Born in Warsaw in 1941, Krzysztof Kieślowski happened into cinema, by his own account, on accident. He had always wanted to be a theatre director but required a higher education to become one, so he tried enrolling in film school since that was the field closest to his desired occupation. By the end of the three years at film school, Kieślowski had broken up with theatre and fallen in love with documentary filmmaking. Kieślowski was attracted to documentary filmmaking because he wanted to depict reality accurately. Kieślowski made fourteen documentary films for the next decade, some with fictional elements. However, As the decade ended, he distanced himself from documentaries and pivoted to fiction.

During the production of a television documentary, “First Love” (1974), while filming an intimate moment the dad shares with his daughter, Kieślowski is struck by the obscene nature of his whole endeavor, how he had no right to violate a real person’s privacy like that. Hence, the ethical limitations of documentary filmmaking marked his shift to fiction to get closer to ‘depicting the truth.’

The following list ranks the feature films of Krzysztof Kieślowski, the body of work he is most known for in the world after his transition from documentary filmmaking to fiction. His documentary work is vast, obscure, and remarkably distinct from his fiction works, yet he maintains a solid singular personality that deserves a separate list of its own.

11. Blizna (The Scar, 1976)

Based on a short story by Romuald Karas, who also wrote the screenplay with Kieślowski, “Blizna” is about an honest communist cadre, Stefan Bednarz (Franciszek Pieczka), who genuinely wants to do good for his home-town, and believes in Communism, and the promise of the Party to do good for the people. Being a famous native of his hometown of Olecko, he is made the director of a factory that has recently begun construction and must preside over its affairs. Vast stretches of forest are cleared in this primarily agricultural town to make space for setting up the factory.

Riding in high spirits of rapid industrialization and development, he soon finds himself at an impasse when the locals present their resentment and unhappiness at what they see as outsiders’ intrusion in their perfectly happy lives. A man of the people, Bednarz initially tries his best to be fair and address everyone’s grievances. Still, as discontent grows among the people and pressure from the Party who disagree with how he handles dissent, he finds himself in a sensitive situation with the dreadful feeling of losing touch with his essential self and corrupting his soul.

The film’s central conflict is, naturally, CHANGE. By pitting conflicting perspectives against each other, this narrative extraordinarily dramatizes the age-old philosophical problem: “What is ‘good’ and ‘bad’? How does one know? Who decides?” This conflict is at the heart of the auteur’s oeuvre, and later, “Dekalog” comes closest to providing an answer.

