Reading Writer (2021) through a Marxist Lens: How do you define a State? A-State (government) is an institution that has been created by the exploiting classes to maintain the status quo especially when it is in danger of being broken by the rebellion of exploited classes.

This is how Marxism defines the State and terms both the police and the armed forces as merely ‘instruments of the State apparatus’ ripping simultaneously almost every shred of romanticism that has come to accompany portrayals of cops and soldiers in mainstream Indian cinema. Almost every significant event in Indian history such as the acquittal of the owner of the Union Carbide Company in the Bhopal Gas Tragedy case to the recent shooting down of anti-Sterlite protestors at Tuticorin, the State has been unpardonably kind to the rich and the possessing classes regardless of the enormity of their crimes while being brutally harsh on the poor even if it is glaringly obvious that most of them belong to the side of the victim.

But let’s forget Marxism for a while and try to re-examine the nature of the army and the police force from a slightly different angle. Don’t these armed forces almost fully consist of people who usually don’t give a damn about shedding their lives for something which they intentionally or unwittingly believe? Why don’t anyone among us who think that policemen are mere ‘hooligans’ employed by the State even once try to muster levels of courage that approach those of theirs and shed our lives to what we really believe in? Why are we so much obsessed with survival and careerism all the time that we are willing to surrender anything from our pockets to make sure we live to see another day in this mad world of consumerism and cut-throat competition? Isn’t someone who is willing to shed his life for an ideal no matter how flawed or crooked it is, innately higher than the one who would do anything to merely save his life?

I was shocked to read a report in The Frontline in 2013 that every year at least 100 soldiers in our Indian Army commit suicide owing to terrible working conditions such as very few leaves, poor food and sanitation facilities, etc. The report also went on to add that most soldiers post their retirement do not get free and immediate access to proper medical facilities since private hospitals do not want to treat them for money that would be reimbursed to them only after months and months of follow-up with the Union Defence Ministry. A good number of soldiers even now suffer from chronic health issues only because of exposure to trauma, lack of sleep and prolonged absence from their families. But these health issues when they surface and become unmanageable without treatment, especially in the post-retirement phase of their lives, the State is only happy to ignore them and feed them to the whims of the ‘Market’. So how do we look at these hapless people who have only been treated as cannon fodder by their employer, the State in this case, in whom they had trusted all along their lives, blindly and willingly? Aren’t these people too an integral part of the working classes or for want of a better word, the exploited classes themselves? Isn’t it our duty as humanists or so-called progressivists to raise our voices for these people as well?

Also, Read – The 20 best India Movies of 2021

These are the questions that debutant director Franklin Jacob tries to raise in his fantastic 2021 Tamil film Writer (2021) produced by Pa Ranjith’s Neelam Productions. Writer, in my opinion, demands the attention of almost every single movie-buff in this country not only for addressing the aforementioned, rarely touched-upon issues that easily miss newspaper headlines but also for the way these issues have been so beautifully folded into the screenplay and allowed to play out so effectively on screen. Most Tamil movies that focus on messages remain unwittingly captive to the latter and play out on screen solely as message-dispensing machines losing all their characteristics of being a movie in the first place. ‘Writer’ effortlessly transcends the aforementioned curse of the message-movie genre and rightfully claims its place as one of the most important works in contemporary Indian Cinema.

