Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (1954) is an undisputed masterpiece of cinema. But there’s a greatness within it that was hidden from the worldview at the time of its release. Keep an eye out for the scene where the villagers come to town to recruit wandering, masterless samurai for their cause. The great Tatsuya Nakadai, then 21 years of age, graces the screen for a few seconds as an extra (an impoverished ronin). It was the actor’s first appearance on the big screen, although technically, he made his screen debut (in a very small role) in Masaki Kobayashi’s prison drama, The Thick-Walled Room, completed in 1953. The film depicted how, during the American Occupation of Japan, the low-ranking Japanese soldiers were convicted of war crimes, whereas their officers and high-ranking policymakers remained scot-free.

Though the US Occupation of Japan ended in 1952, the content was deemed controversial, and Kobayashi chose to shelve the film rather than make the cuts in order to release it (the film was released in 1956 without any cuts). Subsequently, Masaki Kobayashi continued to make incendiary sociopolitical cinema about post-war Japan and became the era’s most important humanist and anti-authoritarian filmmaker. There’s a story that Kobayashi found Nakadai while the latter was working as a shop clerk.

Born in 1932, Tatsuya Nakdai was trained as a stage actor, mainly influenced by the Shingeki tradition of realistic drama. By the early 1960s, Nakadai, with his piercing eyes and photogenic face, gradually attained hard-won celebrity status. The embodiment of the idealistic Kaji in Kobayashi’s epic drama, The Human Condition trilogy, became Nakadai’s first breakthrough role. Throughout the ’60s, he worked with great Japanese filmmakers, from Mikio Naruse, Akira Kurosawa to Keisuke Kinoshita, Kon Ichikawa, and Kihachi Okamoto.

Recommended Read: 50 Best Japanese Movies of the 21st Century

Tatsuya Nakadai might be less recognizable than his fellow charismatic star, Toshiro Mifune. But this electrifying performer with a rich baritone voice surprises us with his extraordinary versatility. Moreover, the ever-passionate Nakadai kept working on stage, movies, and television, offering supercharged performances in the 21st century, too. From an 11th-century obstinate artist to a 21st-century grieving widower, Nakadai has lived many lives across centuries through his incredible on-screen personas.

With wide-eyed amazement and profound joy, I have invested myself in exploring Nakadai’s vast filmography. In fact, to see Nakadai and all other legendary actors at their best is to be aware of a new capacity in cinematic art. The following list is an attempt to address the popular as well as lesser-known Tatsuya Nakadai performances. It’s simply a first step towards making a more comprehensive list of the venerated thespian’s works. The ranking below is strictly based on my evaluation of Nakadai’s performance (not a ranking of the movies he starred in).

Honorable Mentions:

Kwaidan (1964)

Masaki Kobayashi’s extravagantly designed Kwaidan is a horror anthology film. However, the chilling yet strangely relaxing folktales presented here differs from the Western approach to the horror genre. Kwaidan’s dreamlike landscapes and inexplicable events elegantly transport us to a malevolent and vengeful realm where spirits coexist alongside humans. The four tales in this portmanteau are based on Anglo-Greek author and teacher Patrick Lafcadio Hearn’s collection of Japanese ghost stories and legends (published in 1904). Tatsuya Nakadai plays the central role in the second story, The Woman in the Snow. The then 32-year-old actor was cast as the 18-year-old woodcutter Minokichi.

During a blizzard, Minokichi and an old man take refuge in a hut deep in the forest. A blue-skinned spirit woman kills the old man but takes pity on the young man. However, she warns him about mentioning this incident to anyone. Sometime later, Minokichi comes across a beautiful young woman. They fall in love and lead a happy married life until Minokichi recounts the tale of the snow woman to his wife. Though it’s a small role, it’s memorable for Nakadai’s visceral expression of fear through his eyes. Far removed from the political assertions of The Human Condition Trilogy or Harakiri, Kobayashi in Kwaidan guides us into a storybook-like world that’s further bolstered by elegant performances.

Odd Obsession (1959)

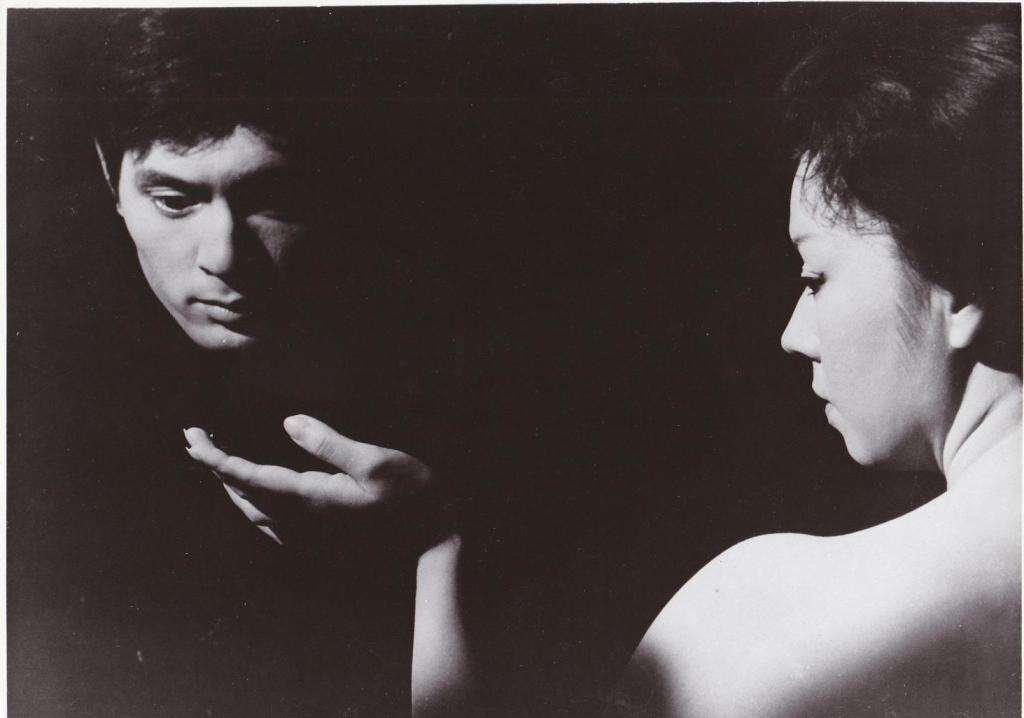

Based on Junichiro Tanizaki’s 1956 novel The Key, Kon Ichikawa’s adaptation revolves around an aging art critic and antique collector, Kenmochi (Ganjiro Nakamura). Kenmochi’s younger and beautiful wife, Ikuko (Machiko Kyo), and the desire to restore his flagging virility push the man to take shots from the ambitious, young doctor and family friend, Kimura (Tatsuya Nakadai). Dr. Kimura warns Kenmochi about his rising blood pressure due to the shots.

