The rape-revenge genre in cinema holds a paradoxical landscape within the cinematic language, provoking discomfiting thoughts, heated discussions, and a raw and visceral emotional response in the audience. Inherently feminist in outlook, this genre has often been revered as the expression of feminist rage and fury. However, this controversial and notorious subgenre of horror has been reviled as exploitative, with accusations of voyeurism and complacency.

Caught in a tug-of-war between being celebrated and dismissed, these films offer a rare dichotomy of trauma and catharsis, and justice and spectacle. This motif has made its presence in arthouse classics as well as in the excesses of grindhouse cinema and has evolved, unfolding across shadowy city alleys, sun-scorched rural backdrops, tense courtrooms, and surreal, neon-lit dreamscapes.

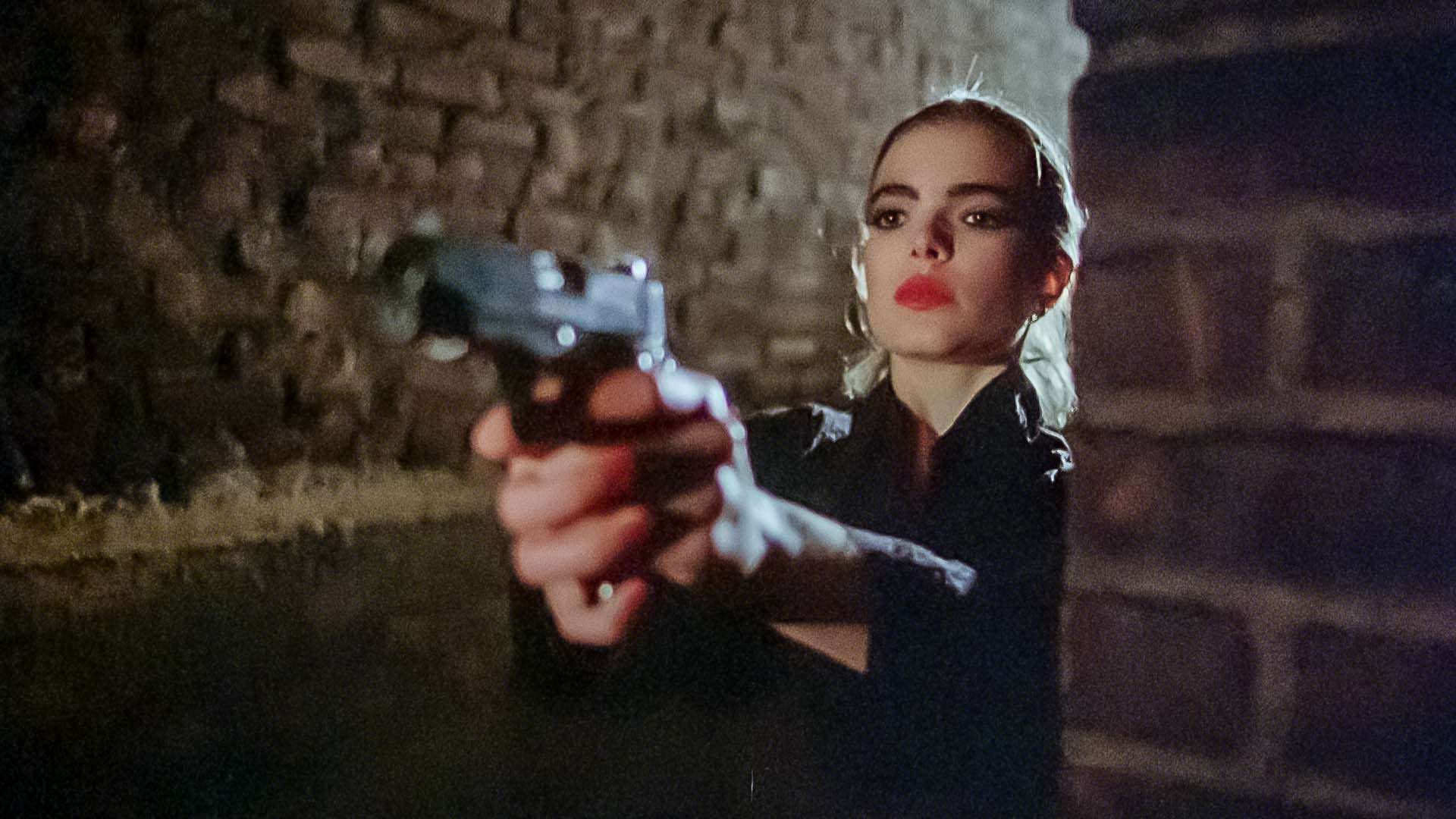

The genre comprises two major plot points: the sexually abused survivor (usually female) and retributive violence. The story follows a familiar trajectory – a woman is raped, brutally, often graphically – then left for dead or shattered. But she survives. She transforms. And then, she kills. What follows is a spree of vengeance, often mirroring the violence done to her, and occasionally eclipsing it.

These films ask hard questions with few clear answers: What does justice look like when the system fails? Can revenge restore dignity? Fundamentally, the genre serves twin functions: it dramatizes sexual violence while also purporting to avenge or redress it. This duality makes rape-revenge films uniquely fraught, both ethically and aesthetically. The rape scene, showcased in graphic and explicit detail, with gratuitous and needless violence, reinforces the voyeuristic tendencies and gendered objectification such films strive to critique.

On the contrary, the revenge sequence is often portrayed in a stylized, cathartic, and even pleasurable manner, where the audience is encouraged to align with the avenger, and this cinematic violence implies a mode of symbolic justice.

Rape-revenge cinema has broader social and political implications on gender, justice, and bodily autonomy. These discourses reflect the failure of legal institutions to protect survivors, the normalization of rape culture, and the radical potential and limits of female rage. Its endurance and evolution across decades suggest that it functions not merely as exploitation, but as a contested cultural form through which shifting notions of victimhood, agency, and resistance are articulated and challenged.

