Alfred Hitchcock looms large over the landscape of cinema like a portly specter, his influence casting long shadows that stretch far beyond the confines of the thriller genre he so masterfully defined. From his early days in the British film industry to his reign as Hollywood’s “Master of Suspense,” Hitchcock’s career spanned six decades and two continents, leaving an indelible mark on the art of filmmaking that resonates to this day.

Hitchcock’s journey began in the silent era, where he honed his visual storytelling skills, learning to convey complex emotions and nail-biting tension without the crutch of spoken dialogue. This early training would serve him well throughout his career, as he became renowned for his ability to manipulate audience emotions through pure cinematic language – a raised eyebrow, a lingering camera pan, or a perfectly timed cut could speak volumes in a Hitchcock film.

The director’s visual style was as distinctive as his storytelling. Hitchcock’s camera was never a passive observer; it was an active participant in the narrative, guiding the viewer’s eye and manipulating their emotions with surgical precision. His famous “Hitchcock zoom” effect, which simultaneously pushes in and pulls out the camera, became a cinematic shorthand for psychological distress.

Hitchcock drew inspiration from German Expressionist cinema, with its distorted perspectives and chiaroscuro lighting. His characters’ psychological depth owed a debt to Freudian psychoanalysis, which was all the rage in mid-century America. Even the world of fine art found its way into Hitchcock’s work, with paintings by Edward Hopper and Salvador Dalí informing the director’s visual compositions and surrealist dream sequences.

As we dive into the 20 best films of Hitchcock’s filmography, we’re not just examining a collection of excellent movies. We’re exploring the work of a cinematic alchemist who transformed our basest fears into pure gold. This master manipulator played audiences like a fiddle and left them begging for an encore. Enjoy!

20. Frenzy (1972)

The film that marked Hitchcock’s triumphant return to his native London after decades in Hollywood, “Frenzy” is a wickedly dark comedy wrapped in a gruesome thriller, proving that the aging director still had a few tricks up his sleeve. Set against the bustling backdrop of Covent Garden’s fruit and vegetable market, the film follows the gruesome exploits of a serial killer terrorizing London. Our antagonist is Richard Blaney (Jon Finch), a down-on-his-luck ex-RAF officer with a nasty temper and a penchant for the bottle. When his ex-wife Brenda (Barbara Leigh-Hunt) turns up dead – strangled with a necktie – all fingers point to Blaney. The real culprit, however, is Blaney’s jovial friend Bob Rusk (Barry Foster), a fruit merchant with a sinister secret.

Rusk, charming on the surface but psychopathic beneath, strangles women with his trademark necktie after raping them. As Blaney flees the law, desperately trying to clear his name, Rusk continues his murderous spree with chilling nonchalance. One of the film’s most memorable sequences occurs when Rusk lures Babs (Anna Massey), Blaney’s girlfriend, to her doom.

As the pair ascend the stairs to Rusk’s flat, the camera slowly retreats down the staircase and out onto the bustling street, leaving the audience to imagine the horror unfolding inside. While “Frenzy” may lack the polish of Hitchcock’s most celebrated works, it compensates with raw energy and daring, as the maestro paints a picture of a system more concerned with appearances than justice – from the ineffectual police force to the sensationalist media.

