The Problematic Representation of Dalits in Bollywood’s “Essential” Films: Many casual Bollywood viewers today vaguely remember B.R. Ambedkar’s legacy as a social reformer, and their own constitutional rights learned in high school civic studies. In reality, though, both are mainly talking points for India’s privileged classes and how they collectively look at mainstream social films that the industry has been churning out at an increasing pace in recent times.

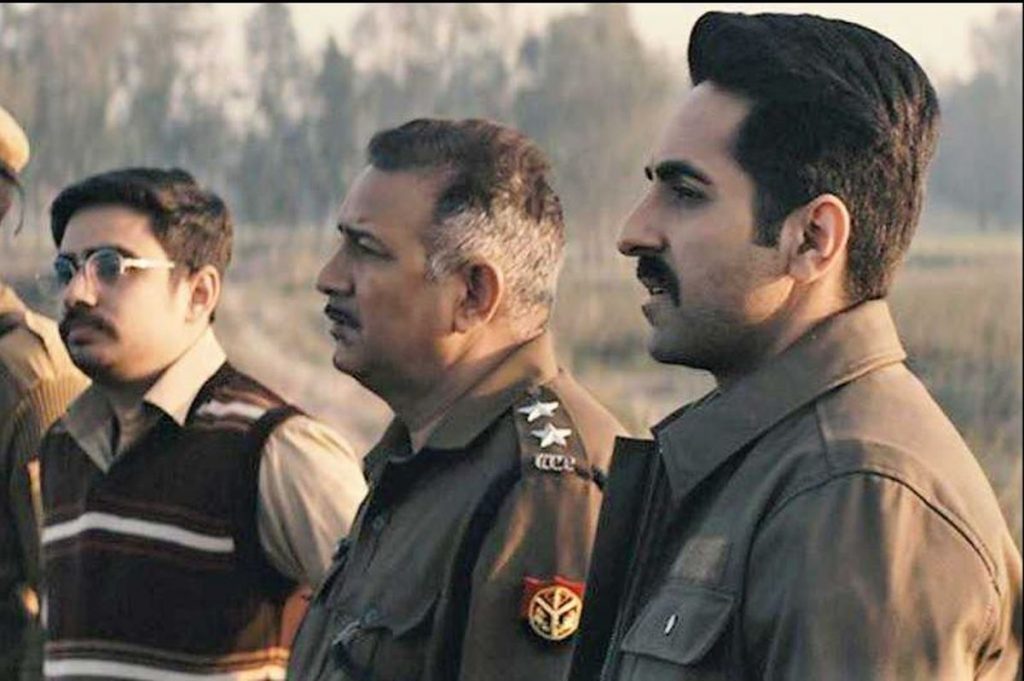

“Article 15”, Anubhav Sinha’s first collaboration with Ayushmann Khurrana was about an upper-caste cop investigating a crime against Dalit people in a rural village. While it has been praised for tackling caste-based violence head-on – a topic usually relegated to art house or indie films – it was also criticized for falling into the “Brahmin saviour complex” narrative that’s since long has become a trait of such films.

The ‘Savarna Saviour Complex’ (much like the term ‘White Saviour Complex’) implies to the idea that people who benefit from such privilege are wanting to help those in underserved communities for their own benefit more than that of the communities. “This is not just about justice. It is about having a big emotional experience that validates privilege,” said Teju Cole in his seven-part Tweet that coined the term (@tejucole). This concept manifests itself in many spaces including entertainment, media, disaster relief, education, policy, politics, law enforcement, and more. It serves as a valve for releasing the unbearable pressures that build in a system built on pillage. The ‘lower’ class is thus assumed to lack the capacity to seek change and is thus evicted from a historical agency. It undermines thousands of years of victimization and feeds into the stigmatization of beneficiaries.

Even when movies such as “Sujata” and “Aarakshan” addressed caste, Dalit protagonists were either shown as helpless or dependant on the munificence of the widely upper-caste society. Our film industry in itself is widely upper caste. Only a handful of fraternity members have self-identified as belonging to a lower caste. Given this context, most Bollywood films could be considered as suffering from a Brahmin saviour complex – where the usually fair-skinned savarna hero saves the day. Dalit activists and writers back in the day had criticized “Article 15” for failing to meaningfully challenge India’s social hegemony. They argue that it’s not really a film for Dalit people, who are well aware of daily oppression. And Dalits were not represented in the cast other than a real-life sewer cleaner in a bit role.