The genre has evolved in form and ideology, from the tormented spiritualism of “The Virgin Spring” (1960) to the blood-splattered nihilism of “I Spit on Your Grave” (1978), the psychosexual anarchy of “Baise-moi” (2000), and the subversive playfulness of “Promising Young Woman” (2020). With every era, the rape-revenge narrative reinvents itself, reflecting shifting anxieties around gender and power.

In this essay, I aim to trace the history and transformation of the rape-revenge film, analyzing its aesthetic choices, political implications, and cultural significance, especially within American and European cinema. Drawing on key examples from canonical and controversial works, it examines how the genre negotiates the representation of trauma, the aesthetics of violence, and the ethics of retribution.

The Historical Arc of Rape-Revenge Cinema

Roots of Rape-Revenge Motif in Pre-Code Era (1929-1934)

The “woman-in-peril” trope was a staple across many genres during the classical Hollywood era, often positioning female characters as passive victims of violence or sexual threats. Yet, even within these restrictive frameworks, narratives occasionally emerged in which women resisted, retaliated, or sought justice, laying early groundwork for what would later crystallize as the rape-revenge genre. These proto-revenge narratives can be traced as far back as the Pre-Code era (1929–1934), a brief but transgressive period before the enforcement of the Hays Code imposed stricter moral censorship on American cinema.

Alfred Hitchcock’s “Blackmail” (1929), his first sound film, is one of the earliest cinematic depictions of a woman fighting back. The protagonist, Alice White, stabs a man in self-defense after he attempts to sexually assault her. The narrative is further complicated by the moral dilemma faced by her detective boyfriend, who uncovers her culpability yet seeks to protect her. Similarly, Stephen Hopkins’ “The Story of Temple Drake” (1933), based on William Faulkner’s controversial novel Sanctuary, implies the rape of its female protagonist through visual ellipses and tonal shifts.

Miriam Hopkins’s performance as Temple signals a disruption of the passive-victim archetype, challenging contemporary sensibilities. In “Shanghai Express” (1932), directed by Josef von Sternberg, themes of racialized sexual violence and female vengeance intersect. Anna May Wong’s character exacts fatal revenge on her rapist, asserting a rare form of narrative justice in a period when such agency was seldom granted to women, especially women of colour.

Likewise, “Wild Boys of the Road” (1933), a Depression-era social drama, includes a subplot in which a girl is assaulted by a train conductor. Her male companions respond by violently avenging the act, offering an early cinematic expression of collective retribution.

