.The less said, the better about the last year – 2020. It started with an Oscar euphoria – Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite clinching the most Oscars at the 92nd Academy Awards, including the historical win at the Best Picture. However, soon it turned into a macabre paranoia. Lockdown, rightfully, let to shutting down the theatres. Film festivals went online. All the blockbuster films of 2020 were left with no choice but release it on OTT platform.

Recommended – The Best Films of 2020

Midst of this, my enthusiasm for contemporary films, especially the ones released in 2020, was dwindling to the point of exhaustion. Of 440 films, I only watched 50 films from 2020. I took the help of classics to sail through the bad year. I was specifically interested in Japanese films. Started my journey into Japanese cinema by rewatching films of Kurosawa and Ozu. Gradually, I moved to Kenji Mizoguchi, Masaki Kobayashi, Hayao Miyazaki’s filmographies.

Then recently, I discovered Mikio Naruse and Hiroshi Shimizu. Their films largely dealt with the post-war socio-economical structure of Japan. While Japanese New Wave, unfortunately, overshadowed by the French New Wave, New German Cinema and the Hollywood Renaissance, often criticised the political and regressive social structure of the country.

Here, I have listed some of the best films that I watched in 2020, which I strongly recommend. Buy it, steal it, illegally procure it, do whatever you can, but do watch them. For the list of the best films I watched in 2020, I have only considered my first watches. You can follow me on Letterboxd.

Funeral Parade of Roses [1969, Toshio Matsumoto]

Without any dramatic countdown and masturbatory waiting, let me reveal the film I loved the most last year – Toshio Matsumoto’s pop-art masterpiece Funeral Parade of Roses. It’s a savage ride into the hedonistic and lawless landscape of sexual and artistic freedom of a foregone culture. Far from the current social and political conservatism, is an intoxicating affair, loosely spun together with a modern queer re-imagination of the Oedipus myth. Highly evocative visuals coupled with provocative narrative draped in a mix of quasi-realism & fantastical elements, without any heed to moralistic nature of society, is a beauty to behold.

Apparently, certain elements of “Funeral Parade of Roses” inspired, in your face, lasciviousness visuals with strong violent undertone on Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange. However, Funeral Parade of Roses is not merely an exercise in a radical narrative for provocation, underneath all, it deals with the identity crisis of a transvestite – Eddie and the cultural understanding of the gay and transgender community.

Stream Funeral Parade of Roses on MUBI

High and Low [1963, Akira Kurosawa]

Akira Kurosawa’s nerve-wracking thriller ‘High & Low’ comes close to the Funeral Parade of Roses. Adapted from Ed McBain’s crime novel “King’s Ransom,” the masterstroke of Kurosawa lies in the title he selected – “High and Low,” it could befit the class divide he nuanced explores in the garb of a procedural thriller or it could also point to the fact that the detectives search high and low areas to catch the kidnapper.

Kurosawa isn’t interested in pulling off a twist, which he could have given how the first act establishes the dirty corporate politics, Kurosawa isn’t interested in grandeur, he simply makes characters, their morality and their choices tangible for us to experience their fear, the stakes and their constant dilemma. He captures their vulnerability and insecurity in a way that is hardly captured. This is one of the greatest thrillers – taut, tense and rich in detail. It had me sweating in the third act. I would double bill this with Robert Bresson’s masterpiece “A Man Escaped.”

