Introduction to The Adult Animated Comedies of the ‘70s and ‘80s: It’s safe to say that a hefty amount of cartoons nowadays (whether they be films, TV shows, or internet videos) are produced and targeted with adults as their primary audience. With each generation of folks being brought up with more and more exposure to cartoons, it seems many adults now are less and less inclined to think of cartoons as just being for kids (a similar attitude has been brought upon video games). With the likes of South Park and Family Guy bringing adult humour in cartoons to a mainstream fore, followed up by the vast array of adult cartoon comedy shows of Comedy Central to Adult Swim to Netflix, it appears cartoons for adults has been the norm since around the late ‘90s.

But there has been a time before that, several decades earlier, when adult cartoon comedies were first making their venture into the cinema. We have Ralph Bakshi to mostly thank for that, the filmmaker who spent most of the ‘60s working as a director on a number of childhood favourites (depending on how old you are), most notably Spider-man. He also put out a number of animated shorts that flexed his creative muscles and was soon given the helm of adapting Robert Crumb’s comic strip Fritz the Cat into a feature animated film (despite Crumb’s extreme hesitance and lack of support). Fritz the Cat, the first X rated animated feature to be released in America, became a box-office hit and kickstarted this new short-lived, but most influential trend.

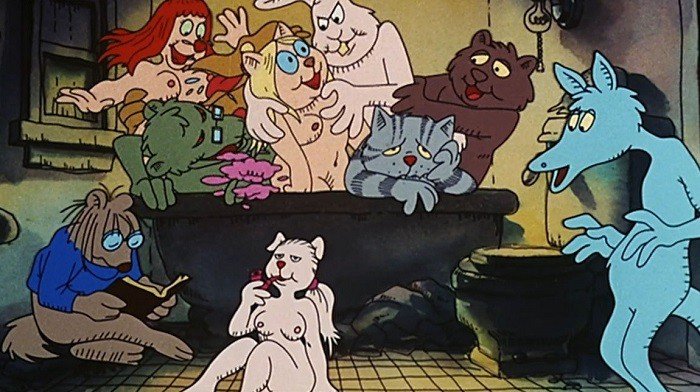

Like many of the films that will be discussed here, Fritz the Cat is soaked in its own time and culture. Depending on who you ask, it’s either outdated or dated – some may see the film’s style and cultural mise en scene as too removed from our current culture, or they could see the film as a time capsule of some sort of cartoonish and embellished representation of the counter culture period. What is identifiable in the first half of the film is the surface level material that is the main selling point such as the animated drug-taking and love-making. What is identifiable in the second half of the film is a more blunt criticism of the fringe culture of American cities such as New York, specifically the biker gangs who are shown in this film to have violent disregard towards most people, specifically women. There’s a level of poignancy on a cultural level, though is conveyed through the film in a personal matter, and this sort of surprising insight of these sorts of films is yet to reach its greatest heights. On a more technical level, the film is notable for its astounding animation – like all other films of this film movement, it’s crude and completely produced by a very small team of animators (and in a short amount of time), but like certain other films of this movement, it makes up for its limited animated range with its creativity and invention that goes to serve in this film the proudly hyperbolic perspective of this kind of New York City living.

With the success of Fritz the Cat, the most profitable independent animated feature at the time, Bakshi was then given free rein to produce the film he originally wanted to debut with – Heavy Traffic. Released in 1973, Bakshi’s second film is similar in tone and style to Fritz the Cat, but features mostly human characters, not fun anthropomorphic creatures. Being Bakshi’s most personal and introspective film, this is his magnum opus and the pinnacle of this movement. Amidst the laughs and poignancy, Heavy Traffic has one of the most illustrative, most underseen portrayals of the dirty, gritty, yet still liveable New York City of the ‘70s, a time when films delved into the more squalid nature of their times. The audacious mix of animation that features cartoons, real-life, photographs, stock footage, and rotoscoping, along with the sometimes very colloquial dialogue that sounds like eavesdropping on any old conversation, works entirely to enhance this film’s incredible portrayal of the big city during this big time.

