Filmography of Carlos Reygadas: According to Paul Schrader, transcendental style is a constant pursuit of the unspeakable and invisible. Schrader explores the universal characteristic of these films, rising above the manifestations of an insensible world into a sensuous existence. They do this by bringing an irrational passion to the cinema, which offers the viewer a way to perceive objects in another medium. In transcendental-style films, the ultimate catharsis does not come from the action. Statis [1] is only affected by what has already happened.

By delaying editing cuts, immobilizing the camera, ignoring musical accompaniment, rejecting the technique of shooting the action from all sides, and emphasizing monotony, the transcendental style creates a certain anxiety that the viewer must overcome. The director promotes the audience’s tendency to overcome anxiety and discomfort with a “decisive action”; this is an unexpected image or action, which then transforms into stasis, accepting a parallel reality – the transcendent, writes Shrader [2].

Transcendent style film directors aspire to create not Polished but Cleaned shots. The transcendent style aspires to the idea of filtering the unconscious. It’s the art of being in a movie that puts you in a capsule of intense magnetism. You could say that, to some extent, these films are about vanity. Transcendental style directors lose the meaning of objects and magical elements by themselves, which leaves a feeling of authentic reality. Perhaps this is the feeling that attracts the audience to the films of Ozu, Dreyer, Bresson, and Reygadas. With Reygadas, all of this manifests itself by bringing the lustful thirst of being in a world devoid of feeling. Carlos Reygadas chooses consciousness as his target, where the protagonist’s consciousness creates time.

The Mexican author says in one of the interviews:

My films are not spiritual, but human, which implies consciousness.[3]

Through human consciousness, Carlos Reygadas shows us the experience of being in a dualistic world between the profane and the sacred. It is this duality of the director that is interesting, which extends to his work and gives birth to a new cinematic experience. The feeling from childhood, state that you can’t name it. When there was no difference between peace and chaos – this becomes the driving force of his creativity. Reygadas is interested in a secret that is invisible in ordinary life. The mystery he discovers is revealed through the human consciousness that exists in the present and is involved in where it is and in what it is.

Between presence and absence, Carlos Reygdas chooses to be and is completely engulfed by this idea. It can be said that Precense is his life’s discovery. All true artists are excited about their discoveries and eager to share, and so does Reygadas. By sharing his films, he wants to show the audience the Inexplicable State that he experienced one day. Inexplicable State may imply different meanings: harmony, approach to the transcendent, magic, or the bliss of the unbearable lightness of being, which one day the director will drive away from the protagonist of Post Tenebras Lux, Juan.

The only thing I had to do then was just to live, now it was time for Ruth and Eleazar (children); It wasn’t nostalgia… everything around has come alive and everything is constantly shining, I feel like a child, it’s fresh after washing… clean – says Juan who survived death from the movie Post Tenebras Lux.

In Carlos Reygadas’ films, we see that Mexicans can be just as desperate as other people, even Europeans. Here, they are detached from the idea of God. In these films, only enchanting sounds and shots of flora and fauna are metaphysical, and in some cases, the author adds a magical touch with computer processing. The opening shots of the film Post Tenebras Lux will leave you spellbound – such are the lilac clouds at sunset, the reflection of the sky in a puddle, the clatter of a little girl’s boots, and the cascade of fog rising from the forest.

These seemingly banal scenes are an integral part of the daily life of a person, which can be felt only by being close to nature, and not in the concrete jungle. Long-term separation from nature cuts you off from feeling the duality of the world, this is not normal; Accordingly, man perceives the world in a kind of split state.

Carlos Reygadas is not interested in the representation of bodies. For him, bodies are small portals in which various human pains gather. In the movie Silent Light, Esther’s heart breaks from inexpressible pain. The director himself has experienced the unbearable pain caused by a broken heart. He knows very well how much emotional pressure the body carries [4]. Esther is not troubled by anger, jealousy, spite, or hatred. He accepts the futility of his life and continues to live, although his body cannot take it anymore. The pain accumulated in the young woman will burst forth in an instant, burst into tears, and break her heart. The body becomes a conduit for inner sensation.