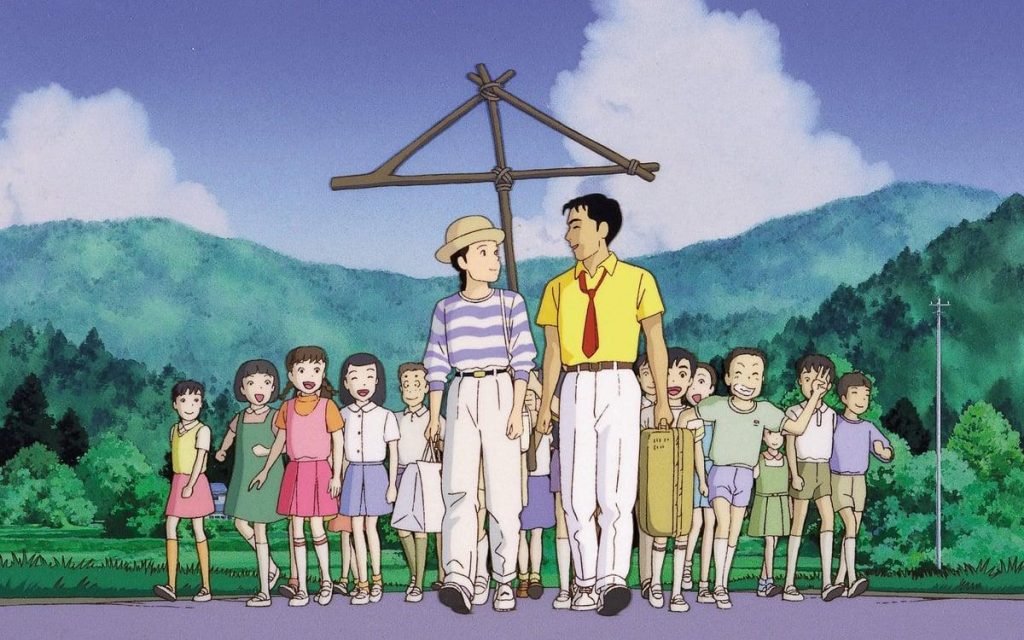

Only Yesterday [1991, Isao Takahata]

“Childhood is the kingdom where nobody dies.” ―

Our childhood memories – be it tragic, traumatic and/or the happy ones- we carry them inside us, throughout life, as if they extend our body. They carve our soul; they mould our being. It often shapes our being and purpose, makes us who we are as adults.

Isao Takahata’s ‘Only Yesterday’ tells one such emotionally complex yet poignant, intimate story about a youthful girl reflecting on her childhood memories. The 27-year-old Taeko Okajima was once a child with artistic flair and dramatic ethos. You give her a wing, she would fly high.

The film deals with complicated feelings stemmed out of a knot of unresolved, unfulfilled and, sometimes, unanswered and futile events. Whenever we revisit our memories, we try to disentangle the knot to seek an answer to our spiritual & personal crisis.

Taeko, who works in Tokyo, takes leave for ten days to go on a vacation to the countryside. The film does not inform us about her current living condition, her emotional state and her relationships. We subsequently learn about her life through flashback scenes that she reminiscence in the train. Does it over the ten days radically change her life? No. Does it answer her existential problems? No. Takahata isn’t interested in binary resolution, because there can’t be one. However, a better perspective leads to a slight untwining that gives Taeko a better grip on her life. The film equally deals with the ethical relationship with nature which seems threatened after modernization.

‘Only Yesterday’ will exhaust you emotionally, leave you thinking, and invigorate the warm, cushy and nostalgic memories of childhood.

Recommended – The 10 Best Hindi Films of 2020

Three Sisters [2012, Wang Bing]

What if children are left untouched by the glorious kingdom of childhood?

Wang Bing’s meditative drama ‘Three sisters’ is an unflinching but compassionate look at the lives of three sisters in rural areas of China, far from bustling cities, booming economy and mobile-addicted society. They are devoid of basic child rights – the right to survival, protection and development.

Wang Bing’s patiently draws state of rural communities in China seems to exist a century behind. Detached from the modernity, three sisters, under ten, navigates their childhood doing simple chores, in the absence of their mother. Mother has runoff, as their father claims, with a man to a city. When the elder of three sisters is left back at home, with his grandfather, while his father left to a town in search for an opportunity with younger two sisters, she reflects on the bleak future, realizing how cruel it gonna be. It’s tragic and heartbreaking, but she makes peace with it.

Pastoral: To Die in the Country [1974, Shūji Terayama]

Does recreating the traumatic memories of childhood turn it into the work of fiction?

“The whole past is just fiction,” says a filmmaker who tries to understand his childhood by making a film. It’s a meta-film. It’s a trippy ride in the memories of a filmmaker. Often studded with phantasmagorical visuals where reality and fiction intersect, falling outside the linear timeline. When you reconstruct your childhood from fragmented memories, exaggerating the details, forgetting the specifics and timeline, the reality starts blurring. Does it violate the existential experience of your past? Does it make your past a work of fiction? The film tries to raise this pertinent question about how our memories of past influences our present.