He followed it up two years later with Coonskin, a film as racially charged as its title suggests. Although the storyline is too much for Bakshi to handle and the mix of live-action and animation isn’t quite as adventurous and as creative as in Heavy Traffic, Coonskin was still a punch in the mouth kind of film for mid-‘70s America to chew on. It didn’t go well for everyone, as Al Sharpton and the Congress Of Racial Equality protested the film for its racist content (despite not having seen the film since the protests erupted before the film’s release), and one such screening of the film was met with smoke-bomb protests from the organisation. Bakshi hired many black animators to work on the film, in a time when black people of such profession generally weren’t employed, so Al Sharpton and co seemed to be barking up the wrong tree. They perhaps could accuse the film of racism towards Jews, in the way it conveys how non-black races like Jews have corrupted and manipulated the culture of the blacks (best exemplified in the film’s final shot), but Coonskin is, deviously, a sympathetic portrayal of African-American culture in the ‘70s, showing their strength and unity amidst either oppression and the aforementioned cultural shifting. After this unfortunately successful boycott, Bakshi did not tackle this kind of animated crassness again until 1982 with Hey Good Lookin’, which put the crassness in the 1950’s time setting, but still within the grittier areas of New York (specifically Brooklyn).

Just like Crumb was dissatisfied with Fritz the Cat, Bakshi was equally so with the sequel to his own film, though it is debatably superior. The Nine Lives of Fritz the Cat was released in 1974, directed by Robert Taylor, and was made to capitalise on the success of the first movie, but lightning did not strike twice in regards to critical and general acclaim. Though this sequel is very much based in its episodic form, as the title suggests (nine segments depicting a life of Fritz), this loose narrative structure makes this film’s scope even more encompassing and malleable than its predecessor. The lives of Fritz involve him not just in early ‘70s New York, but in ‘40s Germany working alongside Hitler and in the early ‘30s as a fat-cat suffering an economic collapse (brilliantly conveyed in a kaleidoscopic, psychedelic song montage that is one of the most artful depictions of greedy downfall shown in a film). What ties this vignettes together is that they are all apparently fantasies of a stoned Fritz as he lounges on the couch while his old lady berates him (deservedly so) over his lazy lifestyle, this framing narrative offering a cool, collected, yet sympathetically felt portrayal of a deadbeat, especially when Fritz concludes “this is about the worst life I’ve ever had”. Robert Taylor shows he has an even varied scope of time settings than Bakshi did and it’s unfortunate that he had a limited career and never got to work on another film like this ever again.

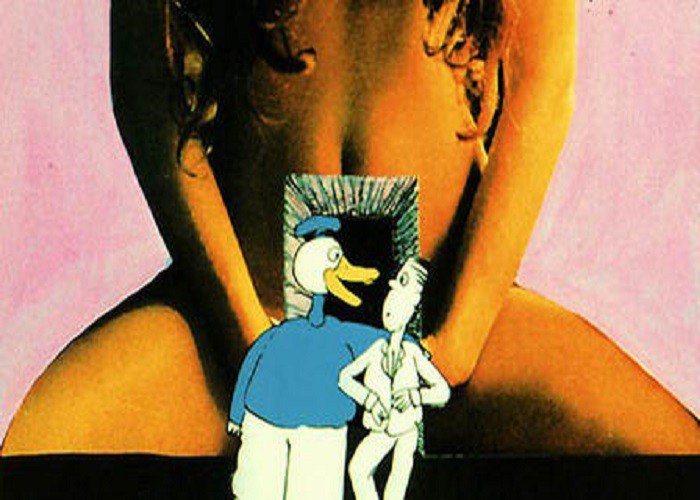

Another film released in 1974 that capitalised on the success of Fritz the Cat was Down and Dirty Duck, another film that featured anthropomorphic characters, though alongside human characters. Produced by the uncredited king of trash Roger Corman, the film’s original title would have played out as ‘Roger Corman’s Cheap!’ and he requested its change. With a lower budget than Fritz the Cat (and it shows), the beginning of the film starts off very mildly, in terms of animation and comedic tone, as its crude black and white minimalism serves as a reflection of the mundane life of the main character. In contrast, the cool and groovy Dirty Duck injects the film with colour, real-life imagery, and a more impactful comedy presence. If you withstand the quaintly amusing first half, you’ll be rewarded with a more psychedelic, more surrealistically played-out, and more bizarrely laugh-out-loud second half. It doesn’t have quite the amount of social representation and critique as in the two Fritz the Cat movies, but once it gets to the lengthy highway scene, cultural satire is portrayed through a series of characters who make up each brief vignette. The film still contains a high amount of fascination with degradation and squalidity, a unique characteristic of Western-culture films from the ‘70s.