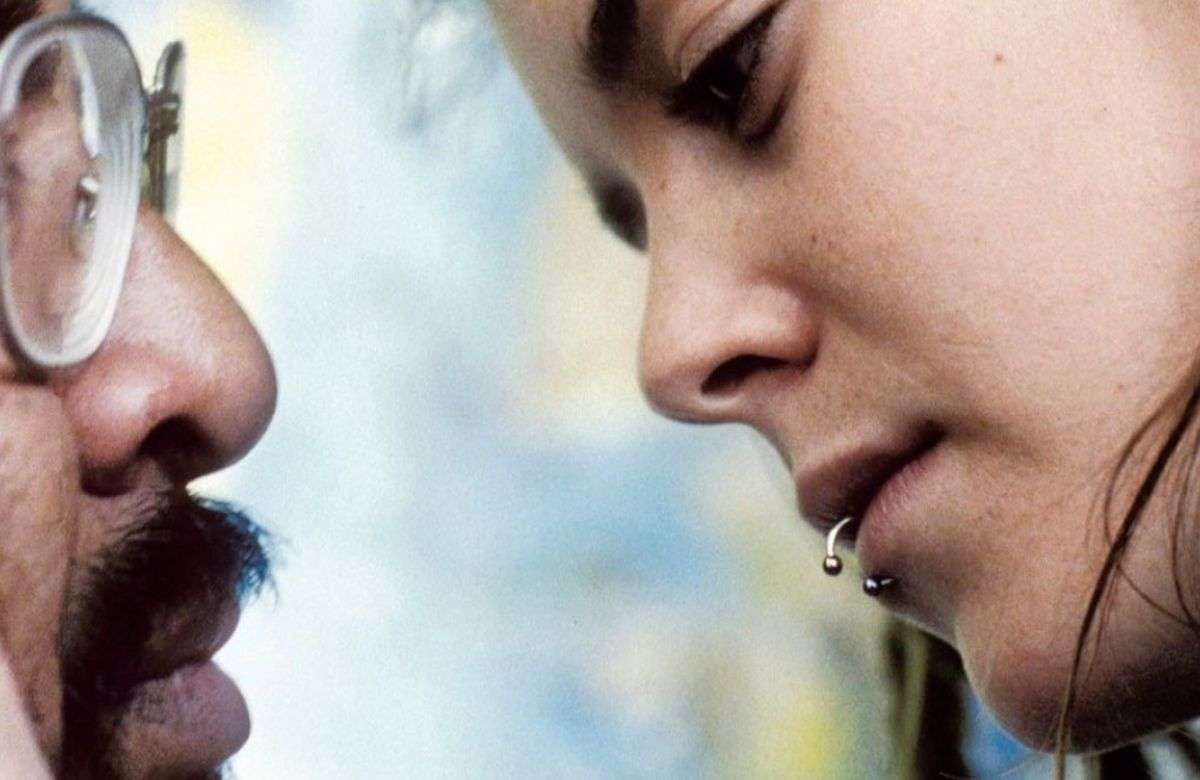

In the film Battle in Heaven, Marcos and his wife have a sexual act in a room where the Italian artist Messina’s painting of Christ The Dead Christ Supported by an Angel [5], it is hanging on the wall, and streams of blood flow from the pierced side of Jesus. In the film, the image of the Savior has become just another decoration, which has lost its sacred influence on the characters. The director, on the one hand, does not show God in a sacred way, although this does not mean that he manages to do this by showing a sexual act. No, it separates both events and presents the bodies of overweight Mexicans to a Western-influenced society that is foreign to mainstream films.

The owners of these bodies have the same human desires and needs as thin and white people. It seems that the husband and wife do not believe in God. Their lives are devoid of any religious value. Sex here is neither an expression of earthly needs nor does it imply the emotion of love. A poor Mexican couple kidnaps their boss’s child in exchange for extorting money, who dies. The film begins with a sexual act between an overweight Mexican man and an attractive young girl, which completely diverts the viewer’s gaze. This scene becomes a political act for society because it changes the perspective of the gaze, and the bodies that are common in mainstream movies are changed.