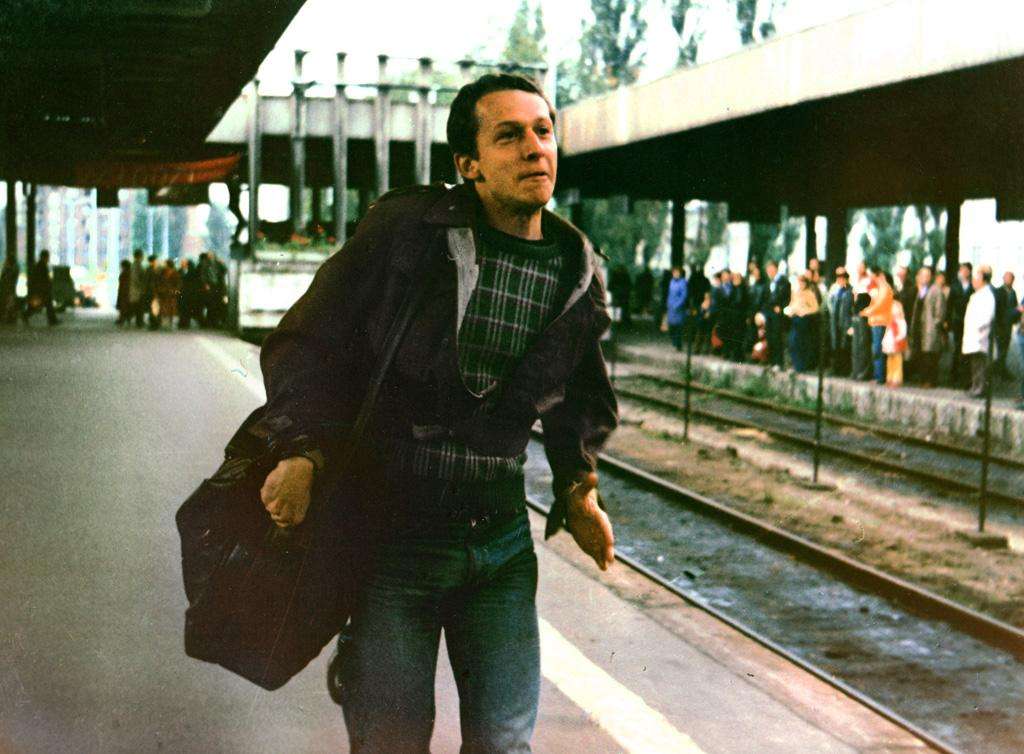

10. Przypadek (Blind Chance, 1987)

This movie was made in 1981 but was not given a theatrical release until six years later, in 1987. Kieślowski’s first film under martial law was also his biggest head-on collision with the Censors, who outright blocked its release and later put out heavily censored versions. Witek, played by Bogusław Linda, is a young man who remembers even when he came out of his mother’s womb. We see Witek grow up and make and lose friends and girlfriends until he joins medical school. Upon his father’s death, Witek loses his motivation to become a doctor, drops out of medical school, and decides to catch a train for Warsaw. Having followed in a straightforward manner Witek’s life so far, the movie takes a uniquely Kieślowski-an turn, as it shows, in succession, the three paths and trajectories of Witek’s life based on whether he caught the train.

There are three versions of the same story: one on the ‘this’ side, one on the ‘that’ side, and one on the outside. In all three versions, Witek longs to leave the country. But always falls short of doing so. In the first instance, when he is arranged to go to Paris with a Party delegation, their flight is canceled due to a strike. In the second version, Witek, now having associated with not only the Underground rebels but also a professed Catholic, is denied a passport by the authorities.

Then, in the third instance, as a good-natured, career-driven, neutral outsider, he finally makes the plane to Egypt for a medical conference when the plane explodes after taking off. In all the three possible ways Witek’s life could’ve gone in, as a member of the Party, as a member of the Underground, and as a neutral, ‘apolitical’ outsider, Witek was fated not to leave the country alive.

This movie can then be seen as a frustrated cry of a claustrophobic artist who felt trapped in Poland’s rigid, authoritarian government at the time. It is a constant tussle between fate and chance. The central question, of course, is whether things happen for a purpose, or even a reason, or if there is no larger context or meaning to them, and all life is ‘blind chance.’ Kieślowski first highlights and underscores the immediate anxiety of the uncertain political climate of life under Martial Law while at the same time undermining these political concerns for far more important spiritual and philosophical problems.

9. Three Colors: Blue (1993)

Riding high on the success of filming the Ten Commandments, Piesiewicz and Kieślowski reunited, this time in France, to film the values of liberty, equality, and fraternity. However, unlike “Dekalog,” Kieślowski has unambiguously declared which film corresponds to which value. “Blue” is about Liberty. What does it mean to be free? Or rather, what it means to be liberated on a personal level? Julie is the recently widowed wife of a popular and well-respected contemporary music composer. In some ways, she’s been given a new life, a liberty, to live her life as she wishes, as much as she must mourn the death of her husband and child. This tender contradiction is so diligently and carefully portrayed throughout the film.

However, unlike earlier Kieślowski films, there is little interference or help from fate. This is a rational world, not ruled by the Commandments of religion but by the ideals of men, and one cannot help but notice a strong sense of irony that runs throughout “BLUE.” We do not know much about Julie’s husband or her child, and we do not feel much about their brutal accidents either. All we know about her husband is that he was a famous music composer commissioned to write a Concerto for Unified Europe, and he had a pregnant mistress. The completion of this concerto by Julie, left incomplete by her husband, marks the film’s end.

