“The important thing is not to be cured, but to live with one’s ailments.”

-Ferdinando Galiani

Neeraj Ghaywan’s debut feature ‘Masaan‘, a film about characters caught in between the cycle of suffering and salvation, captures the existential dilemma of the aforementioned statement. While the screenplay by Varun Grover carries an air of poetic-realism, the film’s mise-en-scéne and other filmic elements such as sound, cinematography, and even the casting choices, help amplify the film’s major themes.

Mise-en-scéne, a term that originated in theatre refers to “staging a scene through the artful arrangement of actors, scenery, lighting, and props”. In simpler terms, mise-en-scéne refers to the way filmmakers utilize several tools (such as cinematography, production design, and costumes) to enhance the thematic concerns of the film. A tale of characters affected by different calamities, ‘Masaan‘ thematically raises questions of suffering, pain, and redemption. Ghaywan’s skillful use of these filmic tools at his disposal helps in not just artfully arranging all the components, but also in subtly exploring the major theme behind this existential masterpiece.

Set in Varanasi, Masaan tells the story of three separate individuals whose sufferings entwine with the metaphor that their city has come to describe. The holy city of Varanasi – by the river Ganges has a mythical status in the country where numerous sinners flock to seek moksha or a release from the cycle of rebirth (and thus worldly pain) while also offering a divine promise of salvation to the ones who visits, resides or prays there. The title ‘Masaan’ refers to the burial grounds emblematic of the place where the soul can finally attain freedom from the cage of the body. A place of both ‘burning’ and ‘salvation’, the setting is central to the film and its ambivalence is beautifully captured.

But while scenic and picturesque, the film does not fall into the trap of exoticizing the city. Ghaywan in an interview stated that he did not want to tell the story from an outsider’s lens: “…the intention was to tell the story from an internal viewpoint”. Hence, the film does not begin with a montage of the city’s humdrum life or a landscape shot of the temples and ghats (as is usually the case to depict Varanasi in documentaries or in other mainstream films, for instance, Raanjhana (2013)).

Also Related to Masaan – The Reincarnation Of Indian Cinema

On the contrary, the film opens with Richa Chadha’s character watching pornography in her room, which paradoxically eliminates any essence of ‘holiness’ which the viewers might have come to expect. The middle-class setting of her place is further highlighted in the next scene. As Devi leaves her house, a man in his undershirt brushing his teeth from the neighboring household emerges, conveying the intrusion and lack of privacy present in her life.

Similarly, the father of the second protagonist, Deepak (Vicky Kaushal) urges his son to get a job as soon as possible, “Jitna jaldi nikal jao utna aacha hai…nahi toh tohre zindagi murda phookat phookat yahi khatam ho jai” (The sooner you get out of here the better. Otherwise your life will be exhausted in torching the corpses). The small town is thus far from idealized as both the protagonists find themselves trapped in the rigid setup. The stifling nature of the place is accentuated for both of them owing to their gender and caste respectively.

Deepak’s simplicity of character and lifestyle (perhaps governed by both his caste and class) is established right from the initial scenes when we first meet him. As he follows his friend who is about to propose to a girl, the sharp contrast is conspicuous in the way both of them have dressed. His friend has his hair dyed brown, wears a red shirt and goggles. His shoddy-Romeo like figure is further highlighted as he holds a teddy-bear, covered in sparkly wrapping paper; while Deepak is simply dressed (establishing him as naïve and innocent or “buddhu”, as Shaalu later calls him.)

The brilliant use of mise-en-scéne is further exemplified during Deepak and Shaalu’s courtship. Shaalu is introduced beside a chaat shop, standing with her friend (her face remains hidden by her hair). She is heard telling the vendor to add more spices and garlic chutney to her snack. Her vivacity is further elaborated by the bright clothes she wears and the books she reads. In one scene, as she navigates a bookshop with Deepak, she glances through a book by Faiz Ahmad Faiz (the patron saint of romantic verses) and soon picks up the copy of Raag Darbari and a book of poetry. Her passion for music and poetry is reflected in the shayaris she narrates to Deepak on phone calls, lifted straight out of the works of Bashir Badra and Ghalib, whom she reads.