From a Dalit perspective, filmmakers such as Neeraj Ghaywan and Nagraj Manjule have consistently been churning out quality cinema with a much smaller budget. Interviews of these filmmakers shed light on how deep-rooted casteism is in Indian cinema and how challenging it is for them to bring out Dalit narratives to their audiences. So, there’s some hope going forward. But the larger question here is, what expectations could one have from a Bollywood film to get audiences to reconsider their own prejudice? After all, the most common accusation and view against Dalit people is that they already benefit from various affirmative action measures in place.

The vacuum created by the absence of any response or resistance from the Dalit characters elaborates that the oppressed themselves cannot speak and thus, are spoken for. Even when the films for the most part are made to serve a good larger and meaningful purpose, one can’t help but keep noticing this reoccurring trait. Having denied Dalits their voice, the non-Dalits have become self-appointed spokespeople of the Dalits throughout the span of industry. Such depiction in Bollywood has resulted in the misrepresentation and misappropriation of Dalits’ experiences. That’s why whenever a low-scale film actually gets the representation right, it’s praised massively.

The continuous stereotypical representation of submissive, dark-skinned, shabby, and under-confident individuals continues in the films and has only grown more evident. There is a repeated portrayal of men and women being outcasted. Thus, this leads to the reality of the marginalized being buried so much that it’s unable to move beyond an upper caste gaze.

The melodramatic representation of the ‘lower’ class through films such as “Acchut Kanya” ‘‘Sujata’’, ‘‘Lajja” and even “Swades” has obstructed the thoughtful representation of Dalit characters. So, the oppression of Dalits is not only material but cultural. This might be because who is behind the camera in these scenarios plays an important role in how effective the conveyance mechanism of the movies is. This is especially true in a country where the mainstream Hindi box office numbers are mainly driven by the Hindi-speaking belt; the upper caste paying audience would prefer to see the status quo of upper caste dominance maintained. Since every producer wants their film to make money, most of them create narratives that cater to the upper caste audiences, who pay to watch the movie.

Such linkages might have a relation with large cultural and political practices prevalent in the society. The cultural cluelessness of the protagonist makes him caste-blind. Most of these central characters are not just Brahminic, but urban Brahminic. Caste has since long become a medium to assert identity in Tamil films. However, in Hindi cinema, Dalit characters are continued to be sidelined. A lot of this attributes to how many people living in urban India and in the diaspora consider themselves truly casteless. Lately, it’s not just about Dalit characters’ representation on screen. The template of a young naive urban-man moving to a village and then installing sensitive notions about class and gender into the rural population there has become so overused, that mainstream filmmakers are now running out of ideas to tell essential stories obliquely.

The patriarchal struggle in Bollywood goes hand in hand with a saviour complex which usually gives cis-gender males the role of a ‘hero’, dubbed as a protagonist even in movies about women empowerment. Anubhav Sinha’s latest, “Anek” turns its gaze towards the Northeast, where the problem isn’t casteism, but a complete lack of acknowledgment of the people living there who continuously have been facing discrimination despite being equal citizens of the country. Although the film marked a step in a well-intended right direction, the screenplay muddled itself into ticking way too many ‘essential’ checkpoints.

The film, through its use of exposition-heavy voiceover and disjointed structure, comes across as being so arrogant in its otherwise convoluted storytelling, that it keeps talking down to its audience, by constantly telling us how unfortunate the state of the ‘NE’ is. Yet, it goes so far out in proving its point that it starts treating its audience as illiterate. It becomes interesting then to ask the question, to what extent is it possible to look at these ‘essential’ films from an objective lens? The possibility of this piece leaving you even more perplexed is quite high, but it’s through such a mindful discourse and dissection of how the industry works, that can we become conscious of how we perceive the films that come out of it. As filmmaker Shekhar Kapur (Bandit Queen, probably the best portrayal of casteism) declared on his blog in 2009, “All art can be a tool of social change,” further adding how cinema can question, but “is unlikely to give effective answers.”