Soon, Kenmochi, apart from relying on injections, initiates an odd game to stimulate his sex drive by bringing together his wife and Kimura. What makes it more weird is that Dr. Kimura is dating Kenmochi-Ikuko’s daughter, Toshiko. Of course, it leads to events with unintended consequences. Odd Obsession opens with a fourth-wall-breaking scene, as Nakadai’s Kimura looks at the camera and provides a brief lecture on the human body’s frailty. Machiko Kyo and Nakamura in the lead characters offer top-notch performances, and Nakadai’s creepy presence as the cryptic Dr. Kimura brings out the darkly comic and discomfiting layers of the narrative. Nakdai relishes the chance to play a refined yet duplicitous young man.

Related to Tatsuya Nakadai Movies – 20 Great Psychosexual Movies that are Worth your Time

Lover Under the Crucifix (1962)

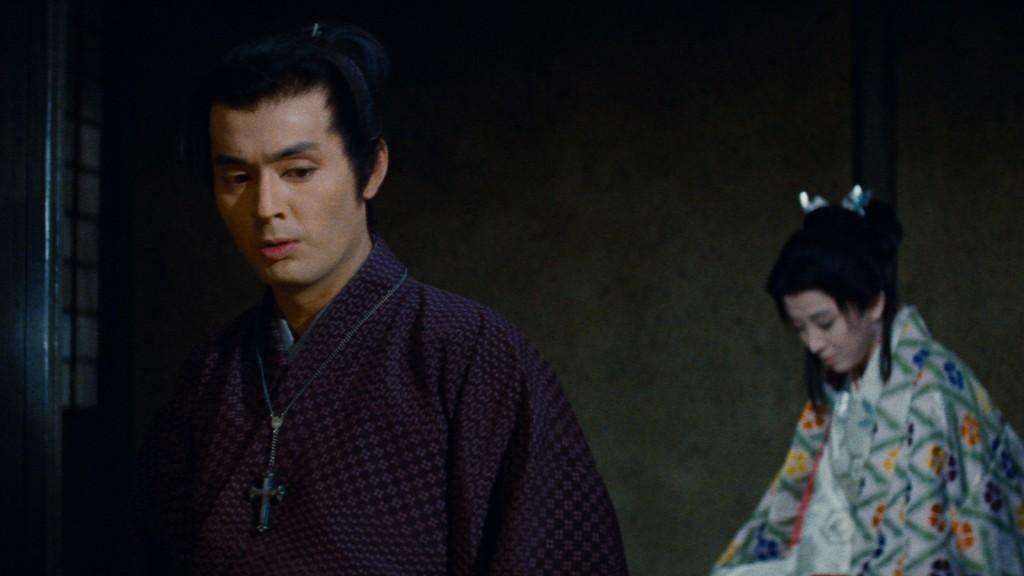

Love Under the Crucifix is the sixth and final directorial effort of prolific female actor Kinuyo Tanaka, best known for her collaborations with Kenji Mizoguchi. This was Tanaka’s only film to be set in feudal Japan. Love Under the Crucifix is set in 1580s Japan, a period of social upheavals and Christian persecution. The turbulent late 16th-century politics serves as a backdrop for the narrative’s central love affair between Ogin (Ineko Arima) – stepdaughter of the renowned tea master Rikyu – and a young Christian lord, Ukon (Tatsuya Nakadai).

The film mostly unfolds from Ogin’s perspective as she strives to pursue her love for Ukon despite the rigid social conventions of the era. It’s a magnificently shot melodrama, and one particularly striking aspect of the film is the restrained performances. Nakadai appears in a few scenes and effortlessly brings to life a repressed young man. The actor subtly portrays Ukon’s religiosity, which pushes him to be a stony-hearted individual. Ineko Arima and Ganjiro Nakamura’s (as Rikyu) roles are relatively more substantial than Nakadai’s. Yet the actor brings the relevant emotional authenticity to Ukon despite the limited screen time.

30. The Scandalous Adventures of Buraikan (1970)

Buraikan marks Tatsuya Nakadai’s first and only collaboration with the prominent Japanese New Wave filmmaker Masahiro Shinoda. Set in the 1840s “Tempo Reforms” period – an era of restrictive censorship laws – the narrative follows three pivotal characters living in and around the Yoshiawara red light district of Edo (Tokyo). The titular ‘Buraikan’ (ruffian or outlaw) is played by Tetsuro Tamba. Nakadai offers a delectably over-the-top performance as Naojiro, a ronin, and a wannabe actor. Naojiro falls in love with the sex worker, Michitose (Shima Iwashita), and tries to get away from his domineering mother (Suisen Ichikawa).

Shinoda’s film focuses on the ordinary people who were impacted by the stringent reforms. But the tenuous thread linking the stories is underdeveloped, and the narrative takes a purely farcical tone that doesn’t always work. Thankfully, Shinoda’s striking visual compositions, color design, and Nakadai’s comical performance make it entertaining enough. The most intriguing aspect of Buraikan is Naojiro’s twisted relationship with his mother. Of course, the film will not work for everyone, but if you want to watch Nakadai in an unrestrained and unconventional avatar, then this is for you.

29. Hachiko Monogatari (1987)

The legend of the Japanese Akita dog, Hachiko, is well-known, at least among dog lovers. Lasse Hallstrom transplanted the Japanese tale to America in his maudlin tear-jerker, Hachi (2009). But long before Hallstrom, Seijiro Koyama & Kaneto Shindo turned the true story into a tragic and astounding tale of loyalty. Hachiko Monogatari is the Japanese counterpart to the big-screen American dog pictures like Lassie and Benji. Set in the 1920s Tokyo, the narrative revolves around Professor Shujiro Ueno (Tatsuya Nakadai) of Tokyo University. A purebred Akita, born during a blizzard, is sent to the professor as a gift by his friend. Ueno instantly falls in love with the puppy and names him Hachiko.

As the professor takes the train to the university, Hachiko follows him to the station. Later in the evening, when the professor’s train is about to arrive, Hachi shows up at the station. Hachi appeared at the station regularly, but one day, the professor didn’t come home in the evening. Nevertheless, till his last breath, the unwaveringly loyal Hachi waited for his master outside the station. Nakadai offers a restrained performance as Professor Ueno. There’s not a false note of sentimentality in his acting, which deeply saddens us once he exits the story. Of course, the cute and heart-melting Hachiko demands most of our attention.

Related to Tatsuya Nakdai Movies: The 20 Best Dog Movies of All Time

28. Willful Murder (1981)

Kei Kumai was an underrated Japanese filmmaker whose dramatic narratives withhold incendiary sociopolitical critique about the militaristic and post-war Japanese society. In Willful Murder, Kumai chronicles the infamous Shimoyama Incident of 1949. Mr. Shimoyama, the President of the Japanese Railways, goes missing for a short while and is later found dead, run by a train. It was a turbulent era in the America-occupied train, particularly in the railway sector, as Shimoyama was forced to control the unions and initiate mass layoffs.