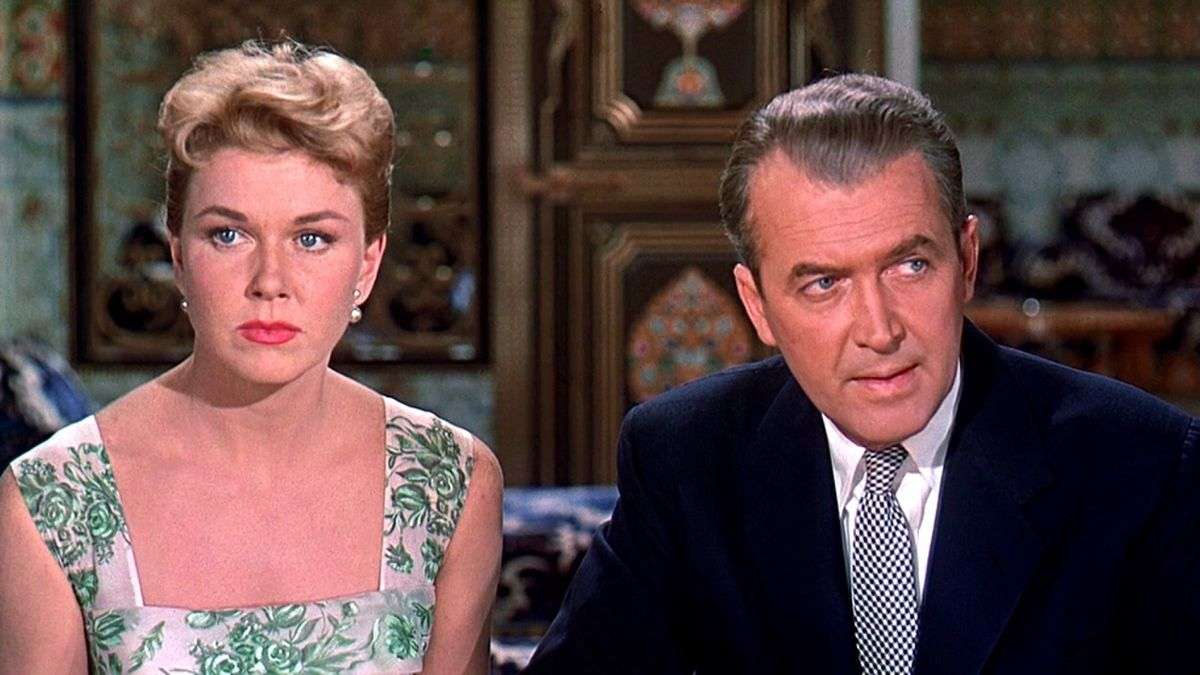

19. The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956)

Remaking his own 1934 film, Hitchcock’s “The Man Who Knew Too Much” is a technicolor spectacle shot in Morocco and London, weaving a thrilling tale of suspense, family drama, and international intrigue that keeps viewers on the edge of their seats from start to finish. As the film opens in sun-drenched Marrakesh, we meet the McKenna family: Dr. Ben McKenna (James Stewart), his wife Jo (Doris Day), a former singer, and their precocious son Hank (Christopher Olsen). Their idyllic vacation turns sinister when they befriend Louis Bernard (Daniel Gélin), a mysterious Frenchman who is not what he seems. As fate would have it, Bernard is (quite literally) stabbed in the back during a colorful marketplace scene.

With his dying breath, Bernard whispers a cryptic message to Ben about an assassination plot in London. Before the family can process this shocking turn of events, their son Hank is kidnapped by a shadowy organization that will stop at nothing to prevent the McKennas from sharing Bernard’s secret. Hitchcock makes full use of the exotic Moroccan locales, filling the frame with vibrant colors and bustling street scenes that contrast sharply with the more subdued, shadowy London settings.

His mastery, evident throughout the film, peaks during the iconic Royal Albert Hall assassination attempt sequence: the camera swoops and glides through the opulent concert hall, the swelling music perfectly synced with Jo’s growing panic as she spots the assassin. It’s a masterclass in building suspense through visuals and sound, culminating in Jo’s gut-wrenching scream that disrupts the performance and saves the intended victim.

18. Spellbound (1945)

A noir-tinged thriller set against the backdrop of a mental institution, “Spellbound” plumbs the depths of the human mind while keeping viewers biting their nails in anticipation. It opens at Green Manors, a psychiatric hospital in Vermont, where the arrival of the new director, Dr. Anthony Edwardes (Gregory Peck), sets hearts aflutter – particularly that of Dr. Constance Petersen (Ingrid Bergman), a brilliant but emotionally frigid psychoanalyst. However, it soon becomes apparent that all is not as it seems with the dashing Dr. Edwardes. His peculiar behavior – including a bizarre reaction to parallel lines and the color white – raises Dr. Petersen’s eyebrows.

Constance’s professional curiosity quickly blossoms into love, but her world is turned upside down when she discovers that “Dr. Edwardes” is an impostor suffering from amnesia. The real Edwardes has vanished, presumed murdered, and our amnesiac protagonist (whose real name is John Ballantyne) is the prime suspect. Convinced of John’s innocence, Constance embarks on a perilous journey to unlock his repressed memories and clear his name. The film’s visual style shifts seamlessly between the sterile, orderly world of the hospital and the chaotic, fragmented realm of John’s subconscious.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the famous dream sequence designed by Salvador Dalí. This surrealist interlude, with its giant eyes, misshapen wheels, and faceless figures, is a tour de force of psychological symbolism that pushes the boundaries of what was possible in 1940s Hollywood cinema. Hitchcock also challenges gender norms of the era by positioning Constance as the active, rational force driving the narrative forward, while John is often passive, emotional, and in need of saving.

Also Read: 10 Films To Watch If You Love Inception (2010)

17. The Wrong Man (1956)

“The Wrong Man” stands apart in Hitchcock’s oeuvre as a stark and unsettling dive into the nightmarish realm of mistaken identity. Based on the true story of Christopher Emmanuel Balestrero, this black-and-white docudrama eschews Hitchcock’s usual flair for the sensational, instead offering a grim, almost clinical examination of an innocent man’s descent into a Kafka-esque legal labyrinth.

The film opens with Hitchcock himself appearing on screen as a silhouette, solemnly informing viewers that “every word is true” in the movie. We’re then introduced to Christopher “Manny” Balestrero (Henry Fonda), a mild-mannered jazz bassist at the Stork Club in New York City. Manny’s life is unremarkable but content, and he shares it with his loving wife, Rose (Vera Miles), and their two young sons.

When financial pressures mount due to Rose’s dental needs, Manny visits a life insurance office to borrow against Rose’s policy. Here, fate deals Manny a cruel hand as the clerks at the office mistakenly identify him as the man who robbed them twice before. What follows is a harrowing spiral into a justice system that seems designed to presume guilt rather than innocence.