“BLUE” is not so much about a tragedy or mourning but about the immediate aftermath of a horrific incident on a personal level. As Zizek points out in “The Fright of Real Tears,” it is precisely after the musical score is completed, after she has slowly ‘returned’ to ‘real life,’ that she can begin the process of mourning.

8. Camera Buff (1979)

Released in 1979, “Camera Buff” is an autobiographical piece not in the sense that it sheds light on some personal instances from Kieślowski’s life. Still, it is the mythic tale of the artist, every artist, who finds himself wholly seduced and at the mercy of this demanding, unrelenting muse, who wants nothing less than the sacrifice of the whole being of the artist. Filip Mosz buys a camera to film the first memories of his newborn daughter so “she can watch herself grow.”

We see the natural awe and wonder at the existence of a camera and how little and ordinary moments are captured, compressed, and then squirted into a larger recreation. Then, there is also the natural anxiety and self-consciousness that comes upon seeing a camera pointed at you. When Mosz films two Party Nomenklatura as they come out of the meeting room to go to the washroom, they freeze in their steps when they see the camera. This is soon followed by the demand to delete that footage.

When Mosz buys the camera, everyone around him is happy and curious, looking at it with eyes full of glee, curiosity, promise, and wonder. One cannot help but wonder whether this was also the reaction in Moscow in the ‘20s when Dziga Vertov sat down on the streets with his camera. From the beginning, his wife is suspicious of this new toy that has come their way. She grows increasingly frustrated as she feels growingly neglected and alienated by her husband, especially when they’ve had a newborn daughter.

Eventually, after his wife leaves him, the distraught Mosz has only one thing left to do: turn his camera on himself, marking complete absorption, completing the circle, and turning his personal tragedy into a comedy, albeit a dark one. This is a seminal work of cinema, Kieślowski’s third fictional feature film, marking the transitional point in his career when he switched in full gear from documentary to fiction filmmaking.

7. Three Colors: White (1994)

After being humiliated and divorced by his ex-wife for being impotent, stranded, homeless, and without money in France, Karol Karol illegally smuggles himself back home to Poland in a hilarious sequence. The newly capitalized Poland is the perfect place for a young opportunist like Karol Karol, and through a series of elaborate schemes, he makes himself a prosperous businessman. In a sick twist, however, Karol Karol makes a will, leaving everything to his ex-wife, and then fakes his own death to lure her to come to Poland. At his funeral, he watches her cry from afar. Later, when she comes home, she finds Karol sitting in bed. They finally make passionate love.

In the morning, however, Karol Karol leaves before she wakes up, and Dominique is arrested for the murder of her ex-husband. The film’s closing scene is Karol Karol going to prison to meet Dominique. He stops in the prison compound, looks at her through the window, and starts crying. She says, “I love you,” in sign language.

“White” is about Equality. On a personal plane, this film explores the idea of equality in a romantic relationship. One cannot help but ask, can there be true love among two people who are not equals? Wouldn’t the more powerful in a relationship, inevitably, unintentionally even, end up using the less powerful? Dominique says she doesn’t just love Karol; she needs him. And so she desperately tries to provoke him by humiliating him. Karol’s whole elaborate journey is to get back at Dominique, level the score, and get even. When Dominique finds that she has been played and Karol successfully gets his revenge, their twisted love for each other is rekindled.