Though Shimoyama’s death is officially ruled as suicide, a determined reporter’s initial findings make it clear that there’s a larger conspiracy behind the powerful man’s death. Tatsuya Nakadai plays Yashiro, an investigative journalist who stubbornly pursues the case for nearly two decades despite a murder attempt and after receiving many death threats. Nakadai mostly offers a grounded performance, although he adapts an old-school, melodramatic style of acting in some dramatic moments. The majestic screen presence of Nakadai effortlessly immerses us into the narrative, which touches upon various political events of post-war Japan.

27. Yojimbo (1961)

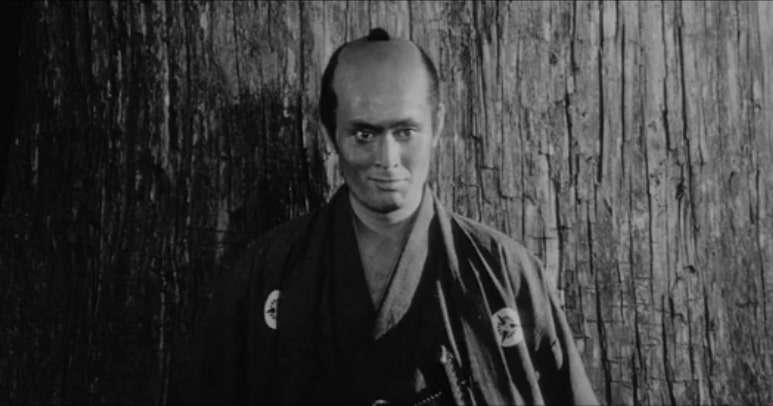

“He died as recklessly as he lived,” says Toshiro Mifune’s crafty nameless ronin about Tatsuya Nakadai’s gun-toting gangster. Set in the later half of the nineteenth century, during the waning years of Tokugawa Shogunate, Yojimbo revolves around Mifune’s ronin, who arrives at a small town where two rival gangs fight for control. He plays one gang off against the other and, in the ensuing conflict, tries to make some money. His motives are initially obscure, just like the name he gives himself – Sanjuro Kuwabatake – after looking at a mulberry field (which means ‘30-year-old Mulberry Field’). But he never loses sight of his humanity and helps those in need.

One of Sanjuro’s rivals is Unosuke (Nakadai). He likes instigating violence as much as Mifune’s character but utterly lacks a moral compass. Sporting a wicked smile and a revolver, Nakadai’s Unosuke comes across as a symbol of encroaching modern civilization. Though it’s a tiny role, Nakadai effortlessly holds his own against the towering screen presence of Mifune. He also gets a flamboyant death scene. Yojimbo marks Nakadai’s first proper collaboration with Akira Kurosawa (though he made his screen debut as an extra in ‘Seven Samurai’).

26. Inn of Evil (1971)

Inn of Evil (Inochi Bonifuro) was the last of the four Masaki Kobayashi films to be set in feudal-era Japan. It’s a dark, tragic ensemble drama set inside an enclave of hardened criminals and smugglers. It’s called Easy Tavern, conveniently located on a small island in the middle of the Edo River. A single walkway connects the place to the mainland. The gang’s operation has so far gone smoothly, but new police officials vow to bring down the gang. All the members of the gang are social outcasts, and the most sullen and cynical among the bunch is Sadashichi ‘The Indifferent’ (Tatsuya Nakadai).

Inn of Evil isn’t a protagonist-oriented tale. All the uncaring and selfish characters eventually come together to commit a selfless act. However, the most exciting and well-rounded character in the film is Sadashichi. He kills a police officer in cold blood but anxiously looks after a lost baby bird, hoping it gets reunited with its mother. It’s a character of many contradictions, and Nakadai’s portrayal makes us sympathize with Sada. Inn of Evil, however, feels underwhelming compared to Kobayashi’s Harakiri, Kwaidan, and Samurai Rebellion.

25. Conflagration (1958)

Kon Ichikawa’s Conflagration (Enjo) is loosely based on Yukio Mishima’s renowned novel The Temple of the Golden Pavilion. The film chronicles the psychological breakdown of Goichi Mizoguchi (Raizo Ichikawa), a young man with a stutter. During the war, naive and introverted Goichi is sent to the famous Shukaku Golden Temple in Kyoto as an apprentice to the head monk. Like his dead father, Goichi cherishes the shrine. However, the post-war tourist boom corrupts the temple’s head priest and other monks.

Goichi’s slow embrace of nihilism and pessimism begins with his friendship with the club-footed student, Tokari (Tatsuya Nakadai). Goichi is deeply disturbed by Tokari’s reckless and manipulative behavior. Nevertheless, Goichi looks up to him like a brother. Nakadai’s mesmerizing screen presence (particularly his apathetic gaze) makes this supporting character very memorable. Tokari slyly pushes Goichi to believe that their shared disabilities make them a kindred spirit. Nakadai’s character effortlessly passes his own insecurities and misplaced anger to Goichi, which culminates with a devastating act.

24. Japan’s Tragedy (2012)

Shot with a pared-down minimalist aesthetic in monochrome, Masahiro Kobayashi’s one-location movie Japan’s Tragedy revolves around grief-stricken Murai Fujio (Tatsuya Nakadai), diagnosed with lung cancer. In 2010, as the recession was at its peak, 31,650 Japanese took their lives in the year. A year later, the devastating Tohoku earthquake and tsunami claimed the lives of more than 20,000. Japan’s Tragedy deals with both these themes through the stark challenges faced by Fujio and his family.

Fujio is discharged from the hospital with the news that he will only last a few months. Not wanting to delay his death, Fujio shuts his room’s doors and windows, sits in front of the portrait of his dead wife, and decides to starve himself to death like a Buddhist monk. His divorced and unemployed son, Yoshio (Kitamura Kazuki), implores him to give up his extreme methods. Moreover, Yoshio is burdened with grief, as his wife and daughter are missing after the 2011 earthquake. Released on the 50th anniversary of Harakiri, Nakadai shows that he is still the perfect actor who can heartrendingly portray grief and fortitude on-screen. Masahiro’s indelible close-ups of Nakadai’s face befittingly convey the fragility of human life.

Related to Tatsuya Nakdai Movies – 15 Essential Japanese Silent Films

23. Princess Goh/Go-hime (1992)

Hiroshi Teshigahara’s final film, Princess Goh, is a sequel of sorts to Rikyu (1989), a refined drama on the titular tea ceremony master. Set between the late 16th century and early 17th century, Rikyu & Princess Goh explores the turbulent times that led to the emergence of the Tokugawa political system through the perspective of the Noble class. Both these films from Teshighara are devoid of the avant-garde aesthetics of his early films (Woman in the Dunes, The Face of Another, etc). It’s a rather stately and slow-paced jidaigeki drama comprising magnificent performances from Rentaro Mikuni, Tsutomu Yamazaki, Rie Miyazawa (as Princess Goh), and Tatsuya Nakadai.