Similar to Masaan – The 25 Finest Hindi Films Of The Decade (2010s)

Their pangs of first love are explored in a montage like sequence in the film. The song “Tu Kisi Rail Si Guzarti Hai” (Grover’s spin-off of Dushyant Kumar’s poem) plays, as Deepak and Shaalu steal glances during the Durga-Pooja fair. Suddenly, the scene cuts to Deepak taking a printout of Shaalu’s Facebook profile and admiring it in the solitude of his bedroom. This short-scene however also has great thematic concerns, as it highlights the way technology breaks through barriers of caste and gender. The film opens with Devi gazing at pornography on her desktop thereby exercising her sexuality; while Deepak befriends Shaalu via Facebook.

Further, the use of sound amplifies the romantic life Deepak finds himself in. As they make their way to Sangam, where both of them experience their first kiss, the song “Gazab Ka Hai Ye Dinn” from the Aamir Khan starer Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak (1988) plays in the background, becoming a non-diegetic element of the film. The use of the song serves two purposes: firstly it contributes to the dreamy mood which Deepak and Shaalu are experiencing, a mood further heightened by using the 1990’s Bollywood music. Secondly, the use of music from a film that ends in tragedy (QSQT), it also foreshadows some sinister outcome in Deepak’s own relationship.

Masaan is also a Part of – 10 Best Hindi Films of the Decade (2010s)

As discussed above, the film establishes Shaalu as a starry-eyed romantic individual, who is soon about to be exhumed in the harsh flames of life. Further, the brilliant casting and performance of Shweta Tripathi, who the viewers might have best remembered from the Disney show Kya ‘Mast’ Hai Life (How Cool Is Life), add a meta-textual presence to the film. Life in Masaan is not at all ‘mast’ (cool) and is far removed from any Disney utopia: romance and fantastical notions have no place here. Soon, after their meeting at Sangam, Shaalu leaves for Badrinath with her family and dies in an accident. The use of a song from a tragic film (QSQT) thus forecasts the tragic outcome of Deepak’s very own romance.

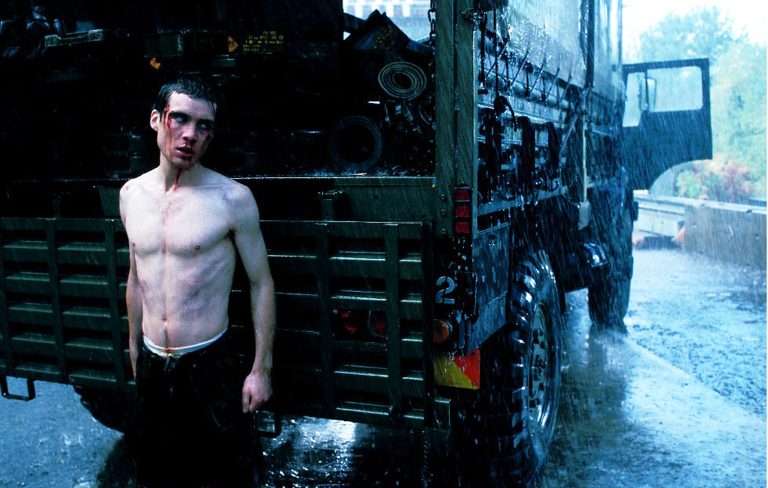

The turning event of the film, where Shaalu’s dead body is discovered by Deepak in one of his monotonous routines, is hauntingly filmed. As Deepak (numbed and shocked) watches flames engulf his beloved, the sparks from the funeral pyre prowl over the entire frame, rendering Deepak’s face almost blurry and invisible.