If you find it baffling for the most of the film, don’t be surprised, the cultural and political nuances will be difficult to decipher, but let the surreal visuals register first, let the boy navigate you through the conundrum of his life. Let the absurdity surprise you. It’s a difficult film, and there’s no shame if you don’t comprehend it completely, because you won’t. However, it should be an essential watch for all.

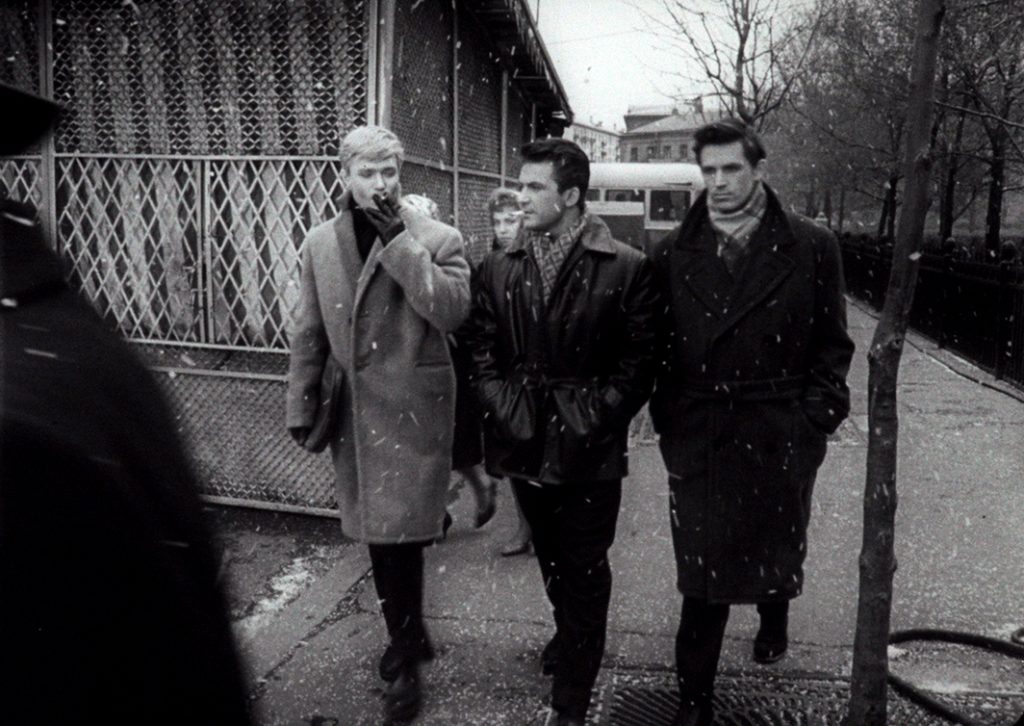

I Am Twenty [1965, Marlen Khutsiev]

Youngsters knee-deep in a postwar existential-crisis.

The film utilizes the usual trope of coming-of-age dramas; however, what really set this film apart is its sincerity and conscientiousness in representing the societal transition of Moscow city, the people inhabiting it and their struggle. Post Stalin’s death and the postwar, city is invigorated with new possibilities and energy, offering an extraordinary experience of self-discovery. The tension between stillness in life and everything in motion around them embodies the young people’s inner conflicts. It perfectly captures the hope and disbelief –and growing cynicism–that characterized this period in Russian history.

A Moment of Innocence [1996, Mohsen Makhmalbaf]

Children saving mankind, saving the cinema!

At the age of 17, Mohsen Makhmalbaf was jailed for six years for stabbing a firearm security man during a protest against the imperial Iranian government. He wanted to save mankind along with his love interest. After he was released from the jail, he pursued his career in filmmaking. Film-makers, in a spiritual way, save mankind as well. In 1994, on a fateful day, while searching for non-professional actors for his upcoming film, he met the firearm man again and decided to make a film recreating the episode.

“A Moment of Innocence” is an autobiographical drama that packs philosophy, allegory, romance and perhaps, the most beautiful camera freeze moment in the history of cinema. It achieves everything mentioned under 75 mins that most of the filmmakers fail to achieve in their career. Rarely, I have seen someone blending fiction with reality in such a beautiful way. Do yourself a favour and watch it right away.

The Best of Youth [Marco Tullio Giordana, 2003]

Like an expansive, rich and epic novel, the story of two brothers unfurls from the tumultuous 1960s to the start of the 21st century.