Nakadai plays Rikyu’s protege, Furuta Oribe, who is made the new tea master for daimyo Toyotomi Hideyoshi. In the later years, Oribe is employed by Hideyoshi’s rival, Tokugawa Ieyasu. The strictly codified tea ceremonies played a significant role in politics and diplomacy in Feudal-era Japan. Nakadai’s Oribe remains the epitome of restrained elegance. The friendship between Oribe and the vibrant Tomboyish Princess Goh is one of the storyline’s poignant aspects. Nakadai’s performance is particularly heartwarming in the reunion scene between Oribe and Goh and later when he bids farewell to his loyal gardener, Usu. Though it’s a supporting character, watching Nakadai play a regal character is always a treat.

22. Hitokiri (1969)

Hideo Gosha’s ultraviolet saga Hitokiri, like many renowned samurai flicks, is set during the downfall of Tokugawa Shogunate, i.e., the 1860s. As Japan gradually left feudalism behind for a modernized form of government, the winds of change brought myriad conflicts. One such famous tale set in this era is that of Okada Izo, a skillful yet capricious samurai and a feared assassin – hitokiri. In Gosha’s rendition of Izo’s story, veteran actor Shintaro Katsu (of Zatoichi fame) plays Izo, and Tatsuya Nakadai dons the role of Takechi Hanpeita, a cold and cunning samurai leader of the Tosa Loyalist Party. Though officially Takechi sought reforms and to overthrow the Tokugawa, he covertly used his elite team of samurai assassins to achieve his sinister agenda.

Katsu brilliantly rises to the challenge of playing the uncouth and naive Izo. He offers an unforgettable physical performance, showcasing the feral, foolish, and vulnerable sides of Izo. Nakadai’s Takechi perfectly contrasts Katsu’s character. He maintains a calm facade while playing the ruthless political game. Nakadai’s deep voice and brooding glances firmly establish Takechi’s increasing deviousness. One more important member of the cast is author Yukio Mishima as Izo’s rival, Shinbei Tanaka.

21. Samurai Rebellion (1967)

Masaki Kobayashi’s Samurai Rebellion was a slightly lesser film than the director’s masterpiece Harakiri (1962). And Tatsuya Nakadai plays a small role than his expansive screen presence in Harakiri. However, both films offer an extraordinary study of individuals’ rebellion against the implacable power structures of feudal-era Japan. Toshiro Mifune co-produced and played the central role of Sasahara Isaburo, a highly respected member of Lord Matsudaira’s cavalry escort. Set in the 1720s, i.e., the middle years of Tokugawa Shogunate (1603-1868), the narrative revolves around the Sasahara family’s complex conflict with the domain’s Lord.

Nakadai plays Isaburo’s friend Tatewaki Asano. He is also the warrior who guards the border gates of the clan’s domain. Earlier in the narrative, Tatewaki is hinted as the only worthy rival who can face Isaburo in a duel. As anticipated, a duel does ensue towards the end. However, it’s as brief and sharp as Kobayashi’s sword fights in Harakiri. Nakadai’s Tatewaki is a keen observer and the only person who perfectly comprehends Isaburo’s intentions. The character’s stoic exterior doesn’t betray his deepest feelings, except for the poignant moment before the final duel.

20. Sanjuro (1962)

I deeply feel that cinematic perfection is Toshiro Mifune and Tatsuya Nakadai sharing screen space together, however fleeting the moment is. The master filmmaker Akira Kurosawa offers quite a few memorable moments of such ilk in Sanjuro, a sequel of sorts to Yojimbo. Based on Shugoro Yamamoto’s story, Sanjuro follows the intelligent, skilled, and drifting ronin (Mifune) as he saves nine bumbling young samurai and their Chamberlain from the complex political games. Tatsuya Nakadai plays Hanbei Muroto, the ideal samurai retainer for the corrupt Superintendent Kikui.

With his trademark shoulder twitching and beard scratching, Mifune offers a phenomenal performance as the no-holds-barred samurai. Nakadai’s Muroto is bound by the bushido and follows orders without worrying about right and wrong. Nakadai’s posture and manner of speaking are more restrained here than the antagonist character he played in Yojimbo. Muroto is as much a skillful warrior as Mifune’s Sanjuro, whereas Unosuke (in Yojimbo) is an impulsive hoodlum. What makes Sanjuro more memorable, with regards to Nakadai, is the final duel. Mifune and Nakadai stare at each other for close to 30 seconds before drawing swords –- perhaps the most incredible sword draw in the history of cinema.

Related to Tatsuya Nakdai Movies: List of 100 Best Movies by Japanese Filmmaker Akira Kurosawa

19. Immortal Love (1961)

Keisuke Kinoshita’s beautifully shot melodrama Immortal Love (Eien no hito) sees the pairing of Tatsuya Nakadai and the incredible Hideko Takamine. Divided into five chapters, Immortal Love unfolds over three decades (between 1932 and 1961) and chronicles the loveless marriage of Sadako (Takamine). The film opens with the village landlord’s son, Heibei (Nakadai), returning from the Manchurian War with a limp. The cowardly and pathetic Heibei sets his sights on Sadako despite learning about her love for the tenant farmer’s son, Takashi. Hebei sexually assaults Sadako and cunningly forces her into a marriage.

The relationship between Heibei and Sadako only turns more caustic over the years. Kinoshita anchors this story of ruined lives through the bleak characterization of incorrigible Heibei. Nakadai’s Heibei remains a symbol of the Japanese ruling class decay. In the initial acts, Nakadai’s furtive glances and harsh words reveal the character’s despicable nature. However, Heibei comes across as a tragic, pitiable, and solitary figure in his old age. Nakadai matches up with Takamine’s beguiling performance, especially during their final conversation set inside the house (an uninterrupted long shot). Both the actors brilliantly underplay in this moving scene.

18. I Am a Cat (1975)

Kon Ichikawa’s I Am a Cat is an adaptation of Natsume Soseki’s popular serialized novel written between 1904 and 1906. The novel offers a satirical take on the Meiji period, making fun of the uneasy balance between Western influence and traditional notions through the world-weary perspective of a school teacher’s cat. Ichikawa transplants the sardonic humor of the feline to Tatsuya Nakadai’s middle-class English teacher, Kushami. Though cats adorn the movie’s frames, except for the final scenes, the vignette-based narrative mostly unfolds from Kushami’s perspective, who is navigating his way through the enervating mundanity of domestic life.

I Am a Cat is the kind of great novel that’s ‘unfilmable.’ And although Ichikawa’s adaptation doesn’t quite come together as a movie, Nakadai’s witty flair is a joy to experience. Sporting a bushy mustache and sideburns, Nakadai’s Kushami hilariously tries to reconcile with the modern standards and his traditional upbringing. From comical rant to expressing melancholy, yearning, and resentment, Nakadai’s antics are thoroughly enjoyable. The film has quite a few laugh-out-loud moments, particularly the scenes between Nakadai and Juzo Itami (director of Tampopo), who plays Kushami’s best friend, Meitei.

