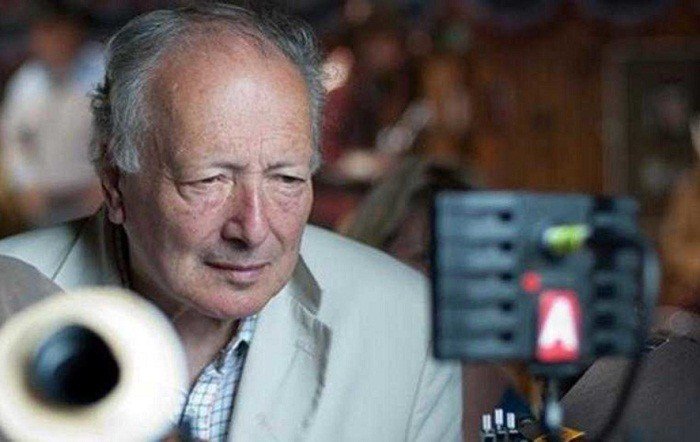

During the first week of July 2016, the world of cinema lost perhaps two of its most unheralded and underappreciated filmmakers. On July 1, Robin Hardy passed away at the age of 86. The next day, Michael Cimino was found dead in his home at the age of 77. The purpose of this article is to examine the careers of both filmmakers and shed some light on some of the interesting parallels shared by two of their most famous (or infamous) films.

Robin Hardy was a novelist and short story writer before starting his career as a film director. He acquired his first feature film directing job, The Wicker Man, through an acquaintance of his fellow writer Anthony Shaffer, who wrote the screenplay that the film is based on. The film, which told the story of a conservative police sergeant summoned to investigate the reported disappearance of a young girl on a small, secluded island off the coast of Scotland only to clash with the island’s eccentric and heathenistic locals, was shot entirely on location in and around Newton Stewart, Scotland in the Fall of 1972. While prepping the film for a 1973 theatrical release date, Hardy cut a 99-minute version of the film, now called “The Long Version.” Shortly after, the film’s distributor, British Lion, ran into financial difficulty and was taken over by EMI. New bosses were appointed, and neither was particularly keen on the project they had inherited. As a result, the film was unceremoniously released as a “B -picture” part of a double bill with Nicholas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now. Not a bad double feature if you ask me.

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, the film was sold to B-movie kingpin Roger Corman, who re-edited the film into a shorter 87-minute version, now cleverly known as “The Short Version,” suitable for American drive-in audiences. It would take years before the film would become the internationally renowned cult classic it is today. Beginning in 1976, Hardy sought to restore the film to its original vision. The result was a 95-minute film cut now known as “The Middle Version.” This version of the film was re-released theatrically at the end of the 70s to generally favorable responses, and the film has not looked back ever since. Revival screenings such as the one hosted by famed British cult filmmaker Alex Cox in 1988 only helped boost the film’s prestige, and it’s now considered one of the finest-ever examples of British cinema. It’s also become a massive influence on future generations of filmmakers like Edgar Wright and Ben Wheatley.