Monstrous Desires and Sexual Threat in Early Horror Cinema (1930s-1950s)

As the Pre-Code era came to a close, the horror genre began to emerge as a powerful and disturbing space for exploring anxieties surrounding sexuality, violence, and the female body. The early 1930s witnessed the consolidation of monster-centred films such as “Dracula” (1931), “Frankenstein” (1931), “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde” (1931), “Murders in the Rue Morgue” (1932), “King Kong” (1933), “The Mummy” (1932), “The Island of Lost Souls” (1932), and “Freaks” (1932).

While explicit depictions of sexual violence were constrained by censorship, these films frequently implied rape or sexual domination through monstrous metaphors. The eroticized violence toward white womanhood is echoed in “King Kong” (1933) and “The Island of Lost Souls” (1932), where bestiality and hybridization loom beneath the surface of the plot. Similarly, the visual design of Hyde in Mamoulian’s “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde” (1931) also suggests primal, racialized caricatures that position Hyde as both animalistic and sexually predatory.

Though the introduction of the Hays Code in 1934 dampened the overt eroticism and violence of early horror films, the genre’s fixation on sexualized threats persisted. By the 1940s, horror leaned toward camp and melodrama, as seen in films like “Son of Dracula” (Robert Siodmak, 1943) and “Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man” (Roy William Neill, 1943).

Yet beneath their often absurd premises, the latent themes of sexual violation and patriarchal fear remained intact. These anxieties would later resurface with renewed force in the mid-to-late 1950s when the weakening of the Code allowed filmmakers to probe deeper into the horror of the violated body, setting the stage for the explosive rape-revenge films of the 1970s.

Related to Gender and Violence in Film: 30 Best Feminist Horror Movies of All Time

Foundations of the Rape-Revenge Cinema (1960s – early 1970s)

The rape-revenge motif in cinema finds its early expressions in European arthouse cinema. In 1960, the term “rape and revenge” was coined in Ingmar Bergman’s “The Virgin Spring,” considered the earliest film and precursor of the subgenre. Set in medieval Sweden, the film tells the story of a devout Christian father Töre (Max von Sydow) who exacts revenge on three herdsmen who raped and murdered his daughter, Karin (Birgitta Pettersson). He bludgeons the men to death in a moment of cold, ritualistic fury.

The film explores themes of divine justice and moral reckoning, positioning the act of revenge as a spiritual crisis. It also establishes a structural motif: rape as inciting incident, followed by male-driven retribution. The victim herself remains silent, absent, or symbolically inert. The rape itself is implied rather than explicitly depicted, characteristic of the era’s reluctance to portray sexual violence onscreen.

Wes Craven’s “The Last House on the Left” (1972), a loose remake of “The Virgin Spring,” brought the motif into American exploitation cinema. Unlike its predecessor, Craven’s film was far more graphic, both in its depiction of rape and violence. The rape and murder of teenager Mari Collingwood (Sandra Cassel) is depicted in prolonged detail, pushing the boundaries of what could be shown on screen. Her parents, upon discovering the perpetrators, exact sadistic revenge. It marked a shift from metaphysical concerns to visceral, bodily horror, foregrounding the brutality of both victimization and revenge.

Craven’s film rejects the spiritual reckoning of Bergman’s, instead offering a grim, chaotic descent into eye-for-an-eye brutality, blurring the lines between victim, avenger, and aggressor. In these films, rape was a tool for male character development or patriarchal honour more than a narrative space for the victim’s subjectivity.

The Exploitation Boom: Voyeurism and Violent Liberation (1970s–1980s)

The 1970s witnessed a surge of rape-revenge films, particularly in American exploitation and grindhouse cinema. This period was marked by a collision of rising feminist discourse, post-1960s sexual liberalism, and a cinematic market eager to push the boundaries of onscreen violence and sexuality.

The decade saw a wave of exploitation films that centred on the female victim-turned-avenger. Films like “I Spit on Your Grave” (1978), “Thriller: A Cruel Picture” (1973) and “Ms. 45” (1981) drew both notoriety and condemnation for their graphic depictions of rape and their often gleeful portrayals of revenge. These works presented female victims exacting bloody vengeance on their attackers – castrating, shooting, mutilating – but also revelled in prolonged scenes of sexual violence, often shot with a voyeuristic gaze.