What is important in the film is the display of the desire for transcendence – the thirst for liberation that follows the commission of a serious crime. Throughout the film, the main character of Battle in Heaven, Marcos, strives for transcendence. He embarks on a path of desperation and wants to atone for his crime. Markos, dressed in white, enters the fog, wanting to confess his guilt. He merges into the fog, as a man sometimes disappears into himself, leaving only the feeling of the soul without the body. In this state, a person feels that he is only a soul and that the material world in which he lives means nothing at all; everything that happens beyond it is devoid of meaning.

At such times, signs lose their meaning and disappear without a trace in the flow of existence. Such a sense of the vanity of life creates a kind of transcendence with Carlos Reygadas. His cinema is imbued with the passion of simply being. His films show us that in the form of someone or something, some force can suddenly hit us and knock us to the ground, just as the feeling of guilt made Marcos sweat and throw him from one reality to another. He first climbs the mountain, looks around, comes down, and then his life changes. The protagonist of the film, Japon, also aspires to the top of the mountain.

As if by being in close contact with nature, the protagonists become sharers of some untold secret and embark on the path they need to walk in order to break free from the tyranny that the material world has to offer. Reygadas shows footage where religious elements or rituals are part of Mexican life, although his cinema is not religious. In the cinema of the Mexican author, spirituality is entered by the protagonist, although spirituality itself is not emphasized. It suggests not individual psychotypes or symbolic objects but a sense of unity beyond duality. This can also be called Dasein- Martin Heidegger, being in the world [6].

In the film Post Tenebras Lux, the director’s camera takes a wide shot, shows the main character in the middle, and blurs the image here and there. With this technique, perhaps knowingly or unknowingly, it indicates to us that the mind and heart, body and soul need to stop at one point; that is how the audience will experience what the director himself wants to convey to us – to be in the moment with all your essence, what he calls Being – just Being.

According to Heidegger, being is both the discoverer and the discoverable being, for it discovers itself as the essence in which it is discovered. Here, Heidegger refers to the discovery of the hidden, which is open to discovery [7]. Dasein can be an openness to the world and to oneself at the same time, culminating in the act of liberation, and aesthetically, it creates the clarity (purity) of shots in the cinema. The idea of Dasein is interestingly manifested in the dialogues of the characters with the director.

For example, in the film Post Tenebras Lux, a young man talks freely about his father’s sexual relationship with his sister, sharing the story and being emptied, and he, in turn, opens up to Juan and tells about his life problem – he has become too addicted to watching pornographic videos, which has disturbed his sleep and relationship with wife is messed up. Inner freedom, acceptance, living in the present moment, where personal traumas are not suppressed, not pushed into the future for resolution, this is an act of liberation. That’s what Reygadas wants to capture.

Carlos Reygadas leads to the act of transcendence in different technical ways. For example, the film Silent Light begins with a sunrise. The director directs the audience’s attention to the banal landscape of nature. The dawn scene most accurately portrays the cinematography of Carlos Reygadas. Aces and dices are repeated every day, but the picture is different each time, never the same. Reygadas’s cinema shows that there is something mysterious in vain existence, in vain repetition, which does not lose its charm, which does not become boring and surprises every time.

In one of the interviews, the Mexican talks about his own cinema and says that, like his heroes, we are all in similar situations in life. He adds Johan in the film is constantly unhappy, lonely, and suffering after the light goes down. He belittles everyone. In this way, he destroys others and himself. It represents a kind of status quo for people in the West. who are isolated from nature and others. And in the final, he experiences an Epiphany (Theophany in the Orthodox world). He feels something for his wife and recalls his childhood. Juan’s children are filled with a strong love for their parents, nature, and home, but they lose it as they grow up.

The Western world’s paradigm of life prevents people from being happy. In Mexico, as in the rest of the world, dominates this paradigm. Bodily shifts push the characters to an act of transcendence. French thinker Yves Ledur claims that the body naturally leads a person to transcendence and opens the way to the absolute. However, this transcendence goes downwards (towards the earth) and not upwards. Material existence directs one’s attention to the negative absolute – that is, death.