Hitchcock’s craft is a masterclass in restraint: gone are the swooping camera movements and stylized set pieces of his more famous works. Instead, we get a documentary-like approach, with stark lighting and claustrophobic framing that emphasize Manny’s growing sense of isolation and helplessness. The director’s use of subjective camera work is particularly effective, placing the viewer squarely in Manny’s shoes as he endures one indignity after another.

16. The 39 Steps (1935)

A rollicking spy thriller that set the template for many of Hitchcock’s later masterpieces, “The 39 Steps” is a British gem based on John Buchan’s 1915 novel of the same name. Richard Hannay (Robert Donat) is a Canadian visitor to London. He finds himself thrust into a web of intrigue when he meets Annabella Smith (Lucie Mannheim), a mysterious woman who claims to be a spy. After she’s murdered in his apartment, Hannay becomes both a suspect and a target, forced to flee to Scotland to unravel the mystery of “The 39 Steps” and clear his name. What follows is a breathless chase across the Scottish Highlands, with Hannay dodging both the police and a shadowy organization of spies.

Along the way, Hannay is reluctantly handcuffed– literally and figuratively – to Pamela (Madeleine Carroll), a blonde beauty who initially disbelieves his wild tale but gradually becomes his ally and love interest. The film moves at a breakneck speed, with each scene propelling the story forward while ratcheting up the tension. Yet Hitchcock never sacrifices character development for the plot, allowing moments of humor and romance to punctuate the suspense.

The camera work is dynamic and inventive, making full use of the Scottish landscapes. One famous scene where Hannay and Pamela hide from their pursuers in a misty glen is both visually striking and fraught with tension. Hitchcock’s use of shadows and silhouettes, particularly in the opening music hall scene and the climactic confrontation, adds a noir-ish element that enhances the film’s sense of mystery and danger.

15. Lifeboat (1944)

“Lifeboat” is a claustrophobic wartime thriller that proves the Master of Suspense could create heart-pounding tension even within the confines of a single small setting. Based on a novella by John Steinbeck, this World War II drama unfolds entirely on a lifeboat adrift in the Atlantic, transforming a simple survival story into a complex exploration of human nature under extreme duress.

The film opens with a bang – literally. A luxury liner and a German U-boat have just sunk each other, leaving a motley crew of survivors to clamber aboard a solitary lifeboat. Among them is Constance “Connie” Porter (Tallulah Bankhead), a glamorous and cynical journalist who’s managed to save her mink coat and camera but little else.

Connie is joined by John Kovac (John Hodiak), a surly ship’s engineer; Gus Smith (William Bendix), a good-natured sailor with a gangrenous leg; Alice MacKenzie (Mary Anderson), a soft-spoken nurse; Charles D. Rittenhouse (Henry Hull), a wealthy industrialist; and Joe Spencer (Canada Lee), the ship’s steward and the sole African American survivor. The group’s uneasy alliance is further complicated when they rescue a German sailor, Willy (Walter Slezak), from the water.

Initially, the survivors are divided on whether to let him aboard, but practicality wins out – Willy is the only one who can navigate. As allegiances form and break, the characters’ positioning within the boat changes, with Willy often at the center as both a necessary evil and a focal point of suspicion. Close-ups capture every flicker of emotion on the actors’ faces, while wider shots emphasize the ocean’s vastness and the survivors’ vulnerability.

14. Marnie (1964)

Often overlooked in favor of the director’s more famous works, “Marnie” is a complex and challenging psychological thriller diving into the murky waters of trauma, sexuality, and obsession. The titular Marnie Edgar (Tippi Hedren) is a troubled young woman with a penchant for theft and a crippling fear of the color red. A master of disguise and deception, she moves from job to job, embezzling funds before vanishing without a trace. Her carefully constructed world begins to unravel when she catches the eye of Mark Rutland (Sean Connery), a wealthy widower who sees through her latest scheme but finds himself intrigued rather than outraged.

Mark, driven by a mix of attraction and a misguided desire to “cure” Marnie, blackmails her into marriage. What follows is a disturbing power struggle as Mark attempts to uncover the root of Marnie’s psychological issues while simultaneously trying to consummate their marriage – a goal hampered by Marnie’s severe aversion to physical touch. Hitchcock’s visual style shifts between lush Technicolor splendor and moments of stark, expressionistic horror.

The infamous “red wash” effect, where Marnie’s terror manifests as a crimson tint flooding the screen, is particularly striking as a bold subjective technique that plunges the viewer directly into Marnie’s fractured psyche. Hitchcock’s use of rear projection, while dated by today’s standards, adds to the film’s dreamlike quality, emphasizing Marnie’s disconnection from reality. A standout sequence involves Marnie riding her beloved horse, Forio, the rear projection creating a surreal, almost mythic atmosphere that underscores the character’s fleeting sense of freedom.