Meir Zarchi’s “I Spit on Your Grave” (1978) established the genre’s now-classic tripartite structure: rape, transformation, and revenge. The film follows Jennifer Hills (Camille Keaton), a writer who is gang-raped and left for dead by four men. After a period of recovery, which includes not only physical recovery but also a psychological shift, wherein the victim gains agency by embracing violence, she meticulously hunts down and murders each of her assailants.

Its 30-minute rape sequence has been widely condemned for its voyeurism, while the revenge has been interpreted alternately as feminist catharsis and sadistic fantasy. Critics lambasted the film for its gratuitous violence and perceived misogyny, while some feminists, such as Camille Paglia, saw in it a form of radical empowerment.

While the film was critiqued for its aggressively exploitative nature and seen by some as a crude response to misogyny, it nonetheless possesses an undeniable, if unsettling, power. Carol J. Clover, in the third chapter of her 1992 book Men, Women, and Chainsaws, noted that she and others like her “appreciate, however grudgingly, the way in which [the movie’s] brutal simplicity exposes a mainspring of popular culture.”

She also argued that the film’s sympathies are entirely with Jennifer, that the male audience is meant to identify with her and not with the attackers, and that the point of the film is a masochistic identification with pain used to justify the bloody catharsis of revenge.

Bo Arne Vibenius’ “Thriller: A Cruel Picture” (also known as They Call Her One Eye) offers a similar arc but stylizes the revenge through the lens of exploitation chic – slow-motion shootouts, eye mutilation, and sexual slavery – turning trauma into operatic excess.

The film follows a mute young woman named Madeleine/Frigga (Christina Lindberg), who is abducted, sexually exploited, and addicted to heroin by a sadistic pimp. After enduring prolonged abuse, she embarks on a meticulously planned campaign of vengeance, training in martial arts, firearms, and combat driving. Thriller has attained cult status and is frequently acknowledged as a precursor to later female avenger narratives, most notably Quentin Tarantino’s “Kill Bill.”

Abel Ferrara’s “Ms. 45” (1981), in contrast, introduces a more psychologically complex protagonist: a mute seamstress Thana (Zoë Tamerlis) who, after being raped twice in one day, embarks on a killing spree across New York. It is a landmark film in the rape-revenge subgenre, notable for its grim urban setting, minimalist style, and exploration of vigilante justice through the lens of female trauma. What distinguishes “Ms. 45” from many of its contemporaries is its psychological depth and social critique.

Thana’s silence becomes a potent symbol of women’s voicelessness in a patriarchal, urban landscape saturated with threat. Her transformation from a withdrawn victim into an emotionless executioner mirrors the alienation and rage felt by many women navigating spaces where misogyny is normalized and justice is out of reach. As Thana dons a nun’s costume and opens fire at a Halloween party in the film’s bloody climax, Ferrara blurs the lines between justice, hysteria, and indiscriminate violence. “Ms. 45” critiques both the failure of societal protection and the seductive power of personal vengeance, offering a bleak yet resonant vision of feminist rage turned feral in a world that refuses to listen.

Feminist Reclamations and Ethical Shifts (1980s–1990s)

The 1980s and 1990s witnessed a domestication of the motif. In response to the genre’s excesses, a quieter wave of rape-revenge narratives emerged that emphasized realism, legal critique, and emotional depth. Films like “Extremities” (1986) and “The Accused” (1988) notably shift the locus of revenge from physical retaliation to social and legal confrontation. This shift in focus away from stylized vengeance and toward institutional critique aimed at showing how the justice system retraumatizes survivors and how social norms perpetuate rape culture.

The courtroom drama format of this era functions as an ideological counter to the blood-soaked revenge arc of exploitation cinema. While not revenge films in the traditional sense, they influenced how later directors approached the genre, privileging the survivor’s perspective and interrogating structures of power.

More Related to Female Empowerment in Violent Cinema: Feminism and Its Eternal Affair with Film-making

Robert M. Young’s “Extremities” (1986), based on William Mastrosimone’s stage play, differs from many films in the genre by focusing not on the aftermath of a completed assault. It pivots around the prevention of rape and the volatile confrontation that ensues. Set almost entirely within a single domestic space, it follows Marjorie (Farrah Fawcett), a woman who narrowly escapes a rape attempt by a masked intruder.