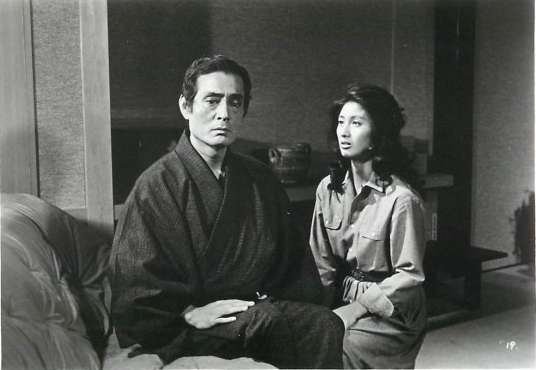

17. When a Woman Ascends the Stairs (1960)

Tatsuya Nakadai credits Hideko Takamine (with whom he has acted in several films) and Mikio Naruse for helping him to with restrained performances early in his career, where he had to interiorize his characters’ conflicts. Nakadai has worked with Naruse in five films; the best among them is the 1960 film When a Woman Ascends the Stairs. Based on Ryuzo Kikushima’s original screenplay, the film chronicles the conflicts in the life of Keiko (Takamine), an independent and aging hostess operating in the glitzy Ginza entertainment district. Naruse is a master at portraying the tales of unheard or unseen women caught in the maelstrom of male-dominated post-war Japanese society. And When a Woman Ascends the Stairs was crafted by the legend with nuance and great care.

The prolific Nakadai plays Kenichi Komatsu, the bar manager and friend of Takamine’s Keiko. Kenichi admires her and supports Keiko in opening her own bar. Moreover, Kenichi’s stoic exterior barely conceals the intense feelings of love he harbors for her. The emotional yet restrained confrontation scene (towards the end) between Nakadai’s Kenichi and Keiko is fascinatingly performed, as Kenichi’s affable nature and air of professionalism are replaced with vulnerability and acrimony. His rigid perception of Keiko is unfair, and it is to Nakadai’s credit he doesn’t reduce the fallible Kenichi into a repulsive man.

16. High and Low (1963)

Akira Kurosawa’s tense and meticulous police procedural, High and Low, is based on Ed McBain’s 1959 novel, King’s Ransom. It revolves around the shoe company executive, Kingo Gondo (Toshiro Mifune), who becomes the target of an intelligent and cold-blooded kidnapper. High and Low stands tall as one of the greatest thrillers in cinema due to Akira Kurosawa’s masterful staging and blocking techniques. Tatsuya Nakadai plays the supporting role of the diligent chief detective Tokura, who maintains a sense of urgency throughout the narrative. Tokura and his men are also silent observers like us, as Mifune’s Gondo wrestles with his conscience to do the right thing.

In the film’s later half, as the focus shifts from Gondo’s inner turmoil to the daunting investigation, Nakadai’s low-key performance remains a crucial element that holds together the narrative. Though it’s a character that remains in the periphery amidst Kurosawa’s expressive staging, it is the detective’s undying commitment that eventually solves the case. Right from the moment Tokura makes his appearance, often dressed in a suit and tie, Nakadai gracefully carries professional confidence, even though the scenario gets increasingly tempestuous.

15. Black River (1957)

Black River (Kuroi kawa) was Masaki Kobayashi’s yet another scathing critique of post-war Japanese society. It marks the first major collaboration between Kobayashi and Nakadai, though the actor has previously played a bit role in Thick-Walled Room (1956). Black River portrays multiple intersecting stories set in a lower-class neighborhood situated close to a US military base. The film opens with the burgeoning love affair between a student, Nishida, and a young waitress, Shizuko. But a dreaded yakuza guy named Killer Joe (Nakadai) sets his eye on Shizuko.

Tatsuya Nakadai has played negative roles in his long career. He was the stylish villain in Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo. However, Joe in Black River is clearly one of the most despicable characters he has played. The guy is a veritable sleazebag who makes Shizuko ‘his girl’ by raping her. His inventory of evil deeds only gets worse from there. At one point, Joe casually says to Shizuko, “When I’m in love, I’m cruel to my girl. Bad upbringing, I guess…”

Nakadai’s Joe totally dominates the narrative. Whenever Joe is on screen, we get the feeling that this character is beyond redemption and incapable of any humane gestures. The bleakest Kobayashi film offered Nakadai his first recognizable role, and their collaboration continued till Kobayashi’s last film, Family Without a Dinner Table (1985).

14. Onimasa (1982)

Based on Tomiko Miyao’s novel, Hideo Gosha’s Onimasa revolves around a reckless aging patriarch of a yakuza clan. While Tatsuya Nakadai plays the titular character, the story largely unfolds from the perspective of his adopted daughter, Matsue (an extraordinary Masako Natsume). Set in the Taisho era (1912-1926), when Japan was transforming into a modern nation heavily influenced by Western style and taste, we witness the contrast in the outlooks of the yakuza father and his educated daughter. Though Matsue is depicted as the central character, Nakadai’s towering on-screen persona makes it a bit of an unbalanced character study of the two equally fascinating characters.

As the mercurial Onimasa, Nakadai plays the character with an abundance of swagger while also unearthing the yakuza’s darker and vulnerable sides. Nakadai’s Onimasa considers himself an old-fashioned honorable samurai who stands up for his principles. But he is also a deeply authoritarian individual who gradually loses the hold over his domain. He is a relic of the past, and it is Nakadai’s operatic performance that keeps us occupied till the bitter conclusion.

Hideo Gosha was best known for his classics in the Chanbara and yakuza genres. With Onimasa, he eschews the genre tropes to provide an absorbing and compelling drama. After the 1971 movie The Wolves, this is definitely the last great collaborative work between Nakadai and Gosha.

13. Kill! (1968)

Writer/director Kihachi Okamoto is best known in the West for his samurai classics, such as Samurai Assassin (1965) and The Sword of Doom (1966). While Okamoto’s jidaigeki flicks can be relentlessly bleak, Kill elegantly balances between goofy comedy and a grounded drama. In a wonderfully ironic fashion, Okamoto looks at the absurdity of the samurai code and the violence it breeds. The film opens at a windy, dilapidated village on March 1833, as a wannabe samurai, Hanjiro Tabata (Etsushi Takahashi), and the yakuza, Genta (Tatsuya Nakadai) stumble into its streets, ravaged by hunger. They witness a group of seven dedicated samurai banding together to take down a corrupt chamberlain.