***

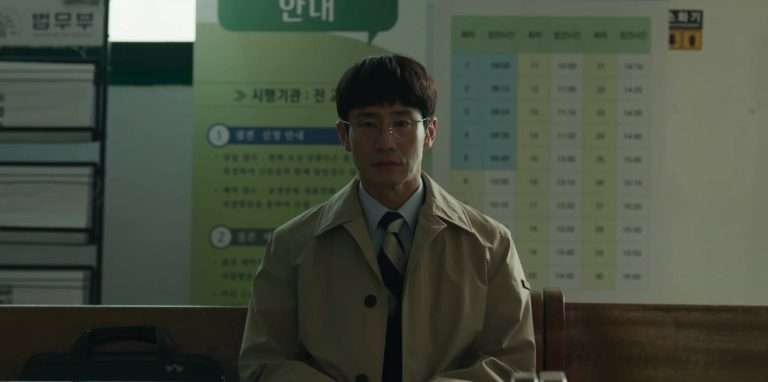

Thangaraj (a stupendous Samuthirakani) is a constable in the Tamil Nadu Police Force working in a rural police station and nearing his retirement age. He is shown as someone who has a slightly inflated sense of justice and wants to complete his career as someone who has never harmed the general, innocent public even once during his long, tumultuous years of service, something that most people employed in the police force simply wouldn’t be able to achieve. But the beauty of Thangaraj’s character lies in how Franklin successfully manages to specify or define correctly the exact ‘volume’ of his idealism. Thangaraj, we later come to know, is associated with the local Communist Party indirectly and has spent more than three decades trying to win the Government’s approval to allow the members of the police force to form a Union for themselves. He is fully aware of the travails that people in the lower ranks of the force undergo and his sense of justice smoulders whenever higher officials openly treat their subordinates in a very condescending manner. But he is no saviour who would grab the collar of his superior and demand the rights for his fellow colleagues nor is he a saint who would easily forgive their sins. In many ways, he could be called the most realistic rebel who clearly knows the boundaries of his freedom and is content to carry on with his struggle through strictly constitutional or legal means. He knows pretty well that the fight he has taken up shall jeopardize his career growth as a result of which he is happy to remain at where he has been condemned to, by the management -a ‘lowly’ Writer in the local Police Station even at the age of 58. But this commitment to a lofty cause interestingly does not in any way hinder the discharging of his daily duties as a cop. He is fully and sincerely dedicated to his profession even if he doesn’t like the consequences of it.

And the interesting shades of the character do not stop there. He is shown to be the husband of two women at the same time, one old and another young. He is portrayed as a person who couldn’t say no to his parents when they forced him to marry another lady when his first wife was found to be incapable of bearing children. Thangaraj bears this guilt with pain and brooding but both these women, on the other hand, have somehow made peace with their lives which in many ways reminds us of what has become the story of women in today’s semi-feudal, quasi-capitalist India. But this is exactly the place where a fascinating duality to the character surfaces- Thangaraj is shown as a typical male who would go on to marry two women at the same time and have relatively fewer qualms about directly or indirectly ‘oppressing’ both of them. But this ‘oppressor’ at home is in turn destined to face oppression at his workplace in an even more toxic and dictatorial environment where Thangaraj is harassed almost every day by his superior colleagues. In many ways, I could see this as the curse of the Indian male of today who has no guilt in subjugating the female at home while marching out of it and entering the workplace only to get subjugated in turn, by his capitalist employer. Despite so many emerging opportunities for women to get gainfully employed, our patriarchal society still expects most of the time, only men to take care of the bread-winning duties for the family which in my opinion are no less difficult compared to what women do in the kitchens and washrooms of their homes all day. If you ask me to put it more simply, I would say that- patriarchy spares none, not even men.

***

Coming back to the film, there is another story of another protagonist, Devakumar, a Dalit PhD student who is arrested unofficially and unjustly branded as a Naxalite. On the other hand, Singam who is transferred to Chennai as a punishment posting for his Union activities is entrusted with the job of keeping him in confinement. What Singam does unwittingly to help Devakumar ends up exacerbating the situation of the latter and what follows forms the rest of this compelling story.

***

Devakumar’s character as a hapless Dalit scholar, as film-maker Franklin mentions, is a direct reference to Jesus Himself who is forced to atone for the sins of someone else. Only towards the end, do we get to know that Devakumar too had been working to expose the ruthlessness of the Police Force in treating its own rank and file, a cause which is astonishingly similar to what Thangaraj has dedicated his entire life to. This coincidence also allows us to look at Thangaraj ‘s character in a completely new light as that of Judas who finally ended up betraying the Lord Himself.