13. The Lady Vanishes (1938)

Showcasing Hitchcock at his most playful, “The Lady Vanishes,” opens in the fictional Central European country of Bandrika, where a motley crew of English travelers find themselves stranded at a quaint mountain inn due to an avalanche. Among them is Iris Henderson (Margaret Lockwood), a frivolous young socialite heading home to England to get married.

On the eve of their departure, Iris has a chance encounter with Miss Froy (Dame May Whitty), a kindly older lady and former governess. The next day, as their train winds its way through the Bandrikan countryside, Iris awakens from a nap to find Miss Froy has vanished without a trace. More bizarrely, all her fellow passengers deny ever having seen the old woman. Is Iris losing her mind, or is there something more sinister afoot?

Hitchcock uses the confined space of the train to create a sense of claustrophobia and paranoia, with each compartment potentially hiding friends or foes. His camera glides smoothly from compartment to compartment, each revealing a microcosm of society with its own miniature drama unfolding. On the surface, the film is a straightforward mystery thriller. Dig deeper, however, and you’ll find a sly commentary on British society on the eve of World War II. The film’s finale, a tense shootout, and chase sequence is a tour de force of suspense filmmaking. Hitchcock ratchets up the tension with each passing moment, culminating in a nail-biting race across the border to safety.

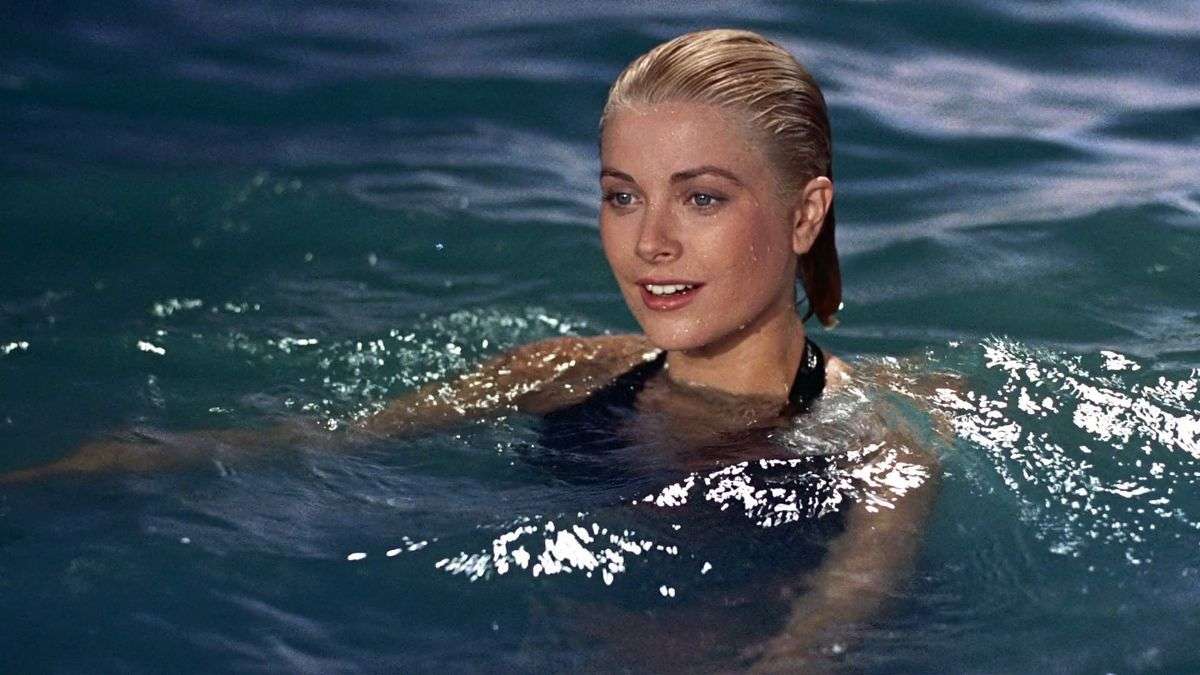

12. To Catch a Thief (1955)

Adapted from David Dodge’s eponymous 1952 novel, “To Catch a Thief” stars Cary Grant as John Robie, a reformed burglar known as “The Cat,” who finds himself forced to catch a copycat thief to clear his own name. The film sets off with a series of daring jewel heists along the Côte d’Azur, all bearing the hallmarks of Robie’s past exploits. Despite leaving his life of crime behind to become a respectable vineyard owner, Robie quickly becomes the prime suspect. Determined to prove his innocence, he sets out to catch the real culprit, enlisting the help of his old friends from the French Resistance and an insurance man named Hughson (John Williams).

Enter Frances Stevens (Grace Kelly), a cool blonde American heiress vacationing with her mother (Jessie Royce Landis). Intrigued by Robie’s mysterious air, Frances pursues him relentlessly, even after learning of his criminal past. Their cat-and-mouse game of seduction plays out against the backdrop of the Riviera’s most exclusive hotels and beaches, culminating in one of cinema’s most memorable fireworks displays – a sequence laden with sexual innuendo that somehow slipped past the censors of the day.

