Although there’s been much fuss made about gender discrimination in the film industry, with pledges made by many film festivals to ensure gender parity, it should be blindly obvious that asymmetries in workplace diversity do not automatically mean active discrimination. The Film Industry’s Gender Parity has brought an unending debate into question. This unsubstantiated discrimination has been identified and a reverse kind of discrimination has been enacted to combat it. Genius!

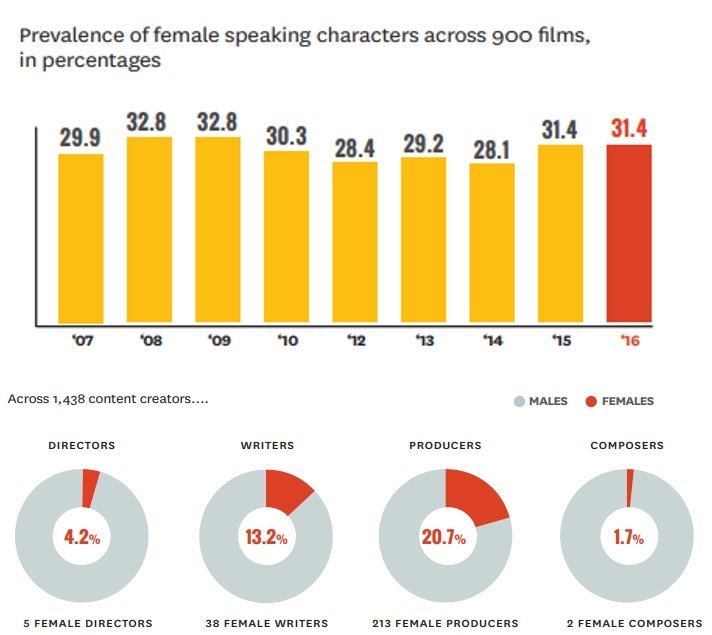

The statistics are certainly out there to prove there’s less women in the film industry than men, across nearly all occupations. What is perhaps the leading study on this matter, ‘Inequality in 900 Popular Films’, analysed the top 100 grossing films in the US from 2007-2016 (excluding 2011) and found that women are lacking not just on screen, but also behind the screen.

But what is it exactly causing this imbalance? The study doesn’t delve any deeper in explaining why, neither identifying any unfair barriers put in place for women or any female-related lifestyle factors that may affect their careers in this regard – but nonetheless, this study makes many suggestions that involve quota systems and gender parity.

Related to The Film Industry’s Gender Parity – The 20 Best Women-Directed Films Of 2017

The most famous of which is the equity clause, now known as inclusion rider, which if adopted by a certain actor or filmmaker, stipulates that the film production they’re working on must have an imposed equitably diverse crew (as to what signifies ‘diverse’, as in race, gender, sexual orientation, political alignment, socioeconomic status, or porn fetish, hasn’t quite been clarified).

Among suggesting that film workers, companies, and shareholders enact diverse checklists like these, the study also suggests ‘Just Add Five’ which claims that if just five women were added to every film (in the top 100 grossers of the year), there would be gender parity for on-screen talent by, well, this year. Sounds like filmmakers weren’t too keen on this experiment over the years, especially when films set in certain scenarios (wars, historical moments, infrastructure workplaces, S&M clubs) would have a hard time shoehorning this stipulation in.

Another checklist for the film industry is the Time’s Up movement’s 4% Challenge (taking its name from the fact that women only make up 4% of US directors), where those in the industry comply to work with a female director in the next eighteen months (preferably black, gay, disabled, conservative). This has been adopted by Hollywood big wigs Universal, Dreamworks, MGM, and Focus, along with many actors including Ben Affleck, Matt Damon, Paul Feig, Michael B. Jordan, and Brie Larson.

Another study analysing the gender stats is ‘Cut Out of the Picture’, which details the lesser paid roles, showing that females dominate in Costume and Casting departments, but make up a vast minority in most other roles, the worst of which are Transportation (7.8%) and Electrical (5.1%). Gee, that’s surprising, given that women are also in the vast minority for these roles even outside of the film industry.

With all these statistical outcomes, we indeed see a gender imbalance in most roles in the film industry, showing just how much men are the majority (whereas the world’s population, and movie-goer population, is equally as much women as it is men). But there need to be far more research and studying into the reason for this imbalance – if female-only barriers are identified, they must be eradicated as much as possible.

Yet instead, we have forced equity and parity that demands that all film roles be equal. The wider world of workplaces does not operate this way, and it never has. There’s currently not much of a movement to get more men into early age teaching roles, and nor should there be – this goes to show the imbalance there is in correcting the gender imbalance in the workforces.

Although having more women in the film industry would be great, this way of making it so is an egregious and lazy method. But with enforced equity and parity becoming more and more the norm, the future of filmmaking can have men feel that their work is being considered less than a women’s, and that women feel their success has been based more on quota hiring systems rather than their talent.

For more whinging and moaning from the author that could be mischaracterised as sexism, watch his video below.