But Franklin as he repeatedly mentions in his Deep Focus with Baradwaj Rangan does not in any way try to glorify a character or show him in a dramatic light, even if they are the victims in the story. Devakumar too is shown to be earning the righteous wrath of his brother’s wife (who reportedly played a big role in bringing him up) for not getting a job for himself and proceeding with his higher studies without giving a thought about the family’s insurmountable pecuniary difficulties. Devakumar’s character too is imbued with the same duality that marks Thangaraj’s characterization where his indirect oppression of his brother’s wife is more than compensated for by the oppression he faces at the hands of the ruthless establishment.

This level of sophistication that Franklin has achieved in sketching his main characters is not thankfully in any way demonstrated through pure exposition or showy film-making. Franklin allows the environment and atmosphere of his scenes to speak for themselves and what has to be conveyed through reams and reams of dialogue are simply made known to us within seconds in a few nicely conceived segues and brilliant sequences.

***

Tamil Cinema, post the arrival of Pa Ranjith has managed to shed many of its inherited, congealed characteristics to romanticize cops and the armed forces and specifically the last decade alone has witnessed the gradual movement of Tamil Cinema towards a radically Leftward political position. Beginning with Visaranai (2015) which was in my opinion an open Marxist indictment of the character of the State and its apparatus, followed by Jai Bhim and Karnan (both 2021) Tamil Cinema has come a long way from saluting policemen merely for the colour of their uniforms to looking at them with derision for being merely Bouncers employed by the usually, anti-poor State. Well-made propaganda mainstream movies such as these were no doubt gigantic steps in introducing the mass audiences to something that their traditional belief systems would not readily warm up to. And thanks to these radical filmmakers and incidents at Tuticorin and Sathankulam, we Tamils have to an extent constructed a healthy cynicism about the aims and intentions of the apparently ‘heroic’ cops who patrol our streets night and day.

Related to Writer (2021) – Review: Visaranai is a riveting and meaningful cinema

But the mere identification of the entire police apparatus with the oppressive character of the State itself is only one step in the right direction. If Marxism has taught me to look at human history as a long story of the great battle between the two opposing classes- the haves and the have-nots or the oppressing and the oppressor, it has done so only with an eye towards identifying the real problems of mankind and improving the lives of individuals. And when I say individuals, I am talking about the structural and functional units of mankind as a whole and every individual regardless of which class he belongs to is, after all, a human being in the first place. And as I have mentioned above, just like patriarchy, oppressive apparatuses such as the State like to spare virtually no one, not even members of its own camp. And this form of recursive oppression one may be able to identify correctly as the basic working principle behind the creation of caste hierarchies and their accompanied exploitation that continues to fester the social fabric of India even today.

Franklin through Writer (2021), not only exposes the crimes that an apparently virtuous police force is capable of perpetrating in a so-called transparent democracy such as India but also curiously calls for the attention of the masses towards what is happening on the usually opaque inside of the police force. Pa Ranjith, Vetrimaran and Mari Selvaraj through their path-breaking films had the guts to confront something like an assembled column of policemen waiting for orders to shoot at them. Just like how Lenin’s successful October Revolution in Russia against the Tsarist State rode heavily on the prospects of soldiers belonging to the Tsar’s army joining his side, the success of Franklin’s Writer lies not only in his courage to face the intimidating enemy. It lies in his Leninist bravura to offer them a handshake and boldly invite them to switch sides.

“Theemai Enge thedi theerpom vaa!!” (Exploitation wherever it is, let us go on to obliterate it!!)

![Kavaludaari [2019] Review – A layered Murder Mystery from the writer of Andhadhun](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Kavaludaari-2019-High-On-Films-768x430.jpeg)

![Touch [2021] Review – Cultural tension arise in sensual, flawed directorial debut](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Touch-1-highonfilms-768x325.jpg)

![The Billion Dollar Code [2021] Netflix Review – A Story About Two Friends That Calls Out Google’s Hypocrisy](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/TheBillionDollarCode_01-768x383.jpg)