Midway through the second part, I had a screaming epiphany. Until that point, Tryst with Destiny (SonyLiv) seemed to be, yet another film driven by social themes, without anything extraordinary to see, visually at least. Nothing struck me as out of order. Everything seemed normal, and at times, admittedly so, even funny. But it is that very ignorance, my inability to perceive, that Nair so earnestly exploits. His confrontational style is a gifted mix of subtle and above-board.

The moment I saw what director Prashant Nair was trying to do by saying so little and creating this macabre narrative theme, a sense of reluctant calm inundated me. Sans visual grandeur or Shyamalan-like twists, ‘Tryst’ is compelling in a more modest, sombre way. Nair presses to establish a dialogue with the viewer, hoping, but strangely assured, that somewhere along the way, after the screen is turned off, there will be sincere deliberation.

Related to Tryst with Destiny (SonyLiv): Ajeeb Dastaans (2021) – Geeli Puchhi Review

It is in its most vulnerable moments that Prashant Nair’s anthology drama that the truth of our society prevails over the mindless sugar coating we see in media and pop culture. Tryst with Destiny (SonyLiv) is as much about India’s identity and unique social fabric as it is a searing look inwards into the lives of people confronting their destinies on a fateful day.

The title, taken from the late Jawaharlal Nehru’s famed speech in the Parliament, metaphorically alludes to both a national and individual crisis that marginalized sects of people go through in India. Nair’s deft storytelling, though, allows the film’s thematic core to also accommodate themes with a universal character that make the viewing even broader in scope. The four parts – ‘Fair’ and Fine’, ‘The River’, ‘One BHK’, and ‘Beast Within’ – form part of the same timeline and are interconnected events through the news and mass media.

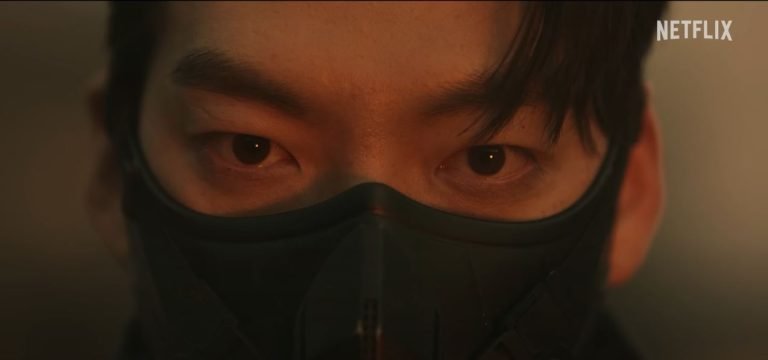

Jaideep Ahlawat, Kani Kusruti, Ashish Vidyarthi, and Vineet Kumar Singh form part of a formidable acting ensemble. Their job to emote is made harder due to Nair’s filmmaking choices but nonetheless an exciting challenge. The stereotype that birthed their characters’ identities has gradually turned into malicious labelling that ostracizes them from normal conversations. Calling someone a kaala jamun might have seemed innocuous merry-making shenanigans in school but a foot outside in the real world makes a torrential difference.

Vidhyarthi’s Mudiraj, after the incident, confides in her wife with a heartbreakingly resigned look that simply says, “what else must I do?” The power and wealth he accumulated in his life aren’t enough to dissuade the common populace from looking down at him plainly due to the colour of his skin.

The meteoric rise from a chaiwala to a business tycoon somehow takes a backseat to how society perceives him based on how he looks. Inside the four walls of our house, our sanctuary-like bedrooms, we do not hesitate much before calling derogatorily the likes of Gautam and Ahalya by a word I have the decency not to write here. It has all been so normalized in mundane conversations that any mention of it being hurtful or insulting to a person seems to alien, and in Gen Z terms, ‘woke’.

Also Read: Aakashvaani (2021) SonyLiv Review

India has reached a breaking point. Its critical mass now rests tenderly at the intersection of cultural and generational paradigm shifts. Nair’s use of national symbols like mango, tiger, and the foreboding match of hockey, is a hopeful representation of a new conscience, a sort of rebirth of India. His idea of an India is not fragmented by timid conditionalities like caste, religion, the colour of one’s skin, and gender, all grounds ironically, constitutionally prohibited to be discriminated upon. Instead, it is defined by love, acceptance, and tolerance. These three are, for me, the three key takeaways from ‘Tryst with Destiny’. Nair’s polemic indictment of institutions that comprise the foundation of our social structure and preservation is complete with his observant inclusion of nature and ecology in his narrative setup.

The film is bound to make you uneasy and urge you to skip certain scenes (the non-curfew nights in the second part), but that would be a tragedy. Sit through them and there is a significant chance that the motley of emotions you feel will have a sense of shame and guilt.

![H6 [2021]: ‘Cannes’ Review – A Deeply Heartfelt Documentary about Hope and Healthcare](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/h6-cannes-768x415.jpeg)

![Memoria [2021]: ‘HIFF’ Review – Tilda Swinton-led Mystery Isn’t Bothered With Answers](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Memoria-1-highonfilms-768x512.jpg)

![Ananta (The Eternal) [2022]: ‘KIFF’ Review – Turgid, Lifeless & bereft of a fundamental clarity](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Ananta-The-Eternal-KIFF-Movie-Review-1-768x503.jpg)