The film is a visual feast, with Robert Burks’ Oscar-winning cinematography capturing the sun-soaked beauty of the French Riviera in glorious VistaVision widescreen. The film’s climax at a costume ball is a masterpiece of misdirection and reveal, with Hitchcock using the colorful chaos of the event to keep both Robie and the audience guessing until the very end. The unmasking of the real thief is both surprising and satisfying, tying up the mystery while reinforcing the film’s themes of appearance versus reality.

11. Shadow of a Doubt (1943)

A masterful psychological thriller that peels back the veneer of small-town Americana to reveal the darkness lurking beneath, “Shadow of Doubt” has often been cited by Hitchcock himself to be his favorite among his works. It opens in a big city, where a man is fleeing unseen pursuers. This is Charles Oakley (Joseph Cotten), a charming but mysterious figure who decides to seek refuge with his unsuspecting sister Emma (Patricia Collinge) and her family in the idyllic town of Santa Rosa, California. His arrival is met with joy, especially by his adoring niece and namesake, Charlotte “Charlie” Newton (Teresa Wright), who sees her uncle as an exciting break from her humdrum small-town existence.

However, Young Charlie’s initial elation soon gives way to creeping suspicion as she begins to notice discrepancies in her uncle’s behavior. A series of coincidences – a torn newspaper article, a peculiar ring inscription, Uncle Charlie’s aversion to having his photograph taken – gradually coalesce into a horrifying realization: her beloved uncle may be the “Merry Widow Murderer,” a serial killer who preys on wealthy widows.

Hitchcock makes brilliant use of the small-town setting, contrasting the sunny, tree-lined streets of Santa Rosa with the growing darkness at the heart of the Newton household. The family dinner scenes, in particular, are marvels of understated tension, with Uncle Charlie’s misanthropic descriptions of widows as “fat wheezing animals” taking on a sinister double meaning. Young Charlie’s journey from naivete to grim understanding mirrors the loss of innocence on a broader scale, perhaps reflecting America’s own awakening to the horrors of World War II.

Also Related to Alfred Hitchcock’s Movies: 20 Underrated Films of 2014 Worth Watching Again

10. The Birds (1963)

Based loosely on a story by Daphne du Maurier, “The Birds” is one avian apocalypse that unleashes a nightmare scenario where nature itself turns against humanity, leaving audiences squirming in their seats and casting wary glances at the sky long after the credits roll. Socialite Melanie Daniels (Tippi Hedren) meets lawyer Mitch Brenner (Rod Taylor) in a bird shop in San Francisco. Their flirtatious encounter leads Melanie to follow Mitch to his hometown of Bodega Bay, bearing a gift of lovebirds. What begins as a romantic pursuit quickly descends into chaos as the coastal town becomes the epicenter of inexplicable and increasingly violent bird attacks.

Hitchcock builds the tension masterfully, starting with isolated incidents – a seagull pecking Melanie’s forehead, a flock of birds gathering ominously on a jungle gym – before unleashing full-scale avian warfare. The attacks escalate in both frequency and ferocity, culminating in scenes of pure terror: schoolchildren chased by crows, townsfolk trapped in a diner as birds smash through windows, and Melanie trapped in an attic as pecking beaks puncture the door.

Hitchcock and his team, including special effects artist Ub Iwerks, created the bird attacks through a combination of trained live birds, mechanical props, and groundbreaking composite shot images. The result is a series of sequences that remain shocking and convincing even by today’s standards. Instead of a traditional musical score, Hitchcock uses a sophisticated sound design featuring electronically manipulated bird calls created by Oskar Sala and Remi Gassmann. This unsettling soundscape and long stretches of eerie silence create a sense of unease that permeates the entire film.

9. Dial M for Murder (1954)

Adapted from Frederick Knott’s successful Broadway production, “Dial M for Murder” masterfully transforms a single-set stage play into a cinematic tour de force of suspense and psychological manipulation. The story revolves around Tony Wendice (Ray Milland), a former tennis pro who has married Margot (Grace Kelly) for her money. Upon discovering her affair with American crime fiction writer Mark Halliday (Robert Cummings), Tony concocts an elaborate scheme to have her murdered. He blackmails an old college acquaintance Charles Swann (Anthony Dawson) into carrying out the deed, planning every detail with meticulous precision. However, the seemingly perfect murder goes awry when Margot manages to kill her attacker in self-defense.

Tony, thinking on his feet, cleverly manipulates the evidence to frame Margot for premeditated murder. What follows is a battle of wits between Tony and the dogged Inspector Hubbard (John Williams), with Mark desperately trying to prove Margot’s innocence. Confined primarily to the Wendices’ apartment, Hitchcock uses every inch of the space to heighten tension. The camera glides smoothly through the rooms, revealing crucial details and emphasizing the characters’ physical and psychological entrapment.

Hitchcock’s trademark dark humor is evident throughout, particularly in the character of Inspector Hubbard. His methodical dismantling of Tony’s scheme provides moments of levity while ratcheting up the tension. The film’s climax, a battle of wits between Tony and Hubbard, is a masterpiece of suspense. As Hubbard methodically unravels the truth, the audience is kept guessing until the very end, with each new revelation shifting the balance of power.