Marco Tullia Giordana’s six-hour sweeping saga weaves together the strands of the political and the personal that patiently unfurls from the tumultuous 1960s to the start of the 21st century. It offers immense pleasure to sink deep into its sprawling drama of two brothers of an Italian family. You meet them in their youth, at their prime, both excelling in their studies. You grow admiring them. When they digress due to prevalent socio-political ideology, you feel their anguish. With every relationship, be with friends, relatives or strange, we sense their foibles, spirits and their insecurities.

The intimacy & nuances it offers blurs the line between the screen & reality. It brings us so far inside the characters that you feel they are your own. We experience the sad and wondrous episodes like it is happening to us. The tragedy feels personal. The joyous moments fill you with giddy happiness. And as we approach the end, we wish it was longer. Or at least we could meet the characters on a Sicily beach. I wish.

The Ascent [Larisa Shepitko,1971]

It is youth that must fight and die in a War.

‘The Ascent’ is a multifaceted character study of individuals caught in the middle of war & the war within. Shepitko avoids the usual gruesome battle sequences and the displays of gallantry to settle for an intimate exploration abetted by the minimalistic setting. Through the showcase of psychological and the very physical toll of war on the characters’ conscience, Shepitko bestows a heavy burden on us.

Set during World War II, shot on grainy black and white stock, the film looks like a product of its setting than the time itself, and that factor renders even more believability to the grim events unfolding in it. Read our review here.

Z [Costa-Gavras, 1969]

A persistent feature of the political landscape leading to a revolution – An Assassination.

The cynical events unfolding in director Costa-Gavras’s “Z”, a pulse throbbing thriller cranked up Mikis Theodorakis’s kinetic score, feels the most relevant film mirroring the current political milieu. A left-wing activist turned politician is publically murdered, in presence of Police – head of security & General. It is haphazardly declared as an accident until the case itself unravel, in presence of a tenacious magistrate.

Z is a political war cry that’s deafening, for how real it feels, and equally thrilling. But Costa-Gavras peppers it with tongue in a cheek humour to convey his political stance. Well, the film got Costa-Gavras banned in Greece including crew members and the letter “Z” in any graffiti.

The Battle of Algiers [1966, Gillo Pontecorvo]

A political uprising to liberate the nation from French, and taking what’s rightful of Algerians.

Considered as the seminal work of war genre, “The Battle of Algiers” strongly instituted a cinematic vocabulary that influenced several filmmakers including Oliver Stone’s JFK, Kathryn Bigelow’s Zero Dark Thirty and Anurag Kashyap’s Black Friday. From the use of shaky hand-held cameras, a quasi-documentary to shooting in real-life locations with real people, the influence of Gillo Pontecorvo’s style is evident in almost all modern war movies.

The film clinically studies the legacy of imperialism as an issue and disease that always set the brutish cycle of attack and counterattack in motion. How the insurgents rise against the imperialistic forces like a cult and their guerilla tactics are explored in the film. It examines the Algerian uprising (initiated by insurgents FLN) to independence from French colonialism during the late 1950s and early 1960s. And Pontecorvo’s narrative strength lies in his unprejudiced sketch of characters and events, embracing the moral ambiguity of characters and dualistic dichotomy.

Napoleon [1927, Abel Gance]

Battles give us a hero as well.

Abel Gance’s astonishingly ambitious biographical drama on Napoleon is a force to reckon with. Its gargantuan length and scale, unbelievable technical wizardry it boosts, and heart-pounding orchestral score from Carl Davis consume you from the word go. This silent epic, which reportedly ran for nine hours in its original cut and was conceived as merely the first film in a six-part biography, did not only push the boundaries of filmmaking but it institutionalized the filmmaking itself.