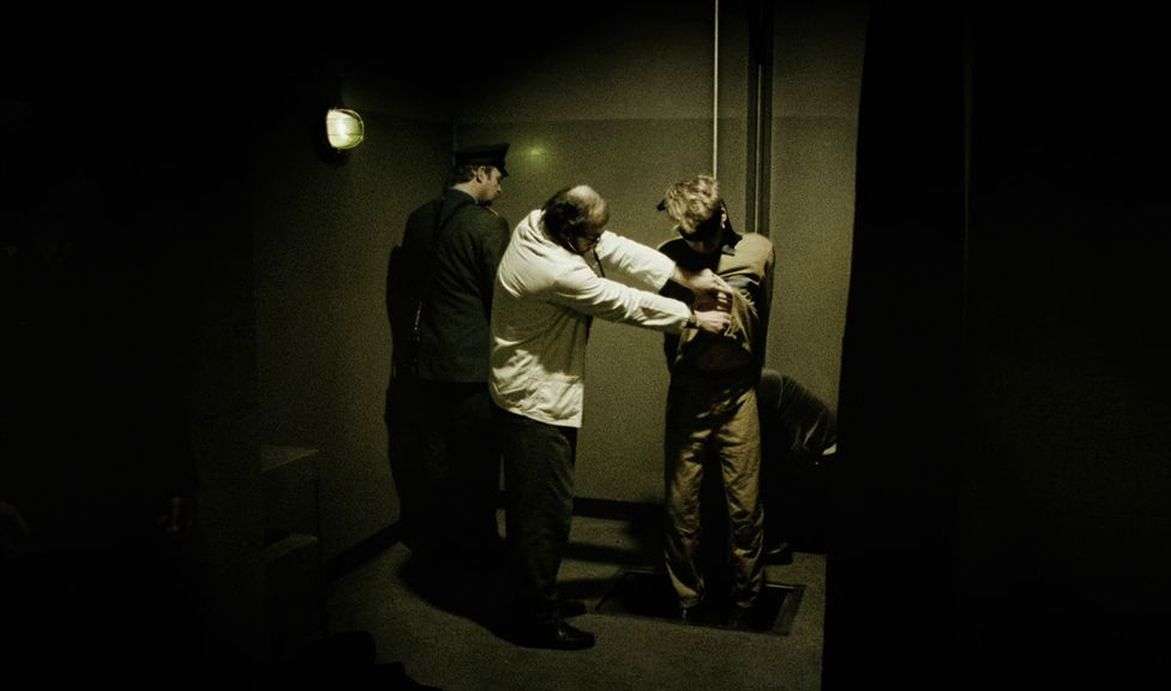

6. A Short Film About Killing (1988)

This is a damning depiction, a cautionary tale of urgent proportions, Kieślowski holding the mirror to society and exclaiming, “What are we doing!” much as how the young lawyer does at the very end. Waldemar, the cabbie, is not the kindest man around. He is mean to people for no reason. We see him feeding a dog, but later, he scares another. He likes to keep his car clean, which can sometimes assume obsessive levels. He particularly refuses a ride to a couple from the same apartment complex, out in the cold, when he had no reason to.

Jacek is a typical teenager, aimlessly roaming about Warsaw’s depressing, gritty, green streets. He carries with him a miniature portrait of his kid sister. The stories of Jacek and Waldemar, the cabbie, are intercut with a third: Piotr Balicki, a young, eloquent lawyer, being interviewed for the public defender post. The ideas of justice, mercy, and forgiveness start here, from the first act itself, juxtaposed with the unreasonably unjust acts of both Jacek and Waldemar. All of this culminates in the famously long murder sequence. Aptly named “A Short Film About Killing” by juxtaposing two cold-blooded murders side by side, one by an impulsive teenager and another by the stable, mature state machinery, this is one of the most damning indictments of capital punishment and perhaps the longest ninety-minute film one will ever see.

The film’s uniquely bleak look and texture are entirely owed to the cinematographer, Sławomir Idziak. Rarely has a European movie made such use of negative space and vignette in a medium-budget feature film. It is bold and daring, and it pays off big time. Idziak would again use his magical green touch three years later in “The Double Life of Veronique,” this time in Paris, and for a more poetic effect.

Also read Related to Krzysztof Kieslowski’s Movies: Odes to the Silver Screen: 10 Cinematic Love Letters that Transcend Time

5. A Short Film About Love (1988)

Like the above, “A Short Film About Love” is the extended, feature-film version of “Dekalog 6.” Tomek is a young boy who lives with his grandmother and spies on his neighbor, Magda, an attractive yet much older woman. This starts as a typical stalker tale. However, the movie switches gears when Tomek confesses to spying on Magda, and soon they are in conversation. She gets more interested in him as she learns more about him. This naïve, inexperienced young man claims to be in love with her, while she, on the other hand, a mature woman, has grown disillusioned with the idea of ‘love’ and doesn’t believe it exists. Magda takes Tomek home and sexually humiliates him, pressing the point that there is no love, only lust. Tomek pushes her away, runs home, and slashes his wrists.