When the assailant later breaks into her home again, she manages to turn the tables, capturing him, binding him in her fireplace, and initiating a tense moral and ethical reckoning. “Extremities” transforms the home, typically a symbol of safety, into a claustrophobic battlefield of power, trauma, and control. Rather than relying on stylized violence or exploitation aesthetics, “Extremities” stages revenge as an extended psychological ordeal. It interrogates the ethics of vigilantism and the emotional complexity of trauma-induced rage, refusing the easy catharsis often found in genre fare.

Directed by Jonathan Kaplan and starring Jodie Foster in a career-defining role, “The Accused” (1988) stands apart within the rape-revenge canon by transposing the idea of retribution from the body to the courtroom. Inspired by the real-life 1983 gang rape of Cheryl Araujo in a Massachusetts bar, the film dramatizes the story of Sarah Tobias, a working-class woman who is gang raped while patrons look on and cheer. Rather than exacting personal vengeance, Sarah seeks institutional justice, challenging not just her attackers but the complicit spectators who enabled the crime.

What makes “The Accused” a pivotal film in this genre is its refusal to sensationalize rape for visual spectacle. While the assault is depicted with harrowing intensity, the film’s focus lies in exposing the structural misogyny of the legal system, the media, and public opinion.

The film interrogates rape myths – about clothing, consent, and “respectability” – as Sarah’s character is scrutinized more than the perpetrators. The legal battle shifts the revenge motif from bloodshed to accountability: the climax is not an act of violence, but a rare courtroom victory in convicting the bystanders, marking a profound moment of symbolic retribution. “The Accused” remains significant for articulating a feminist politics of rage without relying on vigilante tropes. It redefines revenge as a demand for systemic reckoning and exposes how rape is perpetuated not only by individuals but by the social and legal frameworks that protect them.

Postmodern Nihilism and the Politics of Excess (2000s)

At the turn of the 21st century, a new wave of European cinema radically reimagined the rape-revenge motif. French films like “Baise-moi” (2000) and “Irreversible” (2002) emerged as part of the so-called “New French Extremity”, a movement characterized by its confrontational aesthetics, corporeal intensity, and refusal of moral clarity. These extreme, postmodern films collapse the boundaries between pornography, art cinema, and political critique.

“Baise-moi,” directed by Virginie Despentes and Coralie Trinh Thi, is a key feminist intervention that is radical in both form and politics. It depicts two women who embark on a spree of sex and murder after enduring rape and systemic degradation. The film rejects narrative coherence and embraces nihilism, depicting its protagonists not as heroines but as instruments of destruction. The film’s unfiltered depictions of unsimulated sex and its punk sensibility reject both victimhood and redemptive narratives. Instead of seeking justice, the protagonists descend into anarchic violence, reflecting not just revenge, but total disillusionment with the social order.

“Irreversible” (2002), directed by Gaspar Noé, by contrast, employs formal experimentation, a reverse chronology, the revenge is shown first, the rape last. The rape scene is shown as a static, nearly 10-minute take after the revenge has already been executed. In doing so, Noé complicates the viewer to confront the horror of trauma without the narrative “justification” typically provided by revenge. Violence in this iteration is irreversible, cyclical, and ultimately devoid of moral satisfaction.

Kinky and allegorical, Mitchell Lichtenstein’s “Teeth” (2007) merges horror and satire in its depiction of a young woman who develops vagina dentate, a literal embodiment of weaponized sexuality. The film turns the rape-revenge arc into a black comedy about sexual agency and male fear.

Contemporary Reconfigurations: Satire, Subversion, and the #MeToo (2010s–present)

The 2010s and 2020s have seen a striking reimagining of the rape-revenge genre, shaped by feminist critique, trauma theory, and the cultural upheaval brought about by the #MeToo movement. In contrast to the visceral spectacle and sensationalism of earlier entries, contemporary films often foreground the emotional, psychological, and social dimensions of gendered violence, interrogating the limits of justice, the complexities of consent, and the cost of revenge.