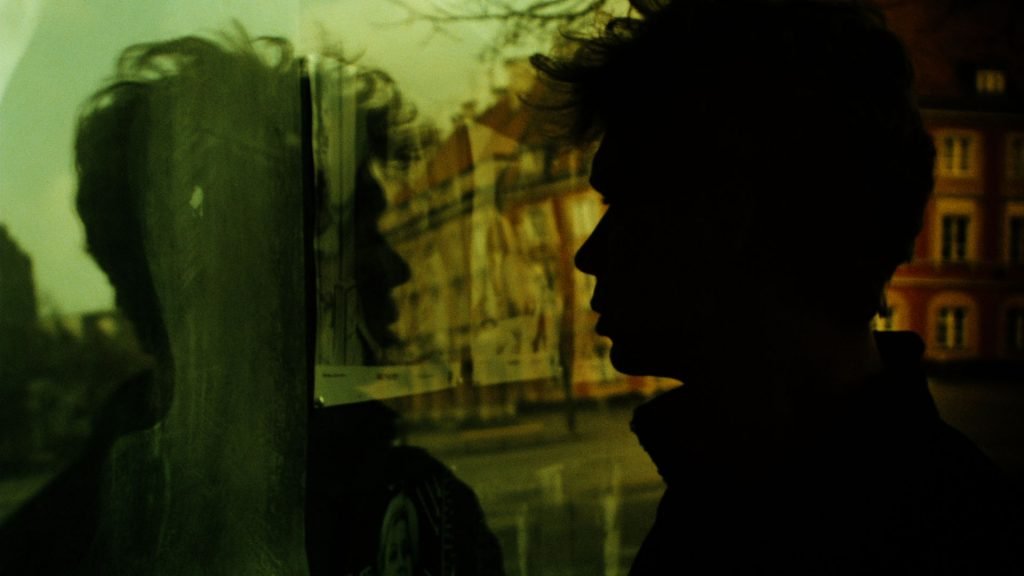

A Short Film About Killing [1988, Krzysztof Kieslowski]

A film about killing & murder...

I still can’t shrug-off the horror of both – the killing & the morality around killing. Krzysztof Kieslowski’s film is a disconcerting drama about killing than the killing itself. It reflects on the unsparing and irredeemable civilized society we live. What further magnifies the disturbing elements in the film is our morbid curiosity for capital punishment attuned to our voyeuristic impulses.

Why do we prohibit killings but vote for capital punishment? Why the cycle of human violence fascinates us the most? The paradoxical lust for violence and ironical implication of committing a crime are explored in a gut-wrenching narrative of the film, which brazenly avoids moral lecture. With this film, Kieslowski offers a powerful artistic protest against capital punishment. This can be double-billed with another subversive critique of capital punishment – ‘Death By Hanging’, directed by Nagisa Oshima.

Stream it on YouTube

Death By Hanging [1968, Nagisa Oshima]

Why state-organized death by hanging not a murder?

A significant figure in the Japanese New Wave, subversive Nagisa Oshima made one of the most contentious, anti-establishment film that challenges the subjective idea of crime and objectively criticises the bureaucrats & law-men tasked with upholding the governing law.

He lays bare the hypocrisy of such authoritative figures. The sanctimonious functioning of such body. And, how ignorant they are to the plight of guilty people. He does a clinical examination of crime and tries to put forth the genesis of it, and he does that in the reverse order. We are already informed about the punishment in the opening scene – death by hanging if the title didn’t make that clear.

The failed execution of hanging ensues the farcical re-enactment of the crime where we learn about the crime. There’s no point hanging a convict if he can’t remember the reason for his punishment – it’s unlawful and morally reprehensible, or maybe not. The reenactment reveals how rotten the law-men are and their superficial idea of crime. It’s downright hilarious seeing them being racist, obnoxious and dimwitted. It slowly drifts into metaphysical reality having delirious, absurdist undertone to it.

Read the review of Death By Hanging [1968] – A Brilliant, Provocative work of Anti-authoritarian

Oshima scrutinizes the stringent social and political frame of japan and the oppression of racial minority (Koreans). He puts an argument on how the law in itself might be responsible for oppression towards the minority, and perhaps the reason for the crime. Oshima ruthlessly attacks the rationale for capital punishment, questions the accountability of passing such judgement and discards the notion of nation, calling it an abstract idea.

Stream it on YouTube

The Death of Mr Lazarescu [2005, Cristi Puiu]

Can a person die only by murder or killing?

While we spoke about death by murder or state-sanctioned in the previous two films, Cristi Puiu’s morbid drama “The Death of Mr Lazarescu” deals with the death due to ignorance. The ignorance of the health system, in the hands of desensitised health workers. However, Puiu doesn’t judge the health workers. He doesn’t put the entire blame on them. Instead, he draws our attention to the mechanics of the crippled health-system and how rusty they have turned.