But when the seven are double-crossed, Genta plays his intelligent game against the system. Nakadai’s Genta is a Sanjuro-like character sans the inimitable macho swagger of Toshiro Mifune. In fact, Kill’s original story was from the same author – Shugoro Yamamoto. Nakadai plays the world-weary Genta while effortlessly blending his profoundly humane personality with the matter-of-fact bluntness of a warrior. There’s only a brief moment of rollicking swordfight, where Nakadai’s Genta showcases his fighting prowess. Most of the time, he employs his clever hijinks to win over the enemy. The contrast between Nakadai’s stoicism and Takahashi’s buffoonery remains one of the compelling aspects of this spaghetti Western-style samurai comedy.

Related to Tatsuya Nakadai Movies – Ten Best Western Showdowns

12. Goyokin (1969)

Tatsuya Nakadai has collaborated with Hideo Gosha on eleven films, and the action/drama Goyokin is one of the best in their respective careers. Like Kihachi Okamoto’s Kill! (1968), Gosha’s film blends Chanbara movie tropes with elements from the Western genre. At the same time, Goyokin is a somber drama, whereas Kill! withholds a sense of parody. Nakadai plays Magobei Wakizaka, a guilt-ridden, self-exiled ronin. Set in the 1830s, during a period of great unrest, the title refers to the gold and silver mined from Sado island that’s shipped to Tokugawa shogunate’s capital city, Edo (Tokyo).

The local Sabai clan, burdened by debt, uses the inhabitants of a fishing village to sink the cargo ship and steal the Shogun’s gold. Subsequently, the Sabai clan’s chief retainer, Tatewaki (Tetsuro Tanba), orders his men to massacre the villagers to keep it a secret. Magobei, a clan official and brother-in-law of Tatewaki, is shocked by the actions but doesn’t speak of what occurred. Three years later, when Tatewaki decides to execute the same plan in a different village, Mogobei returns to his homeland to stop the killings. Nakadai once again excels in playing a tormented warrior, rejecting the rigid codes to embrace his humanity. The snowcapped landscape bestows a singular quality to the action set pieces, and Nakadai’s intense gaze adds extra fire to the swordplay.

11. Haru’s Journey (2010)

Masahiro Kobayashi is known for his austere style of filmmaking. His works had a strong following in festival circuits, although largely neglected at home. Unlike Japan’s Tragedy or his other independent films, the 2010 road movie Haru’s Journey is his most easily accessible work and can be a fine entry point to his oeuvre. The movie also marks the first of three collaborations between Masahiro Kobayashi and Tatsuya Nakadai. When we see first Nakadai’s septuagenarian Tadao Nakai, angrily storming out of his home, followed by his anxiety-ridden granddaughter, Haru (an excellent Eri Tokunaga), we are instantly gripped by this zealous performer. The narrative has a simple premise of the two central characters traveling in search of a home for Tadao by visiting his siblings since Haru needs to move to a city and find a new job.

On this quest, the two rediscover their bonds, confront the dark past, reconcile, and walk away with touching realizations. Though Nakadai initially comes across as a meanspirited old fisherman, through subtle glances and gestures, the amazing thespian meticulously evokes Tadao’s ineradicable love for his granddaughter alongside the man’s regrets, fears, and grief. As we get lost in the emotional spaces of Tadao and Haru, we are showered with simple yet beautiful moments that make us break into a smile as well as move us to tears.

10. Portrait of Hell (1969)

Shiro Toyoda’s Portrait of Hell is based on Ryunosuke Akutagawa’s 1918 short story Hell Screen. Set in the 11th-century Heian era, the narrative chronicles the face-off between an obstinate artist of Korean heritage, Yoshihide (Tatsuya Nakadai), and the vainglorious Lord Hosokawa (Kinnosuke Nakamura). Sporting the dreamlike and macabre atmosphere of a theatrical play, Toyoda’s intriguing mise en scene and Nakadai’s commanding performance elevate this languid morality play. Nakadai often excels at playing defiant characters speaking truth to power. But unlike the righteous heroes the actor has played in Kobayashi’s films, Yoshihide is a prideful and prejudiced man, often preoccupied with the game of one-upmanship.

The hedonistic Lord Hosokawa repeatedly censures Yoshihide for creating dark and ‘ugly’ canvases instead of painting a vision of paradise. The ever-brooding artist insists that he only paints what he sees. To belittle the artist, the Lord uses Yoshihide’s young daughter (Yoko Naito) as bait and challenges him to create a perfect mural of Hell. If looks can set things ablaze, then Nakadai could be a weapon of mass destruction. Such is his intensity in the moments he confronts the Lord and when he attempts to evoke the astoundingly disturbing visions of hellscape. His descent into despair engulfs us like hellfire.

Related to Tatsuya Nakadai Movies: 15 Great Films About Troubled Geniuses

9. The Wolves (1971)

Hideo Gosha, the master of Chanbara classics in the 1960s, gradually transitioned to the yakuza genre in the 1970s, starting with The Wolves. In the same decade, the yakuza genre reached its peak with Kinji Fukusaku’s quintessential “Yakuza Papers” series (1973-1974). Starring Gosha’s frequent collaborator, Tatsuya Nakadai, the narrative is set in the 1920s and follows the exploits of Seiji Iwahashi (Nakadai), who spends a few years in prison after getting involved in the murder of a rival syndicate’s boss. Iwahashi was pardoned after Emperor Hirohita’s ascension to the throne (in 1926). The world of yakuza has undergone several changes while Iwahashi was in prison.

He finds that his gang has formed an alliance with the new boss of the rival gang and is involved in some shady deals. Though The Wolves has a familiar or cliched plot, Gosha’s robust character development and meditative pace allow us to reflect on the themes and characters’ conflicts. Nakadai plays his signature ‘tortured hero’ with stunning effortlessness. A feeling of pensive sadness occupies us as we witness Nakadai’s Iwahashi traversing through a changed, treacherous world – a wellspring of sorrow and turmoil keeps exuding from his eyes. Another striking element of the film is the way Gosha shoots violence. He brilliantly retains the ugliness and shocking nature of the violent act.

8. The Age of Assassins (1967)

Tatsuya Nakadai has taken part in many fierce on-screen katana fights, but we haven’t seen him much as a suave, modern action hero, wearing a suit and cleverly dispatching his enemies with personalized weapons. So, it’s a surprise to see Nakadai doing a Bond-type role with abundant charm in Kihachi Okamoto’s The Age of Assassins. While Okamoto has made the devastatingly brutal Samurai Assassin (1965) and Sword of Doom (1966), he is also a master at making parodies and satires. The Age of Assassins is one such example of Okamoto’s amazing versatility.

Nakadai’s Shinji Kikyo is first introduced as a bumbling criminal psychology professor who seems to be a random target of a mad assassin. Not every actor can look outrageously funny while they are hamming it up. Nakadai plays the bespectacled weirdo character with an expressiveness that consistently tickles our funny bones. As the narrative progresses, Shinji transforms himself into a super-stylish agent to understand the ulterior motive of a Murder Inc. Moreover, we wonder whether Shinji has really implicated himself in the conspiracy by chance. Who thought Nakadai could do both Peter Sellers and James Bond in a single movie?! This most entertaining Nakadai performance is further strengthened by Okamoto’s energetic action set pieces and playful cuts.