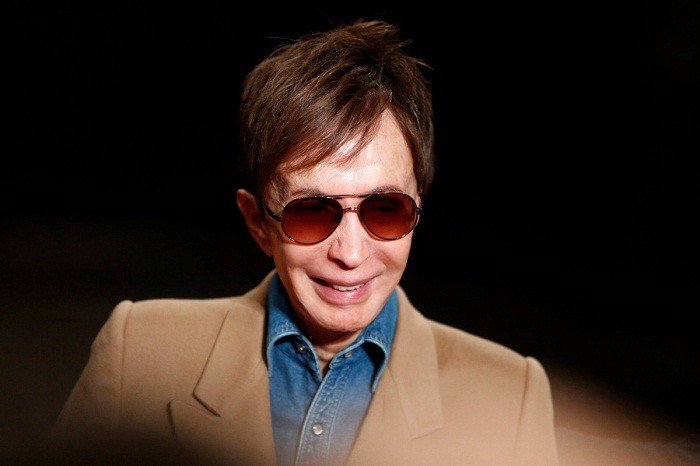

In the years that followed The Wicker Man’s initially tepid response, Robin Hardy apparently had considerable difficulty finding other directorial work, as it would eventually take 13 years before his follow-up film, “The Fantasist,” finally saw the light of day in 1986. Hardy’s IMDP page only lists two other credits to his name since then, a screenwriting credit for “Forbidden Sun (1989)” and a directorial credit for “The Wicker Tree (2011)”, a spiritual successor to The Wicker Man that Hardy also wrote originally intending it to be the middle part of a trilogy of films with the third part now implausible ever to see the light of day.

When revisiting his most famous film nowadays, you’ll probably notice that it hasn’t aged very well. It’s got a decidedly early 70s flavor attached to it, and modern audiences may be repelled by the film’s gingerly pace and somewhat bizarre tone and imagery. However, there’s still more than enough there to make one understand why it’s grown such a large cult following over the years. The film’s picturesque locale, mixed with the idiosyncrasies of its characters, as well as the overwhelmingly uneasy sensation you acquire while watching it, are a winning combination. The same can be said of the cultural and religious clashes at the film’s center.

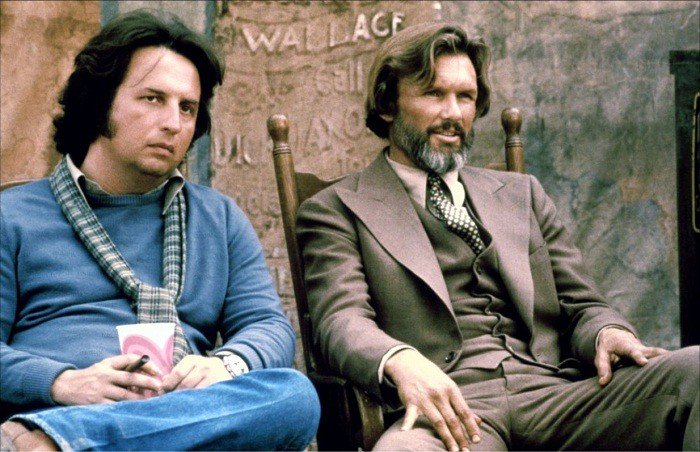

Much like Don Draper, Michael Cimino launched his career working in the advertising business in New York City during the 1960s. He made a name for himself by directing meticulously crafted commercials for major conglomerates such as Kodak and United Airlines. Cimino eventually moved from Madison Avenue to Hollywood in the early 1970s, where he found initial success as the co-screenwriter of films such as “Silent Running (1972)” and “Magnum Force (1973)”. It’s while on the set of the latter film, Cimino met the man whom he’s given full credit for having helped launch his career, Clint Eastwood. Eastwood gave Cimino his first feature film directing job with Thunderbolt and Lightfoot, based on Cimino’s screenplay. Upon its release in 1974, the film became a hit with critics and audiences alike, even earning actor Jeff Bridges an Academy Award nomination for his performance. 4 years later, Cimino made the film that is universally regarded as his finest achievement, “The Deer Hunter (1978)”. Upon its release in 1978, the film became a smash hit, easily eclipsing the success of Thunderbolt and Lightfoot, and was one of, if not the, most highly regarded films of that year. Its estimation has only grown over the years. The film was awarded 5 Academy Awards for his efforts, including Best Picture and Best Director. Suddenly, Cimino became the toast of the town in Hollywood and was quickly fielding offers from various movie studios hungry for a follow up. One movie studio in particular was desperate for a hit. Despite scoring a trifecta of Best Picture winners in their own right with One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), Rocky (1976), and Annie Hall (1977), United Artists was in turmoil after an internal conflict with parent corporation Transamerica lead to the high profile departures of 3 powerful executives, Arthur Krim, , Eric Pleskow, and Robert Benjamin in 1978. The 3 men left to form Orion Pictures, leaving United Artists behind holding the bag. As a result, inexperienced or ill-suited executives were tasked to fill the void, some of whom were anxious to work with the man who just took home the Oscar for Best Director. Before long, Cimino was greenlit a budget of $7 million to go out on location in Montana to make a film originally titled The Johnson County War.

