded classics such as Network, Serpico, and Dog Day Afternoon – this series will cover some of his lesser known directorial efforts that perhaps should be as esteemed and as discussed as these works.

Read other entries in this series: The Pawnbroker, Fail-Safe, The Hill, The Anderson Tapes, The Offence

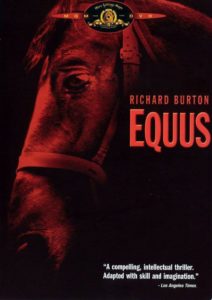

In the midst of the ‘70s, when Lumet was dropping some of his most well-regarded films such as Serpico, Dog Day Afternoon, Network, and his own adaptation of Murder on the Orient Express, he also released Equus, which was somewhat favourably received at the time, but has since been overshadowed by his other masterpieces. It may be easy to see why, given how indigestibly harrowing a film like this is, but it remains an emotionally traumatic and dramatically overpowering highlight of not just this illustrious director’s career, but of all of cinema’s history.

In the midst of the ‘70s, when Lumet was dropping some of his most well-regarded films such as Serpico, Dog Day Afternoon, Network, and his own adaptation of Murder on the Orient Express, he also released Equus, which was somewhat favourably received at the time, but has since been overshadowed by his other masterpieces. It may be easy to see why, given how indigestibly harrowing a film like this is, but it remains an emotionally traumatic and dramatically overpowering highlight of not just this illustrious director’s career, but of all of cinema’s history.

Based on the fairly infamous stage-play, child psychologist Martin (Richard Burton) is assigned a rather difficult case with 17 year old Alan (Peter Firth), who has recently blinded six horses at a stable he occasionally worked at. Although he initially seems like a hard seal to crack, Martin works inquisitively to try and pry him open and discover what lead up to such an attack.

Alan offers a barter system for Martin’s shrink work, having the psychologist answer every question that he asks of the patient, which seems to uncover even more troubling matters from Martin than Alan. But as Martin begins to successfully keep Alan elaborating on his unusual fascination with horses, he begins to realise the kind of tortured passion that Alan has that he hasn’t.

Similarly to The Offence, our guiding “protagonist” is in a position of defeating evil, but this character is soon revealed to be as much a part of this evil than their detained counterpart. Lumet has taken another close examination of the hypocrisies of the professionals in the bureaucratic system, when they see themselves in the disturbed folks they’re treating, as if they’re looking into a mirror – or for Martin, an inversed mirror that shows a disturbed, but liberated mutation of his own mutated self.

Equus really is a companion piece to The Offence, sharing its unambiguously dark treatment of its deeply troubled subject matter. Although Lumet’s other directorial work in the ‘70s dealt with rather dark subject matter, like Dog Day Afternoon and Network, there was a satirical slant to them to soften their edge. After venturing into these reasonably tough films (that have ended up as masterpieces), Lumet returned to his strength as a filmmaker who pulled no punches with his upsetting exposés of the darker qualities of humanity.

Also similarly to The Offence, Equus was based on a stage-play, and was adapted into this film by its own playwright, Peter Schaffer. He has crafted, for a character study, one of the finest screenplays ever. Martin’s dialogue, particularly his theatrical straight-to-camera monologues, are absolutely permeated with a hoity-toity well-read pretention that sometimes alludes to the mundanity of his life in fancily worded and Greek mythology-referencing analogies.

The acting from Burton and Firth (who had honed his performance from numerous runs of the play) is fierce, precise, and equally anguished. They bring to life the fiery character-focused dialogue-based screenplay, with Burton switching between barely contained frustration and agonizing stoicism, and Firth flirting between vulnerability and an assured power.

Over the course of two and a half hours, Equus delves further and further into the passion of Alan and the pain of Martin, and how these dual feelings overlap and interweave. Their back-and-forths in very lengthy psychiatry scenes become more and more wordy as Martin increases his success in breaking into Alan’s history and psyche, which unveil his impassioned, yet disturbing love of horses, which Lumet doesn’t shy away from portraying.

The film was released to mixed reviews, with many film critics comparing the film to the rather well known stage production. Like The Offence, it’s since been overshadowed by Lumet’s other films of the ‘70s, but I’d highly recommend it for those who can brace the dark, depressing, depraved world Lumet conjures that feels so devoid of hope. I’ve seen a few psychiatrist-treats-troubled-young-man films before, but none evolve as spectacularly as this one does.

![The Pirates: The Last Royal Treasure [2022] Netflix Review: Rehashed Pirate Comedy Film That Can be Skipped](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/The-Pirates-The-Last-Royal-Treasure-2-768x512.jpg)

![In the Tall Grass Netflix [2019] Review: One for the Stephen King purists only](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/In-The-Tall-Grass-Netflix-768x323.jpg)