7. The Face of Another (1966)

The ever-changing nature of identity is a prevalent theme in Hiroshi Teshigahara’s movies, especially in the movies he collaborated with novelist Kobe Abe. In The Face of Another, Teshigahara and Abe follow the inner conflicts of an everyday salaryman, Mr. Okuyama (Tatsuya Nakadai), whose face is burned off in an industrial accident. His psychiatrist suggests a radical experiment as Okuyama wears a prosthetic mask. Wearing the face of another, Okuyama initially feels a sense of liberty, but gradually, the new persona pushes him to tap into his warped personality. While Abe’s masterwork Woman in the Dunes was perfectly adapted into a movie, The Face of Another remains too oblique. The attempt to literalize its themes through thought-provoking diatribes doesn’t always work in the film narrative.

Yet, Teshigahara’s ability to maintain a disorienting mood and Nakadai’s subtle performance make this examination of an individual’s scarred visage and broken soul compelling enough. Nakadai’s Okuyama spits out vitriol (often directed at Mrs. Okuyama, played by Machiko Kyo) with an evenness that shocks us. Then there’s the unnerving laughs. While Nakadai has previously played characters that are casually brutal, he is a dreadfully nihilistic figure in this movie. Interestingly, Nakadai stupendously played another unlikeable character in the same year in Okamoto’s The Sword of Doom.

Related to Tatsuya Nakdai Movies: 10 Best Movies on Crisis-Ridden Facial Surgery

6. Family Without a Dinner Table (1985)

Masaki Kobayashi’s final film examines a family broken apart by its eldest son’s extremist activities. It is set in the aftermath of the 1972 Asama-Sanso Incident – a 10-day televised violent stand-off between the United Red Army (URA) and the law enforcement authorities at a mountain lodge. The incident brought out the cult-like atrocities of the United Red Army and led to the decline of left-wing movements in Japan. Kobayashi and Fumiko Enji’s script fictionalizes the impact of the incident on one URA member’s family. Tatsuya Nakadai plays the Kidoji family patriarch, Mr. Nabayuki, a well-to-do scientist with a wife and three children.

His rational approach to dealing with his grown-up son, Otohiko’s crimes, makes him look like a cold-hearted person. Nabayuki’s alleged cavalier attitude is considered inappropriate in a nation where parents are expected to apologize for their children’s crimes publicly. His individuality is scoffed off in a society of conformists. This anxiety to take responsibility for Otohiko gradually destroys his family. Nabayuki, like the classic Kobayashi-Nakadai protagonists (Kaji or Hanshiro Tsugumo), refuses to easily give in to social oppression. However, beneath Nabayuki’s stoic exterior lies profound emotions and desires.

Nakadai magnificently draws out the complexities of the anguished patriarch. While from the 1970s, Nakadai increasingly played roles that brought out a theatrical style of performance, Family without a Dinner (aka The Empty Table) emphasizes his nuanced acting abilities. Here, he chooses to restrain himself and to rely on silence. The writing is too mawkish and unsubtle in places, and the trimmed VHS-quality print doesn’t allow us to evaluate Kobayashi’s imagery. Yet the film remains gripping throughout due to Nakadai’s excellent portrayal of a resolute and isolated father.

5. Kagemusha (1980)

Though Tatsuya Nakadai has collaborated with Akira Kurosawa on three films before Kagemusha, in the 1980 jidaigeki epic, the actor played the first of his two leading roles in a Kurosawa movie. Set during the Sengoku Period (1467-1568), aka Warring States Period, the narrative follows a petty thief (Tatsuya Nakadai) who is recruited to be the body-double of a powerful warlord, Shingen (also Nakadai). But when Shingen is killed, the thief impersonates him full-time and needs to keep up the ruse to prevent the enemies from attacking.

Kagemusha opens with a mesmerizing candle-lit shot of a meeting between Lord Shingen, his brother Nobukado (Tsutomu Yamazaki), and the thief. All three men wear identical clothes, but the way Kurosawa has lit the scene brilliantly distinguishes the Lord and his shadow. And Nakadai plays both the characters with easily discernible posture and voice modulations. This scene sets the stage for one of the most fascinatingly dramatic performances of Nakadai. The unceremonious and impetuous nature of the thief is a classic Kurosawa character. As the narrative progresses, Nakadai’s thief, internally and externally, undergoes an extraordinary transformation to become a figure of nobility and keen intellect.

Shintaro Katsu was Kurosawa’s initial choice for the dual role. While it’s criticized that Nakadai’s casting has diminished the narrative’s comedic tone, I believe the actor’s commanding screen presence offers a more believable and humane portrait of two radically different individuals.

Related to Tatsuya Nakadai Movies: The 25 Greatest Cannes Film Festival Palme d’Or Winners of All Time, Ranked

4. Ran (1985)

Revered as Akira Kurosawa’s last greatest masterpiece, Ran might haunt our memories through the ghostly Noh-style make-up worn by Tatsuya Nakadai’s Hidetora Ichimonji, an aging 16th-century Sengoku era warlord. Nakadai’s expressive eyes have always been his greatest strength. From manifesting righteous fury to exuding bad-boy charisma and heartfelt melancholy, the chameleonic performer can do wonders with his eyes. In Ran, Nakadai’s abdicated monarch spirals into madness as his visage reflects the indescribable torments burning deep inside him. Like Throne of Blood (1957), Ran is a Noh theatre-style adaptation of Shakespeare’s masterwork – King Lear.

For Ran, Nakadai splendidly veers into the broad and theatrical style of acting that’s prevalent in Kurosawa’s feudal-era narratives. He initially wears some make-up to transform himself into the much older patriarch of the Ichimonji clan (Nakadai was 53 years old at the time). As Hidetora witnesses the betrayal and greed of his sons and confronts the ghosts of his past, he roams the wastelands in horror, cloaked in white, like a spirit or demon haunting the lands. The image of Nakadai’s Hidetora emerging from the burning castle with a vacant stare is perhaps one of the most extraordinary moments in cinematic history.

Overall, Kurosawa’s timeless commentary on human struggles through the sorrowful, agonizing final days of a ruthless warlord is perfectly complimented by Nakadai’s magisterial performance.

3. The Sword of Doom (1966)

“The world’s full of villains, but he beats them all,” says a character about Tatsuya Nakadai’s Ryunosuke, the anti-hero at the center of Kihachi Okamoto’s acclaimed samurai classic, The Sword of Doom. While Nakadai has played quite a few vile characters, nothing comes close to his unsettling screen presence in this film. Based on Kaizan Nakazato’s serialized novel, The Sword of Doom unfolds between 1860 and 1863, a turbulent period in Japan’s political landscape as the Tokugawa era (1603-1868) was coming to an end.