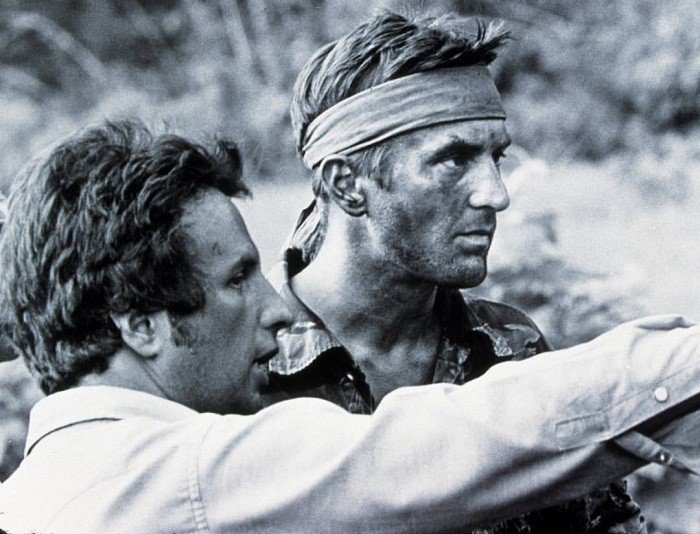

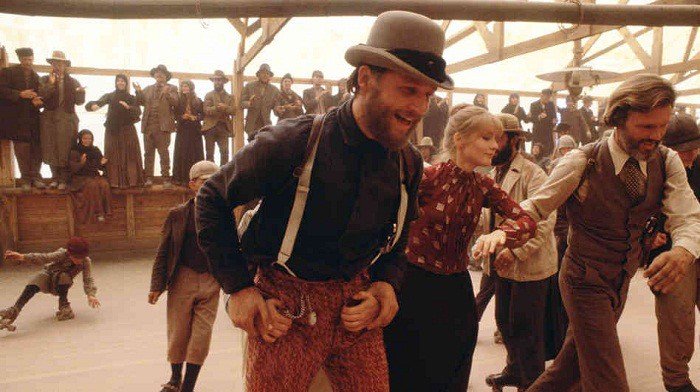

In the spring of 1979, mere weeks after picking up his Oscar and still filled to the brim with piss and vinegar and striving to achieve the utmost cinematic perfection for his follow-up, Cimino commenced shooting on the film that would eventually come to signal his own downfall, Heaven’s Gate. The film was meant to be an epic from day one, a grand scale Western about the real life Johnson County War, where, in the early 1890s, the American government sanctioned wide scale killings of European immigrants at the behest of local ranchers and settlers. Almost immediately, problems began to arise on set as Cimino’s meticulousness and obsessive attention to detail started causing delays and budget overruns. It’s been said that a mere 6 days into filming the film was already 5 days behind schedule and a grand total of 90 seconds of usable footage had been shot, akin to $1 million per usable minute. Shortly after that, the film’s budget ballooned to $12 million. It got to a point where certain scenes were taking between 50 or 60 takes to complete and there was nobody on set capable of reigning in the director. The film’s enormous scale coupled with Cimino’s rampant perfectionism proved to be a lethal combination for all parties involved including United Artists who were quickly beginning to regret the level of autonomy that they had granted to the filmmaker. Negative publicity began to plague the film once word got out of its various delays, budget overruns and the supposedly tyrannical nature of the director at the helm. It was now too late, United Artists had simply invested too much into the film to pull the plug and as a result, the film’s budget increased to $18 million. Cimino however, remained undaunted as he was still determined to achieve his artistic vision. He simply didn’t care about how much money the film cost, all he cared about was making the best film he could make and in order for that to happen he needed to make it as authentic to the period as possible. Filming finally wrapped in September 1979, 5 months after it began. By then, Cimino had shot a record 1.3 million feet of film and spent in excess of 100% of his initial approved budget.