“A Short Film About Love” differs entirely from “Dekalog 6” in its ending. In the film version, Magda sees that he has returned from the hospital and decides to meet him at his apartment. He is asleep, however, and his grandma asks her not to wake him. She sees his telescope, with which he peeps at her. She sees through it into her apartment, then closes her eyes tight shut, and sees herself on that night when she came home, distraught, and spilled the bottle of milk. But this time, from behind comes Tomek, who warmly puts his hand on her shoulder, thus completing the circle.

This is a uniquely Kieślowski-an film. Here, the voyeur becomes watched, and at one brilliant moment, both stalker and stalked are stalked by a third person. Looking is a recurring theme throughout Kieślowski’s films. There is a strong sense of someone watching, watching closely. It’s a movie about faces, gazes, subtle expressions, and eyes. Grażyna Szapołowska as Magda and Olaf Lubaszenko as Tomek delivers a rare synergy. This mysterious exchange goes on without words, and we are kept at the edge of our seats, gasping. “A Short Film About Love” is perhaps the most tender film Kieślowski has made.

4. The Double Life Of Veronique (1991)

The film opens with a low-angled close-up of a woman singing at an outdoor concert. We pan back to a wide shot as she sings a prolonged note. This is Weronika, a Polish woman with a gifted voice. She has a lover, a father, and a sick aunt in Krakow. She tells her father, “I feel like I’m not alone in this universe.” Later, in the streets of Krakow, she sees someone who looks like her climb onto a bus. Her innocent smile is on her face, of child-like wonder and contentment. Her intense feeling is confirmed. Weronika auditions for a conductor in Krakow, and her husband, who directs operas, is instantly selected. During the central performance, however, she mysteriously collapses and dies.

In France, Veronique, a music teacher, is overcome by a sudden wave of grief in the middle of passionate sex. From here, we follow her life, which has interesting parallels and coincidences with the dead Weronika. She goes to her music tutor’s home and tells him she won’t continue her training for any reason, just an intuitive feeling. Veronique teaches her students the music of Van den Budenmayer, the same music the Polish Weronika performed before her death. She tells her father she felt like she lost someone on the same day Weronika died.

What does it mean, though? What connections do the French and Polish Veronique share? Are they doppelgängers? Are they the same person? How does one feel about what has happened to the other? There are no answers to these questions. It is merely a celebration of those freaky, deja-vu moments we have all had at some point in our lives. Incidentally, this is also Kieślowski’s first production outside Poland. Is it not unreasonable, then, to see the story as a metaphor for Kieślowski’s state of mind? Krzysztof Kieślowski did indeed die of a heart problem in Poland, but we are yet to find his French counterpart. Maybe on the morning of 14th March 1996, they felt the strong, inexplicable urge to quit filmmaking.

3. No End (1985)

“No End” is an intensely harrowing, heart-wrenching film, a drama of the highest stature. This is the first film, the beginning of many future collaborations of Kieślowski with screenwriter Krzysztof Piesiewicz and music composer Zbigniew Preisner. Several themes that become central in the later Kieslowski films are seen in their infancy in this film. Urszula is a recently widowed wife of a human rights lawyer whose pending cases come to haunt her. Made in the middle of the peak of political turmoil during martial law in Poland, this film did not face a fate like “Przypadek.” However, it was panned by the Party, the Church, and the Underground.

This movie is rightly compared to Kieślowski’s later film, “Blue.” “Blue” is also about a recently widowed woman who grapples with her bereavement. Like Julie is thrust to complete her husband’s concerto, Ursula in “No End” is forced into her husband’s case. Like Julie, Ursula tries everything to forget and set free from her past. However, while Julie finishes the musical score and hence successfully re-enters ‘normal life,’ the pain is too much for Ursula to bear alone, and she turns inward and subsequently kills herself to reunite with her husband. Unlike “Blue,” there are no layers of irony in “No End.”