Ryunosuke Tsukue is a gifted swordsman with an unusual style. He is born into a well-to-do noble clan, but the black-hearted samurai’s penchant for killing and cruelty banishes him from his village. Subsequently, he becomes a sword for hire and remorselessly kills people until a breaking point when the ghosts of his past materialize and deeply haunt him. Director Okamoto’s eclectic mix of styles – arthouse aesthetics with intensely kinetic swordplay flicks – and pitch-black darkness that exudes out of Nakadai’s eyes makes this an unforgettable movie experience. Toshiro Mifune plays a small yet spellbinding role as Toranosuke Shimada, the head of the sword-fighting school, who is a perfect match in skill to Ryunosuke.

Though the two master performers don’t cross swords in the film, Okamoto sustains ample tension in the moments Nakadai and Mifune battle with dialogues. Mifune’s Shimada gets his own rousing snow-filled swordplay, at the end of which he delivers these blistering words, referencing Ryunosuke: “The sword is the soul. Evil mind, evil sword.” Tatsuya Nakadai has mentioned that, among the many roles he embodied, he found it hard to get into Ryunosuke’s mind. Nevertheless, this bone-chilling performance from the actor flawlessly realizes a person wholly consumed by violence.

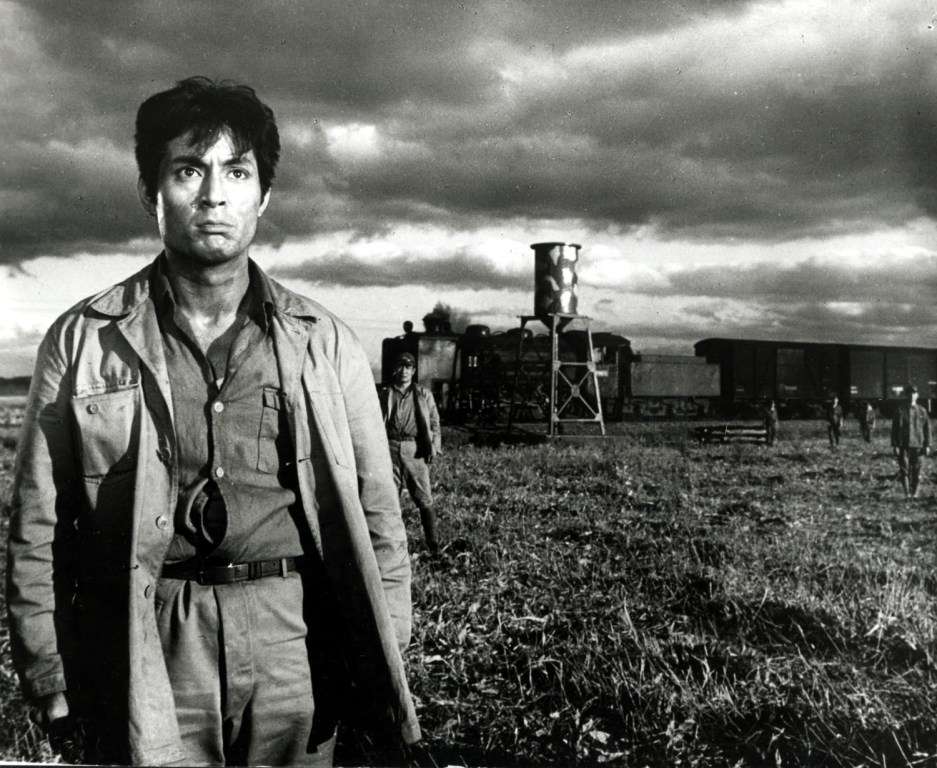

2. The Human Condition Trilogy (1959-1961)

Masaki Kobayashi’s magnum opus, The Human Trilogy, is based on the best-selling six-part novel by Junpei Gomikawa. With a nine-hour plus running time, this sweeping humanist drama chronicles the life of Kaji, a principled young man, during the grim WWII years. Kaji is assigned the supervisor role at an inhumane labor camp in Japanese-occupied Manchuria, controlled by authoritarian Japanese army commanders. Kaji’s humanist and pacifist outlook, with a touch of naivete, pushes him to combat the apathetic bureaucracy. But soon, Kaji himself is caught in the maelstrom of war, where his morals remain an impediment to survival.

Mr. Kobayashi, through his high-minded protagonist, somberly reflects the realities of wartime and post-war Japan. Kaji is a monumental character whose misfortunes showcase the profound impact of war on an individual. And it’s hard to imagine anyone apart from Tatsuya Nakadai to sharply evoke the myriad interior conflicts of Kaji. Kaji’s transformation from a thriving idealist to a disenchanted and haunted soldier is conveyed through a breathtaking range of emotions by Nakadai. Each of Kaji’s humiliations, small victories, ineradicable trauma, and moral lapse strongly register in our minds due to Nakadai’s stunning performance. It is hard to take our eyes off Nakadai’s Kaji in the final moments of the tale as the man staggers through a vast landscape, and his dejected visage carries years of emotional pain.

In the hands of a lesser director and actor, this anti-war epic’s melodramatic layers might have a wearying effect on the viewers. But Kobayashi’s expressive staging and Nakadai’s penetrative gaze make us ponder the madness of war.

1. Harakiri (1962)

While Tatsuya Nakdai has delivered several extraordinary performances in his long career, the unparalleled intensity with which he plays the impoverished and wronged ronin, Hanshiro Tsugumo, makes it the role of his lifetime. Masaki Kobayashi’s Harakiri is a damning critique of the authoritarian system, where power-hungry individuals hide behind the facade of principle and honor. Who can forget Kobayashi’s stunning symmetrical composition and stark lighting, which symbolizes the inhumanity of the feudal system? How can we not be gripped by the visual tension that flows through the brief, elegant sword-fight action sequences? Can you remain unmoved by the horrible fate of a ronin who tells a simple lie to save his starving family? And who wasn’t haunted by Toru Takemitsu’s magnificent score?

Despite such multiple strengths, Kobayashi’s core themes and visual motifs wouldn’t have the same power if not for Nakadai’s extraordinary screen presence. In each revisit, despite being aware of the reason behind the hollow-eyed Tsugumo’s arrival at the Iyi clan’s gates, I am repeatedly mesmerized by the wide range of Nakadai’s performance. From the stoic demeanor, the taunting laughs to the long dramatic stares, emotional breakdown, and ferocious sword fights, Nakadai registers each aspect of the tale in an undeniably vibrant manner.

Harakiri ends with unnerving images as the tyrannical clan methodically obliterates the remaining traces of an individual’s rebellion from the pages of history. But nothing can erase the greater glory of this Tatsuya Nakadai performance from the history of cinema.

Related to Tatsuya Nakadai Movies: The 20 Best Revenge Movies of All Time