The worst was far from over however, as now Cimino was faced with the daunting task of going through over 200 hours of raw footage in order to cut it down to a feature film length no longer than 3 hours. Cimino and his editor worked around the clock scrambling to meet United Artist’s deadline for a Christmas 1980 release date. After 8 months of furious editing, Cimino had pieced together a rough cut 5 and a half hours long and screened it to United Artist execs that June. By mid-October, Cimino had managed to cut the footage down to a far more manageable, albeit still excessive, 3 and a half hours long. It would be this cut of the film that would be screened to critics in New York during the film’s November 1980 premiere date. Never before in the history of Hollywood has a single screening been more damaging to a film’s reputation. Vincent Canby, the chief film critic for the New York Times, Infamously wrote of the film “it fails so completely that you might suspect Mr. Cimino sold his soul to obtain the success of The Deer Hunter and the Devil has just come around to collect.”, thereby sealing the film’s faith. Shortly thereafter, United Artists pulled the film from its scheduled theatrical release in order to provide time for Cimino to cut the film down even more, a decision that only served to fuel its now overwhelmingly negative publicity. When the film’s new 149 minute cut finally saw a theatrical release in April, 1981, it was all but over, the film only managed to pull in a paltry $1.3 million at the box office, well bellow its catastrophic $44 million budget. Keeping in mind that while $44 million doesn’t seem all that irregular in today’s day and age where movie budgets reach in excess of $200 million or more, back in 1981, Heaven’s Gate was one of the most expensive film’s ever made.

The diminishing returns proved to be too much for even the once powerful United Artists to handle as parent corporation Transamerica sold what was left of the company to MGM that same year. The brunt of the blame for the demise of United Artists was placed on the failure of Heaven’s Gate. With the benefit of hindsight, the film, along with other big budget flops like 1941 and One From the Heart, has also been blamed for the demise of the director driven “New Hollywood” era that began in the late 1960s. Cimino went from being the king of Hollywood to persona non grata within the span of 2 years. It would take nearly 5 years before he was entrusted to helm another big budget feature film. His next film, Year of the Dragon starring Mickey Rourke came out in the summer of 1985 to a mixed critical reception and somewhat disappointing box office results. Cimino would only go on to direct 3 more films, The Sicilian (1987), Desperate Hours (1990), and Sunshaser (1996), none of which proved to be successful before finally going into a period of semi-retirement.

Over 30 years after Vincent Canby’s scathing review essentially sealed Heaven’s Gate’s faith, the film got a new lease on life when it was re-released in an altered 216 minute director’s cut during a revival screening at the 2012 Venice International Film Festival. The film was met with a rapturous response concluding in a standing ovation from those in attendance. Even the New York Times, Canby’s old stomping ground, exercised past demons by declaring that “Time Has Been Kind to ‘Heaven’s Gate’” in their review of the revival screening. The 216 minute version would eventually find its way to DVD and Blu-Ray later that same year, released by the prestigious Criterion Collection. It’s through the Criterion Blu-Ray that I myself first discovered the film a few years ago and I was floored by how just how good the film really was. Besides the fact that its length is undeniably excessive, it’s still a powerfully rewarding movie experience. It’s the kind of old fashioned and lavishly constructed epic that Hollywood just doesn’t make anymore and it’s worth watching merely for the sheer visual panache brought forth by its highly skilled cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond (who, coincidentally also recently passed on January 1) working at the very top of his game. Kris Kristofferson, Jeff Bridges, Isabelle Huppert and Christopher Walken also deliver fine performances in the lead roles. What’s even more remarkable is the film’s look into the horrifying violence that can manifest itself from human rights violating anti-immigration laws is as prescient today as it was the day the film was released. If you’ve never seen it before or have been turned off at all by the decades of bad press, do yourself a favor and pick up a copy, you’ll be happy you did.