It’s an experiential and observational cinema at its best, lacking any dramatic moments. It comes without flab of heightened drama. The film operates on a very basic premise that can put you off as well – an old dying man tossed from one hospital to another for the stomachache treatment. Shot with the intention of capturing the nuanced details, and letting small bland moments to conjure up the necessary drama, it’s both sad and darkly funny. The old man gradually loses sight of his life as doctors and nurses lose their sight of him.

Stream it on YouTube

Japon [2002, Carlos Reygadas]

What you do when you are in conflict with life itself, and death’s the only answer?

How you survive when the will to survive is gone and life stops reciprocating. Carlos Reygadas’s debut feature film Japon deals with an artist, a painter, in conflict with an existential crisis, and on a mission to end his life. Love seems to have abandoned him. Life has turned dull. Has the city life beaten down him so hard? It’s a bleak tragedy lying in the middle of kindness, compassion and empathy. I say tragedy because what is life if you find no meaning in it. Its a cliche often pretentious people say to sound intellectual. However, once in a while, someone asks the same question with an eloquence that gives you a jolt, that stirs up altogether a different emotion, despite its obviousness.

There’s an ambiguity to his state when his journey starts. City dwellers may latch onto the thought that living in a city might have vacuumed everything inside him. Existential romanticisers might interpret differently. And some may spin it around sexual awakening. However, there’s no denying, he is on a voyage. A journey to finish something which has already ended for him. What rationale you give when something has lost a purpose? ‘lost’ is not a mere object but something profound and deep which society and individuals often fail to acknowledge.

So Long My Son [2019, Wang Xiaoshuai]

What happens when there’s a death in a family?

How does it change the course of someone’s life? Wang Xiaoshuai heart-breaking & piercing drama opens with a tragedy that defines the two neighbouring families against the changing face of modern China. One family coping with the loss of their only son and the other family carrying the terrible burden of guilt. As time decays, the emotional wound turns sore. When the guilt is unburdened, forgiveness becomes impossible.

So Long, My Son featured in our list of the 75 best films of the decade (2010s)

By the time we weep past the second act, the thick air of despondency and sadness fills you with insurmountable pain that won’t ease til the end. The seeping melancholia will consume you, wretch you, such is the film. Wang Xiaoshuai pulls this off without a hint of melodrama or contrived nature of storytelling. “So long, My Son” chronicles the biting journey of two families full of miseries & disappointments, from the period of adoption of one-child policy to the present day.

Landscape in the Mist [1988, Theo Angelopoulos]

What if the death is symbolical, the mere absence of a person?

Drenched in surreal imagery & evocative score, “Landscape in the Mist” is an allegorical journey of two kids in search of their long-gone father – through the mist, across the border, in the train, on the truck. It’s lyrical, like the other Theo Angelopoulos’s films, and the wind of melancholia is fierce than ever, and no doubt it’s bleak & heartbreaking too. However, the aching joy of the film lies in their bittersweet journey.

They meet strangers – drama troupe (like a subtle nod to the dramatic life itself), some treat them good, some are horrible. But Angelopoulos never uses their meeting with strangers to heighten the drama and derive the theatrics, unlike many other road-based films. He doesn’t even have to subvert the genre trope; It’s like life, inadvertently, every day passing uneventful, like the film itself.

Tokyo Twilight [1957, Yasujirō Ozu]

What if the absentee suddenly appears in your life?

Yasujiro Ozu’s ‘Tokyo Twilight’ is one of the least talked about masterpieces. This is probably among the best three works of Ozu. And a word of advice, watch this film once you have seen everything in Ozu’s filmography, as this film is quite different from his filmography though the soul stays the same. This is advertently quite a complex & psychologically hefty tragic-drama that questions the very ethos of Japanese traditional idea of a family and caustic influence of western-modernist ideology during the American occupation.

The Cranes Are Flying [Mikhail Kalatozov, 1957]

War casting a shadow on a young, beautiful relationship, ending in death – of the relationship and the person.

One of the most staggering masterpieces of post-Stalin cinema, Mikhail Kalatozov’s “The Cranes Are Flying” is as visually evocative as thematically dense. Kalatozov’s screenplay derives the strength and grittiness from the depiction of unheroic characters’ arc and their profound emotional nuances.