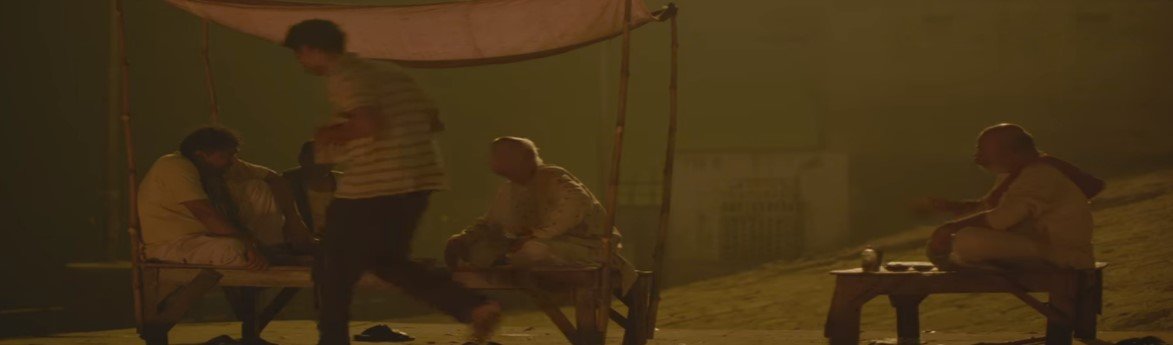

Caste is an important theme in the film and is subtly explored. In a sequence, where Deepak’s father (who is from the Dom community) is enjoying a drink with others near the crematorium, a Brahmin man is seen sitting with them. His stool on which he is eating his meal is visibly separated from the khat on which others are sitting. The film showcases how the practice of untouchability, rooted in the caste system continues to plague India, albeit in a more concealed form.

Similarly, the social standings of the two lovers: Deepak and Shaalu is made explicit via focusing on their background, as they speak on their phones. Shaalu’s house is located in a visibly upper-middle-class setup, while Deepak’s dwelling is in the crematorium itself. Due to this, Deepak hesitates from telling Shaalu about his residence and evades the topic throughout the day. It is only during the dark, when night renders an invisible cover from intrusive eyes, that Deepak bursts out about his social origins, leaving Shaalu mute and shocked by his otherwise-calm behavior.

The blocking of the actors is made use of brilliantly. Ghaywan’s apt use of camera and positioning of his actors leads to the creation of one of the most iconic scenes in modern Hindi cinema. Numbed by Shaalu’s death, Deepak is plunged into inconsolable grief and is bewildered at the randomness with which the hands of fate work.

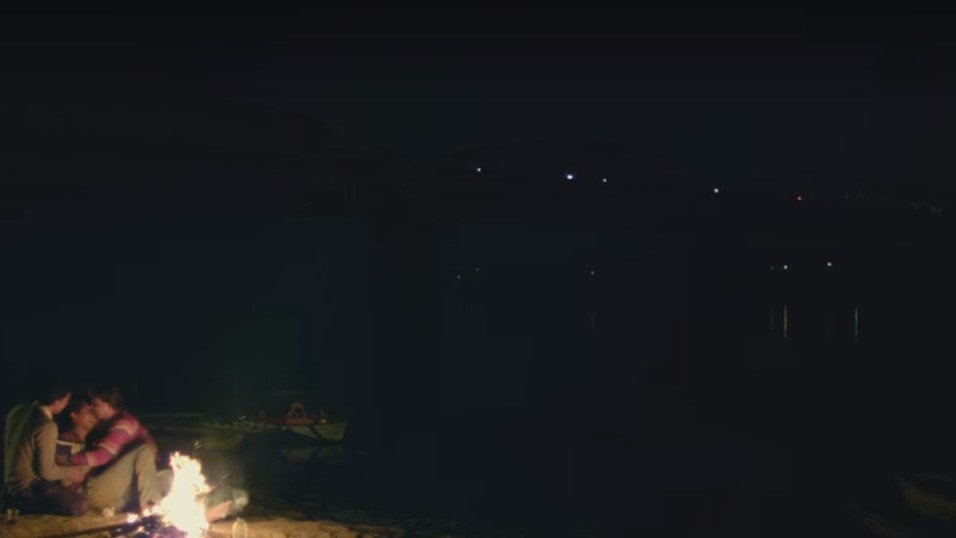

The scene is set around a bonfire, where a hazy Deepak is sitting with his friends, trying to exorcise his pain by drinking. Initially, as Deepak is speaking, there are three cuts in total to reveal the reactions of his friends. But as inebriation sets in and Deepak’s grief surfaces, the camera comes to a still focusing solely on Deepak, sitting alone, musing on the arbitrary nature of life. The take is a one-shot without any cut. The natural light from the fire adds to the gritty and realistic nature of the scene.

It is only when he has uttered the anguished cry symptomatic of the existential man, “Ye Dukh Kahe Khatam Nahi Hota Hai Be” (Why Does This Grief Never Ends?), then the other actors, portraying Deepak’s friends, come out into the frame, hugging and consoling him.