Contemporary films often reject the simple vengeance arc, instead interrogating the cultural conditions that enable violence and questioning the fantasy of individual justice. These films mark a political turn toward intersectionality, structural critique, and genre deconstruction. Rather than affirming revenge as a form of empowerment, they suggest that true justice lies beyond individual acts of retaliation. The genre is no longer only about the transformation of the victim into an avenger; it is also about the impossibility of closure, the pervasiveness of complicity, and the fragility of redemptive narratives.

Jennifer Kent’s “The Nightingale” (2018) expands the rape-revenge narrative into a brutal meditation on colonialism, racism, and patriarchal violence in 19th-century Tasmania. After being raped and witnessing the murder of her husband and child, Clare (Aisling Franciosi) embarks on a journey of vengeance, aided by an Aboriginal tracker named Billy (Baykali Ganambarr), who has suffered his own systemic abuse at the hands of British colonizers.

Unlike films that glamorize revenge, “The Nightingale” is unrelenting in its realism. The violence is raw and historically grounded, implicating structures of empire, class, and gender. The final act, marked by solidarity between Clare and Billy, gestures toward a different kind of justice, one rooted not in annihilation but in shared survival and recognition of intersecting traumas.

Coralie Fargeat’s “Revenge” (2017) reinvents the rape-revenge narrative through hyperstylized visuals, allegorical excess, and a self-aware reclamation of the male gaze. Set in a sun-drenched desert and dripping with neon gore, the film follows Jen (Matilda Lutz), a young woman left for dead after being raped by one of her boyfriend’s friends.

She survives and returns to hunt down her attackers in a vividly cinematic, almost mythic spectacle. While “Revenge” retains many of the genre’s tropes – sexual assault, attempted murder, survival, and retaliation – it refuses the traditional objectification of the female body. Instead, it embraces a radical physical transformation of Jen, who becomes a bloodied, unstoppable force. The film’s aesthetic excess becomes its feminist statement: violence is rendered so extreme, so theatrical, that it lays bare the absurdity of cinematic conventions that once eroticized women’s pain.

Emerald Fennell’s “Promising Young Woman” (2020) is perhaps the most emblematic post-#MeToo rape-revenge film, leveraging the aesthetics of a candy-coloured rom-com to deliver a bitter, unsettling indictment of rape culture and institutional complicity. The protagonist, Cassie (Carey Mulligan), feigns drunkenness to expose and confront “nice guys” who attempt to take advantage of her. Her tactics are psychological, not physical, until the film’s grim final act, which sees her enact a devastating form of symbolic revenge.

It boasts of tonal instability, oscillating between satire, melodrama, thriller, and tragedy. Fennell deliberately withholds the traditional catharsis of violent retribution, instead presenting revenge as elusive, incomplete, and personally costly. Cassie’s fate underscores the risks women face when they demand accountability, even from systems that claim to protect them. The film’s polarizing ending, where justice is achieved only posthumously, reflects both a deep cynicism and a structural feminist rage that transcends individual vengeance.

Also Related to Portrayal of Female Rage in Movies: The 20 Best Female Filmmakers of All Time

Canadian indie “Violation” (2020) presents one of the most psychologically complex and formally experimental entries in recent memory. The film rejects genre convention by immersing the viewer in the fragmented subjectivity of its protagonist, Miriam (Madeleine Sims-Fewer), who is raped by her brother-in-law Dylan (Jesse LaVercombe). Her act of revenge – violent, prolonged, and emotionally hollow – is depicted in nonlinear, elliptical narrative sequences that emphasize the mental dislocation of trauma.

Socio-Political Impact of Rape-Revenge Films

Rape-revenge films are often criticized for sensationalizing sexual violence, reducing it to a narrative device that serves voyeuristic or exploitative ends. Particularly in earlier grindhouse and exploitation cinema, depictions of rape were often prolonged, explicit, and stylized, raising questions about the ethics of representation, audience complicity, and the re-traumatization of survivors. However, the genre has also served as a site of feminist intervention, giving form to suppressed rage and offering space for female agency, resistance, and catharsis.

Second-wave feminists often viewed the rape-revenge genre as a space of catharsis, transforming passive victimhood into active agency. In her seminal work Rape Revenge: A Critical Study, Alexandra Heller Nicholas contends that the early cycle of rape-revenge films may be interpreted as cinematic attempts to “make sense of feminism” as it arose during the 1970s.