Then, with longing and desire, man is led toward the positive absolute, which is God – full of thirst for life. This is how the body recognizes the human purpose to move toward a transcendent act, where if Esther’s heart breaks, Samantha’s husband will cut his head off. However, these acts are not self-transcendence but a kind of jax between the self and the outside world [8].

In his films, the Mexican director diagnoses people who are lost in the modern world. The protagonists are disconnected from nature and God, and when they feel close to nature on a conscious level, a transformation begins in them through the physical body. There is a clash between the physical and the conscious, and they stand on the edge of life and death. Beyond them, we see shots of sunsets and sunrises, a rainy field, and a lily-colored sky reflected in puddles. We hear the meditative sounds of nature: chirping, the barking of dogs, the sound of horses’ hooves, the lowing of cattle, the wind, the rustling of leaves, the rustling of water, and the breathing of people.

At the same time, we see the chaos of the profane world: the chaotic flow of people in the subway, the streets of Mexico City, the party of the rich, the sweaty bodies in the baths. These scenes are as real and ordinary as natural landscapes. This opposition creates a kind of metaphysical order. Reygadas denies bringing spirituality into his films, but at the same time, it’s a miracle for him to wake up every day.

In an interview with Pavel Urbanik, he talked about his own feelings:

Every day, everything is solemn, mysterious and amazing; It is an inexplicable miracle that there is anything ordinary. I think that’s how life is: it’s full of miracles that we don’t see, maybe because we’re only interested in something when it’s scientifically difficult to explain. I wanted to blur the linear line between miracle and life and show life itself as a miracle. That’s why the opening scene of the film at dawn, children in the water, or just the circular motion of the car is as important to the story as the closing scene, which is full of wonders but is taken for granted.

If we call the manifestation of our consciousness in the world a ritual, it turns out that Carlos Reygadas himself becomes the creator of the ritual, whereby orderly repetitions of the reflection of vanity, he gives the films a sacred content and is directed toward the auditory- He wants to feel the viewer possibility of being concentrated in the moment, the feeling of the lightness of vanity, free them from the images and tailored (sticked)content that already exists in the environment. The normalized perception of reality allows Reygadas, as a representative of the transcendental style, to become a guide between man and the outside world or vice versa, between the outside world and man, where the conflict occurs only at the conscious level, while nature is the carrier of the balance(harmony) from the beginning.

Read More:

Why Are Michael Haneke Films So Disturbing?

Dariush Mehrjui: In Search of Lower Depths

K. G. George and the Craft of Flashback

Notes:

- A state of stability; a period during which little or no change occurs.

- https://cinexpress.ge/2020/05/07/%e1%83%a2%e1%83%a0%e1%83%90%e1%83%9c%e1%83%a1%e1%83%aa%e1%83%94%e1%83%9c%e1%83%93%e1%83%94%e1%83%9c%e1%83%a2%e1%83%a3%e1%83%a0%e1%83%98-%e1%83%a1%e1%83%a2%e1%83%98%e1%83%9a%e1%83%98/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7J3it0UH0qw7

- https://youtu.be/7J3it0UH0qw?t=3185

- https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/the-dead-christ-supported-by-an-angel/72db315d-b70e-42ed-86e0-42c86b665634

- https://ka.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E1%83%9B%E1%83%90%E1%83%A0%E1%83%A2%E1%83%98%E1%83%9C_%E1%83%B0%E1%83%90%E1%83%98%E1%83%93%E1%83%94%E1%83%92%E1%83%94%E1%83%A0%E1%83%9

- https://lolasphils.wordpress.com/2018/01/17/ყოფიერების-როგორც-უზოგა/?fbclid=IwAR3i1YRPdEJgrwasafvOo11eSMBvm5lwynozih5Lb0vP7zqIWtXa1DjZKuQ#_ftnref1

- https://www.persee.fr/doc/rscir_0035-2217_1991_num_65_4_3184_t1_0400_0000_2