Several inspired animators from outside of America tried to replicate this fame (or infamy), which resulted in 1973’s King Dick from Italy and 1979’s Historias de amor y massacre from Spain. And there was France’s Picha, who became second to Bakshi as one of the forefathers of adult cartoon comedy, even though he only made three of such films throughout the ‘70s and ‘80s. His first, 1975’s Tarzoon: Shame of the Jungle, was something of an adult version of Tarzan (though not legally speaking) and it proved to the world Picha had a far more perverted and sexually warped mind than even Bakshi did and wanted the world to see it. The level of imaginative vulgarity on screen is admittedly impressive – enemies that resemble male genitals bounce around and fire white projectiles at their enemies, which sounds like something a crass teenage boy would come up with, though the scene that reveals exactly how these male genital enemies are created in a factory is astonishing in its utter crassness. Lewd animated gags are aplenty, though the other half of the humour actually comes from lengthy pieces of colloquial dialogue that build comedy in the words that is (at least in the American dub) rather amusingly written and acted.

His 1987 film, The Big Bang (or as known by its original French title, Le Big Bang), was a last hurrah for this film movement, exuding the same amount of low-brow crude creativity in its fantastical setting mixed with sexual and scatological imagery – another classic staple of this movement. Apart from the change of fantasy setting from the jungle of the primitive to the sci-fi of the future, there isn’t much of a difference between these two films of Picha, though they work as excellent counterparts that both exemplify his wild contribution to this movement.

Out of the small amount of these adult cartoon comedies, not all were masterpieces and some were barely even watchable. Released between Picha’s excellent Tarzoon and The Big Bang, his attempt at stereoscopic animation with BC Rock sounded appealing to its intended target audience – a raunchy, explicit, and historically silly caveman cartoon with a rock ‘n’ roll soundtrack – but the film was an abysmal mess, with the vague and lazy animation barely making any geometric sense. The English-language dub was provided by the Funny Bros (who must use the word Funny sarcastically) and they just sound like two eleven year olds frantically trying to improvise all the dialogue with no regard for lip-syncing or being funny. I can’t imagine the original French dub being any sort of improvement, this film just comes across as a thoroughly lacklustre and barely pulled-together production. Along with the aforementioned dreary Historias de amor y massacre, these two films work on little to no dialogue, sparse and erratic sound design, incomprehensible animation, which overall makes them the polar opposite to Heavy Traffic in regards of quality.

There was nothing like these films to come out until the movie adaptations of Beavis and Butt-head and South Park were released in the late ‘90s, and although Picha returned in 2007 with Snow White: The Sequel and Bakshi made a return in 2015 with his short Last Days of Coney Island, this movement is making an inch of a return with dangers of not fully re-establishing itself. Later this year, the R-rated animated comedy Sausage Fest will very likely be what we can expect from a Seth Rogen film these days, but for someone who is a big a fan of these particular adult cartoon comedies of the ‘70s and ‘80s, I find it highly unlikely that films so in tune with that particular culture of the time can ever be resurrected – feature films like that would not survive in this current film climate, and are best suited to the Flash animated shorts currently championed by Michael Cusack, Psychic Pebbles, and others from YouTube and Newgrounds who are using their own style to continue keeping the spirit of lude, crewd, and rude animated goodiness alive. As much of a pleasure it would be to see a resurgence in animated films of the specific kind of humour and cultural satire of this movement, especially in such a changed Western culture, it seems this brief and neglected, yet influential movement was just a one-off for its specific time and place.

![Free Fire [2017]: Insults & Infections](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/free-fire-768x511.jpg)

Great article. As an artist, this kind of animation and content are truly missed in 2017.

Inspiring.