8. Rebecca (1940)

“Rebecca” is a haunting psychological thriller that marked Hitchcock’s triumphant debut in Hollywood, a Gothic romance based on Daphne du Maurier’s 1938 novel of the same name. The unnamed protagonist (Joan Fontaine), a shy and naive young woman working as a lady’s companion, meets the dashing and wealthy Maxim de Winter (Laurence Olivier) in Monte Carlo. Their whirlwind romance culminates in marriage, and the new Mrs. de Winter finds herself whisked away to Manderley, her husband’s sprawling ancestral home. However, the young bride’s fairy tale quickly sours as she finds herself living in the shadow of Rebecca, Maxim’s deceased first wife. The new Mrs. de Winter is constantly reminded of her predecessor’s beauty, charm, and sophistication – qualities she feels she lacks.

This sense of inadequacy is exacerbated by the hostile presence of Mrs. Danvers (Judith Anderson), Manderley’s sinister housekeeper who remains fanatically devoted to Rebecca’s memory. As the protagonist struggles to find her place in Manderley, she becomes increasingly obsessed with Rebecca, whose unseen presence seems to permeate every corner of the estate. The truth about Rebecca’s death gradually unravels, revealing dark secrets that threaten to destroy the de Winters’ marriage and Maxim’s very life.

Hitchcock uses light and shadow to great effect, turning Manderley into a character in its own right. The grand staircase, Rebecca’s preserved bedroom, and the windswept beaches near the estate all become loaded with psychological significance. The protagonist’s journey from insecure girl to confident woman forms the emotional core of the film, while the mystery surrounding Rebecca’s death adds a layer of suspense that keeps viewers on edge.

7. Rope (1948)

Pushing the boundaries of cinematic technique while exploring the dark depths of human nature, “Rope” is a taut psychological thriller that unfolds in real time, creating a claustrophobic atmosphere that mirrors the moral suffocation of its protagonists. The story begins with a shocking act: two young men, Brandon Shaw (John Dall) and Phillip Morgan (Farley Granger), strangle their former classmate David Kentley (Dick Hogan) to death. Far from a crime of passion, this is a calculated experiment in the “art of murder,” inspired by their former prep school housemaster Rupert Cadell’s (James Stewart) philosophical musings on Nietzsche’s concept of the übermensch.

With cold-blooded audacity, Brandon and Phillip hide David’s body in a large chest in their living room. Then, in a twisted display of hubris, they host a dinner party, using the very chest containing their victim’s corpse as a macabre buffet table. Hitchcock’s formal innovation in “Rope” is its apparent single-take structure – composed of ten roughly ten-minute takes, cleverly edited to create the illusion of one continuous shot. This technique serves multiple purposes: it heightens the real-time tension, emphasizes the confined setting, and forces the audience into the role of the unwilling accomplice, unable to look away from the unfolding horror.

The camera prowls the apartment like an unseen guest, lingering on telling details – a tightening grip on a glass, a furtive glance, the ominous chest – creating a palpable sense of unease. “Rope” forces us to confront the dangers of taking ideas to their logical extremes, and the thin line between academic discourse and real-world consequences.

6. Strangers on a Train (1951)

Based on Patricia Highsmith’s 1950 novel, “Strangers on a Train” takes a simple premise and spins it into a dizzying web of moral ambiguity and psychological tension that ensnares both its characters and audience. The plot kicks off innocuously enough on a train, where tennis star Guy Haines (Farley Granger) meets the charismatic but unhinged Bruno Antony (Robert Walker). Their chance encounter quickly spirals into a nightmarish proposition: Bruno suggests they “swap murders,” each killing the person causing trouble in the other’s life. Guy laughs it off as a twisted joke, but Bruno is deadly serious. Guy wants to divorce his unfaithful wife Miriam (Laura Elliott) to marry Anne Morton (Ruth Roman), the daughter of an influential senator (Leo G. Carroll).

Bruno, meanwhile, chafes under the control of his wealthy father. In his warped logic, if Bruno kills Miriam and Guy kills Bruno’s father, they’ll both have airtight alibis. Guy’s horrified dismissal of the idea doesn’t deter Bruno, who sees their “agreement” as binding. Visually the film is a feast of light and shadow, with Hitchcock and cinematographer Robert Burks employing stark contrasts to highlight the moral dualities at play.

The film’s pivotal sequence – Bruno’s stalking and murder of Miriam at an amusement park – is a tour de force of cinematic technique. Hitchcock’s camera becomes a predator, tracking Miriam through crowds and onto a secluded island. The murder itself is portrayed with chilling restraint, reflected in the lenses of Miriam’s fallen glasses – a moment of terrible beauty that haunts the rest of the film.