However, what proves potent here is the innovative scene compositions and hypnotic visuals that add to the tragic drama without overshadowing the emotional core of it. It renders a realism that is universal yet feel quite personal towards the end. Centred around an immensely passionate romance between patriotic Boris (Alexei Batalov) and Veronica (Tatiana Samoilova), their journey together is put on hold when Boris answers to call of duty on the border.

What follows is Veronica’s long wait for Boris to return while she had to go through several conflicting, sometimes distasteful, ordeals. Kalatozov does treat Veronica with sympathy but doesn’t make her a helpless woman begging for the audience’s sympathy. She is strong and could stand up for herself. Even when her choices are questionable and often leads to disappointment, she comes out strong in the end, quite hopeful too. She sees the world in a new light after experiencing the tragedy.

Maborosi [1995, Hirokazu Koreeda]

It’s a meditation on death and life and ways that loss alters us forever.

One of the best first works of a filmmaker that is as good as the most prominent works (Still Walking, Nobody Knows, Shoplifters) of him. Hirokazu Koreeda’s “Maborosi” masterfully weaves the visuals in the laconic narrative to build a fugue meditating on death, loss, mourning and loneliness. Ozu’s influence is omnipresent. The pillow shots and tatami shot fills the screen with an aching stillness.

All other Koreeda’s films are beautiful to look at, but the visuals are hardly imbibed in the narrative the way it does here. Be the spatial arrangement, minimalist production design or the direction of photography, they all succour to intensify the inward emotion our lead protagonist carries within. The procession scene followed by reconciliation or the scene where kids play near the lake, what masterful shots those are.

Climates [2006, Nuri Bilge Ceylan]

Some relationships turn shallow & empty due to dilapidation.

Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s mood piece on an existential relationship is an incredible, incredible piece of filmmaking. The rich visuals and soundscape encompass two individuals tied together in an elusive relationship, having difficulty communicating with each other.

Sansho the Bailiff [1954, Kenji Mizoguchi]

Without mercy, man is like a beast. Even if you are hard on yourself, be merciful to others. Men are created equal. Everyone is entitled to their happiness.

Kenji Mizoguchi’s “Sansho The Bailiff” is a profound reflection on humanity & mercy with an underlying piercing melancholy. It’s a surgical study of what social conscience does to society, and how intuitively oppressive body counters it with physical & psychological violence. Though there’s abundant melodrama, Mizoguchi doesn’t deceive his audience with a utopian victory of virtues, because when imperfect humans attempt perfectibility—personal, political, economic and social—they fail.

Kenji Mizoguchi’s melodrama – adapted from an epic folk tale and set in 11th-century feudal times – speaks to the modern world scarred by burgeoning capitalism and fascism. This is the world that rewards obedience and sycophancy in abundance. It has no place and respect for idealists and altruists, who are often silenced or rendered powerless. And there lies the reason for such an unusual choice of naming the film after its antagonist – Sansho, the bailiff. Read the complete review here.

Rocco and His Brothers [1960, Luchino Visconti]

Criterion Channel Writes – Looking for opportunity, five brothers move north with their mother to Milan. There, Simone and Rocco find fame, in the boxing ring, and love, in the same woman. Jealousy mounts, blood is shed, and a striving family faces self-destruction in this incisive, sensuous, emotionally bruising masterwork from director Luchino Visconti. With an operatic Nino Rota score and Giuseppe Rotunno’s glimmering, on-location cinematography, ROCCO AND HIS BROTHERS “represents the artistic apotheosis of Italian neorealism,” says A.O. Scott of the “New York Times.” Drawing from Dostoevsky and Thomas Mann, Visconti arranges his signature themes—modernity, class tension, familial discord—across an epic canvas that directly influenced later Italian-American sagas by Francis Ford Coppola and Martin Scorsese.

Last Year at Marienbad [1961, Alain Resnais]

One of the greatest mysteries of modern art – Love and this film.

“I get ideas and I want to put them on film because they thrill me. You may say that people look for meaning in everything, but they don’t. They’ve got life going on around them, but they don’t look for meaning there. They look for meaning when they go to a movie. I don’t know why people expect art to make sense when they accept the fact that life doesn’t make sense.” – David Lynch.

