There appears to be something wrong with comedy films. They are not held in as high esteem as drama films, and for good reason. Maybe it’s a problem that has always persisted, but it is still very much evident in modern comedies, and if this is to be resolved, comedy films either need: a drastic reforming to better utilise the unique benefits comedies can attain through the medium of cinema that drama films can’t, or; to be funnier.

Read the other entries:

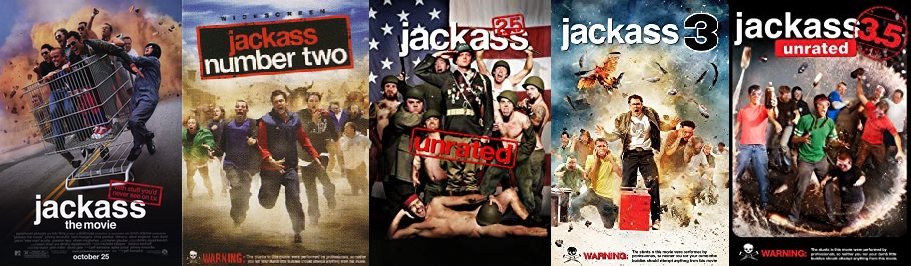

Introduction I – Too Much realism, not enough surrealism, Introduction II – Golden Globes for Best Comedy, Solution I: Everything Is Terrible!- Playing Upon Expectations, Solution II: Jackass Movies- The Hilarity of the Human Body, Solution III: Paul McCarthy and Dadaism, Solution IV: So bad, it’s good, Conclusion: Theories of Comedy

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

The gross-out sub-genre appears to be a lost art in today’s comedy films, replaced with the more middlebrow, low-key, and less brash dramedies discussed in this series’ earlier articles. It’s a shame that this more extreme form of comedy isn’t as present as it used to be and can’t seem to co-exist in this age of talkative, character-focused comedies that rarely aspire for any sort of visceral humour.

Two of the key features in gross-out comedies, the slapstick stunt-work and the messy discharge of bodily fluids, resonate in similar ways to how dangerous stunts are performed in action films and how fluids are spilled in body horror films. They are both represented, with no movie-magic trickery, in the Jackass films.

There’s something peculiarly voyeuristic about witnessing and empathising with these acts of inevitably painful danger and gross-out mayhem. This kind of on-camera behaviour appears to be so juvenile and brainless, but there’s also a quality to it that pushes the boundaries of what the human body can take (or ingest) – this same ethos is explored in a number of reality shows like Fear Factor, Wipe Out, and the plethora of similarly themed masochistic Japanese game shows.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

This boundary-pushing desire, whether to observe it or be active in it, is undeniably a facet that has been part of humanity since before he even became homo sapiens. Watching these films is a safe way of conjuring this very primal desire whilst remaining entirely safe and clean, all the while still a spectator to the pain and humiliation of these stunts and gags.

As opposed to their contemporaries (Dirty Sanchez, The Dudesons) and the aforementioned game shows, Jackass takes this to a higher level, not only through invoking a lot of cartoonish creativity and craftsmanship in their stunts, but also putting all the pain and shame solely on those involved in the stunts.

The editing of each of the three movies (and the two mini-movies, 2.5 and 3.5) consistently keeps a perfect ratio of how much to show of the stunts and how much to show of the reactions. Most of the Jackass crew is present when even one person is performing a stunt, and their reaction shots of them mockingly pointing and laughing and maybe even simply throwing up are an essential aspect of what makes a stunt, no matter how disgusting, so endearing.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

Comedian Louis CK notes that it’s the presentation of the Jackass on-lookers pointing and laughing and mocking each other’s pain and humiliation that makes the movies not only so funny, but identifiable. It’s awful to empathise with the Jackass who’s involved in a stunt, but the Jackass on-lookers are easy to empathise with as they epitomise the audience who delight in sadistically gawking at these masochists.

And it’s this kind of camaraderie that seems to be missing from Johnny Knoxville’s new film, Action Point (2018), where the group of man-children doubled over in hysterics is replaced with cackling children, which doesn’t look anywhere near as authentic. Besides, when making the transition from TV show to movies, Jackass didn’t bother with shoehorning an overarching storyline to accompany all the stunts, which most certainly would’ve diluted both the stunts and the narrative.

The Jackass films perfected this brand of on-camera nonsense and endangerment. Little on pretentiousness (they don’t even care for upper case letters), some of the stunts can last as little as ten seconds on screen, with each of the five films keeping themselves air-tight as to not waste any time – they simply set up the gag, show its horrific execution, and the reactions and aftermath. It’s a simple formula that they made last across eight years in the first decade of the millennium.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

The main takeaway from the Jackass films is their proliferation of both the slapstick extremities of their inventive stunt-work and the disgusting discharging of bodily fluids, all of which is heightened because of its unmovie-like authenticity. This visceral, impressive, shocking, and often cinematic facet of comedy ought to make a return so that the genre can reclaim using the human body to invoke such a powerfully impactful effect on the audience. The Jackass films aren’t for everyone (they’re likely not for most people), but they should still be identified as a potential inspiration for a return of gross-out comedies.

To see either Buster Keaton, Wile E. Coyote, or Johnny Knoxville let go off all their bodily inhibitions as they flail through the air towards certain destruction (or put themselves in the most disgusting vomit-inducing situations) all goes to show just how humorous the human body can be – Jackass distils that notion down to its finest essence.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

![Gonjiam: Haunted Asylum [2018] – A Welcome Entry in Found-Footage Horror](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/gonjiam-screenshot-1-768x413.jpg)

![Onward [2020] Review: Another Forward Step for Pixar](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Onward-cover-768x432.jpg)