This narrative structure foregrounds a significant transformation, typically unfolding between the first and final acts, wherein the protagonist’s shift from a passive victim to an empowered avenger can be read as a symbolic transition from a traditionally feminine identity to one informed by feminist consciousness.

Later feminist critiques, however, highlighted the genre’s problematic tropes: the idealization of violent revenge, the glamorization of trauma, and the perpetuation of voyeuristic representations of rape. Films like “Ms. 45,” “The Accused,” “Teeth,” and “Promising Young Woman” have challenged the passivity traditionally assigned to female characters, instead portraying women who confront or overturn their trauma through various forms of retaliation or legal reckoning.

These films often provoke urgent conversations around consent, rape culture, systemic injustice, and the failures of legal and institutional accountability. Moreover, the rape-revenge narrative has evolved to reflect shifting socio-political climates. In the post-#MeToo era, the genre has become a crucible for exploring collective trauma, feminist rage, and institutional complicity, as seen in films like “The Nightingale,” “Violation,” and “Revenge.” These works resist simplistic notions of justice, instead interrogating the emotional, ethical, and systemic complexities that surround sexual violence.

Ultimately, rape-revenge films function as cultural barometers, revealing how societies imagine, police, and politicize sexual violence. Their controversial and often polarizing nature ensures their continued relevance, not as straightforward vehicles of empowerment or exploitation, but as contested texts through which gender, power, and justice are dramatically negotiated.

Aesthetics and the Problem of Representation

The rape-revenge genre has long been entangled in fraught debates around visual representation, cinematic ethics, and the politics of spectatorship. From the visceral, grainy aesthetics of 1970s exploitation cinema to the hyper-stylized, reflexive approaches of contemporary auteurs, the genre’s form has often determined its critical and political reception as much as its content.

In early examples such as “I Spit on Your Grave” (1978) and “The Last House on the Left” (1972), aesthetics veered toward raw, unflinching realism. These films often lingered voyeuristically on the rape scenes, leading to accusations of exploitation despite their feminist intentions or subtexts. The low-budget, grindhouse aesthetic created a disturbing proximity between viewer and violence, collapsing the boundary between critique and consumption. Yet this very discomfort became a strategy, forcing audiences to confront, rather than aestheticize, the brutality of sexual violence.

In contrast, films like “Ms. 45” (1981) or “Thriller: A Cruel Picture” (1973) adopted more stylized approaches, using urban landscapes, silence, and slow motion to heighten affective intensity. Here, aesthetics served both to alienate and empower, elevating the protagonist’s trauma into a visual spectacle while also crafting moments of feminist resistance through form.

By the 2000s, directors like Gaspar Noé (Irreversible, 2002) and Virginie Despentes (Baise-Moi, 2000) deliberately blurred the boundaries between pornography, art cinema, and political critique, destabilizing the audience’s moral and visual comfort. These films complicated any easy reading of vengeance or victimhood, using non-linear narratives, handheld camerawork, and fragmented timelines to evoke disorientation and trauma.

In the post-#MeToo era, aesthetics have evolved once again. Films like “Revenge” (2017), “The Nightingale” (2018), and “Promising Young Woman” (2020) deploy striking visual language – neon palettes, horror tropes, revisionist period drama – as tools of subversion. In these works, the problem of representation is acknowledged and often thematized: rape is sometimes elided or shown obliquely, with emphasis shifting from the act itself to its emotional, legal, and cultural aftermath. The focus has moved from exploitation to introspection, from shock to critique.

Read More Related to Revenge Cinema: 10 Best Films Dealing with Toxic Work Culture

The rape-revenge motif remains one of the most morally and aesthetically charged genres in cinema. Throughout its trajectory, the genre remains haunted by the paradox of representing sexual violence on screen, how to depict rape without reproducing its trauma or inviting voyeurism; how to frame revenge without glorifying violence.

The aesthetics of rape-revenge cinema, in their shifts and contradictions, reflect this ongoing struggle to ethically visualize one of society’s most painful realities. As feminist theory continues to shape and challenge cinematic discourse, the rape-revenge narrative will remain a vital, if contested, space for exploring the politics of the body, the ethics of representation, and the enduring struggle for agency and dignity.