Welcome to the Marienbad, the luxurious purgatory, a ghastly place that might be someone’s forlorn memory, reminiscing a disappointing tryst without passion and lack of emotions. Or, it could be a reimagination of classical Orpheus and Eurydice, where Eurydice has lost her memory in the underworld and Orpheus help reconstructs everything with a bit of his imagination. Or, it could just be two people in love driving each other crazy. It’s more an experiential film with fractured narrative structure, reconstructing from the fragile memory whose pieces within one frame could contain a reality and fancy.

Another Round [2020, Thomas Vinterberg]

Another Round at life!

Arguably, one of the best films released in 2020. Mads Mikkelsen’s infectious energy ensures to end the terrible year on a better note. A life-affirming and a revitalising tale operating on an alcohol-based experiment to give life another round.

A washed-up school teacher Martin (Mad Mikkelsen), beaten to the dead-end, is on verge of slipping into midlife limbo. His marriage and job are on the brink of falling apart. Early on, in one of the most tragic scenes, handled with immense empathy and tenderness, Martin tears up in front of his three other friends during a birthday celebration. After this episode, four of them embark on a drinking quest, theorized by psychiatrist Finn Skårderud: that the body’s natural alcohol content is a couple of drinks too low. The quest brings joy again in their lives, and why shouldn’t it. They feel enliven. It breathes a new life into them.

Alcohol offers them ‘another round’ at life. However, the film draws a fine and responsible line to separate the drinking and abuse of it. There are repercussions when they tread a difficult part of putting it under control. Though the film sketches their rise from the ashes and eventual tragic downfall with broad brushstrokes, everyone’s incredible performances, especially Mads Mikkelsen, ensure the believability of everything happening to them. Mads Mikkelsen is an effortless actor. He can express and emote even with the slightest twitch in his eyes, and that’s one of the reasons we feel shaken when he tears up, though we hardly know the character.

Thomas Vinterberg celebrates the culture of alcohol without romanticising it and without any moralistic provocation. Druk is an incredible, incredible film. A tragic comedy that drinks in 1% alcohol and offers abatement for such a horrible year. It offers the best climax scenes for all the films released in 2020.

Other strong recommendations;

Mysteries of Lisbon [2010, Raúl Ruiz]

Museum Hours [2012, Jem Cohen]

Das boot [1981, Wolfgang Petersen]

A Brighter Summer Day [Edward Yang, 1991]

Jeanne Dielman, 23, Quai du Commerce 1080 Bruxelles [Chantal Akerman,1975]

The Disciple [2020, Chaitanya Tamhane]

Dead Man’s Letters [1986, Konstantin Lopushansky]

Fantastic Planet [1973, René Laloux]

Vagabond [1985, Agnes Varda]

An Autumn Afternoon [1962, Yasujirō Ozu]

The final film of the master Ozu, the end of the genre itself and the end of the list.

Swan song of Ozu comes from a very personal space, like his other films, but this time around, the bittersweet taste of filial relationship, their dependency, their dreams and hopes hit quite close to home. Chishū Ryū’s widow character Shūhei Hirayama feels like an incarnation of Ozu. His melancholic feeling of loneliness in immediate future after his daughter gets married off, really makes you quiver in horror. You could feel in it in your bones how Ozu must have felt staying single all his life.

![Three Sisters [2012, Wang Bing]](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Three-Sisters-1024x576.jpg)

![A Moment of Innocence [1996, Mohsen Makhmalbaf]](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/A-Moment-of-Innocence.jpg)

![The Best of Youth [Marco Tullio Giordana, 2003]](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/The-Best-of-Youth-Marco-Tullio-Giordana-2003-1024x576.jpg)

![Z [Costa-Gavras, 1969]](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Z-Costa-Gavras-1969-1024x576.jpeg)

![Napoleon [1927, Abel Gance] - films watched in 2020](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Napoleon-1927-Abel-Gance-1024x576.jpg)

![Tokyo Twilight [1957, Yasujirō Ozu]](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Tokyo-Twilight-1957-Yasujiro-Ozu-1024x576.jpg)

![Rocco and His Brothers [1960, Luchino Visconti]](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Rocco-and-His-Brothers-1960-Luchino-Visconti-1024x626.jpg)

![Another Round [2020, Thomas Vinterberg] Arguably the Best film](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Another-Round-2020-Thomas-Vinterberg-1024x420.jpg)

![Another Round [2020] Review – When Honesty Overcomes Moralism](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Another-Round-highonfilms-1-768x432.jpg)