5. North by Northwest (1959)

“North by Northwest” is Hitchcock’s cinematic rollercoaster ride following the tribulations of Roger O. Thornhill (Cary Grant), an advertising executive whose life is turned upside down when he’s mistaken for a government agent named George Kaplan. The film’s opening sequence sets the tone: a jazzy Saul Bass title sequence gives way to the hustle and bustle of Madison Avenue, where Thornhill swaggers through his day, more concerned with securing a taxi than the geopolitical intrigue about to ensnare him. In a case of wrong place, wrong time, Thornhill is kidnapped by two thugs who believe him to be Kaplan. Whisked away to the Long Island estate of Lester Townsend (Philip Ober), Thornhill finds himself face-to-face with the suave but sinister Phillip Vandamm (James Mason).

Thornhill, framed for murder and branded a fugitive, must navigate a world where nothing is as it seems. His journey takes him from the corridors of the United Nations (where a shocking assassination occurs) to the confined spaces of a train bound for Chicago. Here, he meets the enigmatic Eve Kendall (Eva Marie Saint), a cool blonde who’s more than she appears to be.

The film culminates in a showdown at Mount Rushmore, a vertigo-inducing chase across the presidents’ faces that serves as both a thrilling set piece and a wry comment on American iconography. Thornhill, the shallow ad man, literally clings to the facades of American leaders as he fights for his life and country. Ernest Lehman’s screenplay crackles with witty dialogue and inventive plot twists while Bernard Herrmann’s score, by turns playful and ominous, perfectly underscores the action.

4. Notorious (1946)

A sumptuous noir-tinged espionage thriller that sees Alfred Hitchcock operating at the peak of his powers, “Notorious” is a twisted romance following Alicia Huberman (Ingrid Bergman), the daughter of a convicted Nazi spy, as she’s recruited by U.S. agent T.R. Devlin (Cary Grant) for a dangerous mission in Rio de Janeiro. It opens with Alicia drowning her shame in alcohol and fast living. Devlin, cool and inscrutable, offers her a chance at redemption – and perhaps romance. Their burgeoning relationship is cut short when Alicia learns of her assignment: to seduce and marry Alexander Sebastian (Claude Rains), a Nazi collaborator with ties to a mysterious uranium-smuggling operation.

What follows is a masterclass in sustained tension, as Alicia infiltrates Sebastian’s world while Devlin watches from the sidelines, his professional mask barely concealing his jealousy and concern. The famous key scene, where Alicia secretly procures the key to Sebastian’s wine cellar, is a marvel of economical storytelling.

The camera slowly pushes in on Alicia’s hand, the key nestled in her palm becoming the focal point of the entire frame – and the film’s suspense. Alicia’s journey from “notorious” woman to heroic spy mirrors America’s own post-war rehabilitation. The film’s climax, a slow-motion escape down a grand staircase, is fraught with almost unbearable tension. Hitchcock stretches time to the breaking point, each step feeling like an eternity as Sebastian’s fellow Nazis close in.