This is a straight, bleak tragedy expressing unfiltered, pure grief. It is almost as if the depressing, dirty-green, communist, martial-law Poland was the perfect environment for one to mourn someone’s loss properly. At the same time, Paris’s free Western European landscape is too overwhelming for one to grieve appropriately. While “Blue” is a French story, “No End” is uniquely Polish. Hiding in the shadow of the behemoth “Dekalog,” this is a rare masterpiece of Polish cinema, a cornerstone of the essential Kieślowski oeuvre.

2. Dekalog (1989)

What is missing from most discourse on “Dekalog” is its place in Kieślowski’s oeuvre. The whole of “Dekalog” is always taken separately from the rest of Kieślowski’s films, similar to how “Berlin Alexanderplatz” is taken independently from the rest of the body of work of Rainer Werner Fassbinder, another great European filmmaker, taken too soon. Conceived hot on the heels of the controversial reception of “No End,” the story is well known: Piesiewicz, with his unquenchable thirst for trouble, proclaimed: “Someone should make a movie about the Ten Commandments” and the ever so eager filmmaker took it up as a challenge wondering “how does one film the Commandments?”

Ten one-hour-long movies of great emotional depth and sensitivity cannot be compressed into this list. Each part of Dekalog deserves its own essay, and indeed, there is no shortage of scholarship for any episode. In his book, ‘I’m So So,’ Kieslowski calls “Dekalog” ‘stories of people who slowly realize that they are moving in circles,’ not unlike the characters of “No End.” However, unlike the characters of “No End,” the trials and tribulations are more personal and spiritual.

As Slavoj Zizek correctly points out, “Dekalog” should be admired for its saint-like resistance “to scoring easy points by spicing up the story with dissident thrills.” As “Camera Buff” marks Kieślowski’s transition from documentary to fiction, Dekalog marks his oeuvre shift from the political to the spiritual. Conceived for television, “Dekalog,” viewed at home on a big screen in solitude, makes for a spiritual experience, much like reading a great novel that transports you into another world.

1. Three Colors: Red (1994)

“Red” is the last movie Kieślowski made before he announced his retirement, the concluding part of the “Three Colours Trilogy.” This was the movie his body of work and his entire life led to. Valentine, a model, on her way home from work, runs over a dog, whose home and owner she tracks with difficulty. It is an old man in a large house who couldn’t care less about Irene or his own injured dog. He is obsessed with his illegal hobby of spying on his neighbors. Valentine’s repulsive curiosity about the old man gradually brings them to familiar terms, and we learn he is a retired judge.

Auguste is a young lawyer preparing to become a judge. He is Valentine’s neighbor, and though it is strongly hinted that the two will somehow meet or that their lives will intersect, it never happens. He crosses the same street Valentine drives by when one of his textbooks falls, opening a relevant chapter in the criminal code, which happens to be the one that also comes in the exam. The parallels between the young and old judge are too similar for one to conclude they are simply the younger and older versions of the same person. As Valentine crosses paths with Auguste throughout the film but never meets him, the old Judge, too, laments for never meeting ‘the one’ or even meeting Valentine forty years ago.

If “No End” is the thematic companion to “Blue,” “Red” is the thematic companion to “Blind Chance.” The central theme explored in “Blind Chance” is the blind hand of chance, randomness. A mere difference of a second would lead to a chain of events wholly opposed to how they unfolded. Real life poses an endless stream of ‘what ifs’. In “Blind Chance,” Kieślowski directly plays god by blocking the narrative halfway and starting over, yet the protagonist ends up with the same fate in all three scenarios. For all its random, blind chance, a dreadful sense of fatalism looms throughout ”Blind Chance.”

“Red” is not a Polish story but, again, a French one. It is full of characters who cross each others’ paths but never meet, leaving us to wonder, “What if they did?” While in “Blind Chance,” most characters cross each others’ lives in one version or another, in “Red,” they are deliberately kept apart. While the Kieslowski of “Blind Chance” made the plane explode, the Kieslowski of twelve years later gave the people on the cruise a second chance. “Red” can hence also be called the anti-Kieślowski film. No fatalistic hand sways the narrative here, nor are there any double lives. Here, life merely plays out as it does, and we are invited to speculate till we pull our hair out.