Also, Read – Top 15 Hindi Films of 2016

Traditionally in films (especially romance dramas), bonfires or fireplace usually anticipate a scene of sexual lovemaking (remember the campfire scene in Brokeback Mountain (2005), the brilliant exchange between the leads in the recent A Portrait of a Lady on Fire (2019), the iconic romantic sequence in the song “Roop Tera Mastana” from Aradhna (1969) or our very own infamous ‘haseen-dard’ of Fardeen Khan’s Prem Aagan (1998) to include a dishonorable mention). Ghaywan subverts the trope in Masaan to convert it into a scene of male-bonding while simultaneously allowing a common jilted lover to lash out at the forces of the Universe. As the scene ends, the camera withdraws to a long shot, showing the undisturbed train moving on–a larger symbol of the universe’s indifference to man’s suffering.

Another subtle use of blocking and character positioning can be seen in one of the initial scenes in Masaan. As Devi and her lover, Piyush make their way to the hotel, they check in with the receptionist. The receptionist is positioned as such that he hides the portrait behind him. It is only when he moves a little that we get a glimpse of the idol of Lord Ganesha behind. The receptionist stealthily eyes both of the lovers which possibly hints at his tipping the police about them. Thus, Ghaywan’s positioning of the actor (the receptionist) as he conceals the pious statue behind him anticipates the sacrilege that he is about to commit.

Both Devi and Deepak’s character arcs are completed mainly through poetic film techniques, with little use of dialogue. Tired of even his grief, Deepak throws away Shaalu’s ring in the river. Realizing that he cannot let go of her, Deepak jumps into the water to retrieve the ring but fails to find it. As he struggles in vain, a beautiful lotus floats by. Deepak admires it in awe but instead of holding it, he lets it go: realizing it is time to move on. Seeing the lotus fade away into the distance, Deepak has his own moment of epiphany. A lot is communicated without the aid of any dialogues here. The song “Mann Kasturi Re”, an allegory of a mind that cannot find peace, fits in perfectly with the sequence.

A similar use of silence and still-camera is used in Devi’s attempt at reconciliation. As Devi goes to Piyush’s house at an attempt to pacify his parents, the entire scene is one long shot, where the camera remains stationary outside the house. It is Devi’s very own chance at redemption and thus we are not made to intrude upon this private moment. Devi enters the house to meet Piyush’s father while the camera remains still. In the background, a piercing shout followed by the sound of glass breaking is heard: implying that the reconciliation has failed. Ghaywan condenses a lot in a single shot without allowing our eyes to witness the incident.

The final scene of the film merges the two storylines into one. Both, Deepak and Devi are sitting beside the same ghat, albeit separated from each other. As Devi is seen crying over her failed attempt to reconcile with the parents of her dead lover, Deepak moves into the frame, offering her a bottle of water. Two people with a similar tragedy are brought together. A man belonging to a socially disenfranchised caste and a woman born in a Brahmin family. But the conundrums of life and death, the trauma and its aftermath appear to be the same for both of them.

Their struggles are different and yet the same. Masaan thus sets a new equation of looking and understanding the marginal identities, by transcending the quintessential way of looking at human beings as merely a sum of their constructed identities, thereby conveying the profound message that despite our differences, the thread of pain is common to all. We should paddle together in life and not remain oblivious to the sufferings of fellow human beings. The boatmen asks them to come and sail towards Sangam, a ride which is thought to release sinners from the suffering of this world. The film ends with both of them in a single boat, riding in the river of life towards salvation, as the sun gleams in the background.

Masaan makes brilliant use of the filmic mediums to portray universal human suffering, through two individualized tragedies. The use of lighting, camera angles, blocking, and music add to the ethereal experience of the film. As the film ends, both Devi and Deepak realize that the tragedies of life offer no catharsis. The sun gleaming in the background illuminates for both of the individuals, the existential truth of life as walking chaos of endurance. Life is a riddle without an answer. The heart will never get its closure, or in more poetic words, “Mann Kasturi jag dasturi/ Baat Huyi Na Poori Re.”

Masaan Notes/References:

1. The definition of mise-en-scéne as quoted in the book Film: A Critical Introduction by Maria Pramaggiore and Tom Wallis.

2. The interview of Neeraj Ghaywan by Nandini Ramnath, published at Scroll.

3. This essay owes a lot to the insights delivered on different films by Dr. Rittvika Singh in her classrooms. However, this idea is specifically her unique observation, delivered in the classes on mise-en-scéne. Hence, the separate reference.