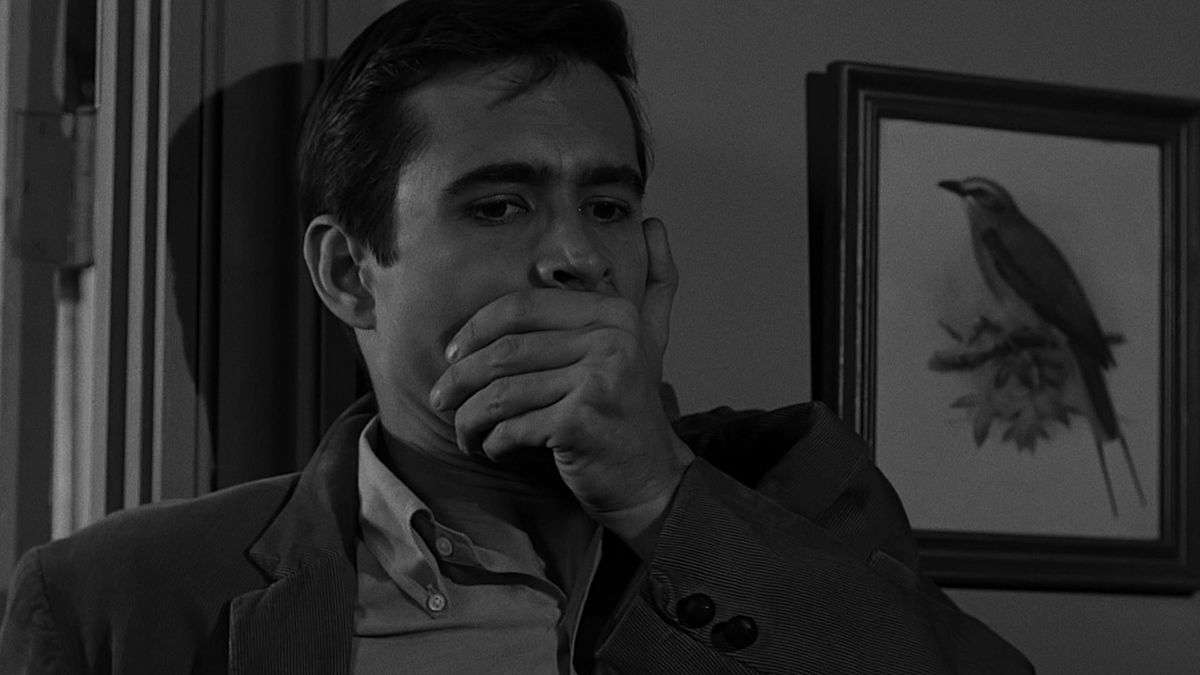

3. Psycho (1960)

Hitchcock’s macabre masterpiece “Psycho” is a psychological horror thriller that begins rather deceptively: following Marion Crane (Janet Leigh), a Phoenix secretary who impulsively steals $40,000 from her employer and flees towards California, her conscience and a torrential rainstorm nipping at her heels. The exhausted Marion pulls into the remote Bates Motel, where she encounters the seemingly shy and affable proprietor, Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins). Their quietly charged conversation over sandwiches and milk in Norman’s parlor, surrounded by his unsettling taxidermy, is a masterclass in building tension through dialogue and atmosphere. But it is what follows that cemented “Psycho” in the annals of cinema history.

The infamous shower scene, where Marion is brutally murdered, remains one of the most analyzed sequences in film. Hitchcock’s rapid-fire editing, Bernard Herrmann’s screeching strings, and the implied violence of the scene (the knife never actually makes contact) combine to create a moment of pure, visceral terror. It’s a sequence that feels far more graphic than it actually is, a testament to Hitchcock’s ability to manipulate audience perception. From this point, “Psycho” pulls the rug out from under the viewer repeatedly and each step deeper into the mystery brings us closer to the twisted heart of the Bates Motel and its occupants.

Shot in black and white, the film has a stark, almost documentary-like quality that enhances its horror. The director’s use of point-of-view shots and unsettling angles keeps the audience off-balance throughout. Norman’s outward politeness conceals monstrous impulses, mirroring the film’s setting: a motel just off the newly constructed highway system, a symbol of progress harboring ancient evils.

2. Vertigo (1958)

A dizzying descent into obsession, desire, and the malleability of identity, “Vertigo” follows John “Scottie” Ferguson (James Stewart), a San Francisco detective forced into early retirement due to a crippling fear of heights. Scottie’s old college acquaintance, Gavin Elster (Tom Helmore), hires him to follow his wife Madeleine (Kim Novak), who Elster claims is possessed by the spirit of her great-grandmother Carlotta Valdes.

As Scottie trails Madeleine through sun-dappled San Francisco, he becomes entranced by her ethereal beauty and apparent vulnerability. Their paths inevitably cross, and a romance blossoms, tinged with the knowledge of Madeleine’s supposed doom. But in a gut-wrenching sequence atop a Spanish mission bell tower, Scottie’s acrophobia prevents him from saving Madeleine as she plunges to her death.

Consumed by guilt and grief, Scottie descends into a spiral of depression until months later, when he encounters Judy Barton (also Kim Novak), a shop girl who bears an uncanny resemblance to Madeleine. Hitchcock’s famous “dolly zoom” effect, created for the film to simulate Scottie’s vertigo, has now become iconic.

The dreamlike quality of Scottie’s pursuit of Madeleine is enhanced by Robert Burks’ lush cinematography and Bernard Herrmann’s haunting, swirling score. The use of color is particularly striking, with vibrant greens and reds creating a sense of unreality and obsession. “Vertigo” explores the nature of identity and the tension between appearance and reality. Scottie’s attempt to recreate Madeleine through Judy speaks to the impossibility of recapturing the past and the destructive nature of idealized love.

1. Rear Window (1954)

Alfred Hitchcock’s masterful exploration of voyeurism, morality, and the nature of relationships – all viewed through the lens of a housebound photographer’s camera. “Rear Window” is a claustrophobic thriller that confines us to the apartment of L.B. “Jeff” Jefferies (James Stewart), a globe-trotting photojournalist temporarily wheelchair-bound due to a broken leg. Restless and bored, Jeff begins to observe the lives of his neighbors through the rear window of his Greenwich Village apartment. What starts as idle curiosity soon transforms into obsession as Jeff becomes convinced that Lars Thorwald (Raymond Burr), a traveling salesman across the courtyard, has murdered his invalid wife.

Jeff’s girlfriend Lisa Fremont (Grace Kelly) initially dismisses his suspicions as the product of an overactive imagination. However, she’s gradually drawn into his amateur sleuthing, along with Jeff’s skeptical but caring nurse Stella (Thelma Ritter). As the trio delves deeper into the mystery, the line between justified investigation and unethical intrusion becomes increasingly blurred. The entire film is shot from Jeff’s apartment, with the courtyard and its inhabitants becoming a microcosm of human drama.

Each window frames a different story – a struggling composer, a lonely woman dubbed “Miss Lonelyhearts,” newlyweds in the throes of passion – creating a tapestry of life that Jeff (and by extension, the audience) hungrily devours. “Rear Window” questions the ethics of such observation while simultaneously reveling in its pleasures. It’s a meta-commentary on filmmaking itself, with Jeff as the director, framing and interpreting the scenes before him.