A very real argument can be made—and, on many occasions, has been made—that Martin Scorsese is the greatest film director of all time; of the modern day, at the very least. A filmmaker of uncompromising brutality and equally relentless empathy, Scorsese’s love of the medium that made him shines through in every frame of his work, displaying a versatility that never betrays the biting wit and textured sense of place and time that permeates even his less revered work.

To that end, the consistency in the quality of the Italian-American auteur’s work is nigh unmatched by his contemporaries; the likes of Spielberg and Coppola can all attest to having a few duds in their adventurous careers, Scorsese’s catalogue is nearly blemish-free… nearly (hello, “Boxcar Bertha”).

Skeptics would argue that Scorsese’s cinema is a cinema of repetition, that his recurring interest in gangster life is the sign of an artist with little novelty to say. But these arguments wilfully ignore the varied perspectives Scorsese brings to these ostensibly similar fields of storytelling, and in these continued explorations, the director cements the rigor of his burning desire to revisit these fields every so often with a new set of eyes. In even the most commercial of his features, Scorsese has never implemented any less than 100% commitment to the craft, and in examining his 15 best films, this truth remains ever-clear.

15. The Age of Innocence (1992)

Nobody who accuses Scorsese of having made “the same film over and over again” ever seems to account for the existence of “The Age of Innocence”; it then stands to reason that most of these ignoramuses have never even heard of the film, let alone seen it. Possibly the wildest departure from the blood-fueled gangland epics for which he is most known, Scorsese’s period romance oozes with repressed longing as he examines the place of his birth and the true love of his life, New York City, through the lens of 1870s class elitism.

Dipping his toes into Merchant-Ivory elegance, “The Age of Innocence” guides us through the barriers of romance carried by reputation, as Daniel Day-Lewis weaponizes one of his most clenched performances to fully inhabit the frustrations of the day, all for a demographic so difficult to empathize with.

One of Scorsese’s greatest storytelling strengths has always been his willingness to explore the most untouchable heights of the social ladder and find whatever crumbs of sympathy could be found, without ever losing sight of the privilege and seediness that keep them there. In the sight of old-money families, “The Age of Innocence” finds its tenderness even in the most uptight of crevices.

Also Read: 10 Best Daniel Day-Lewis Performances

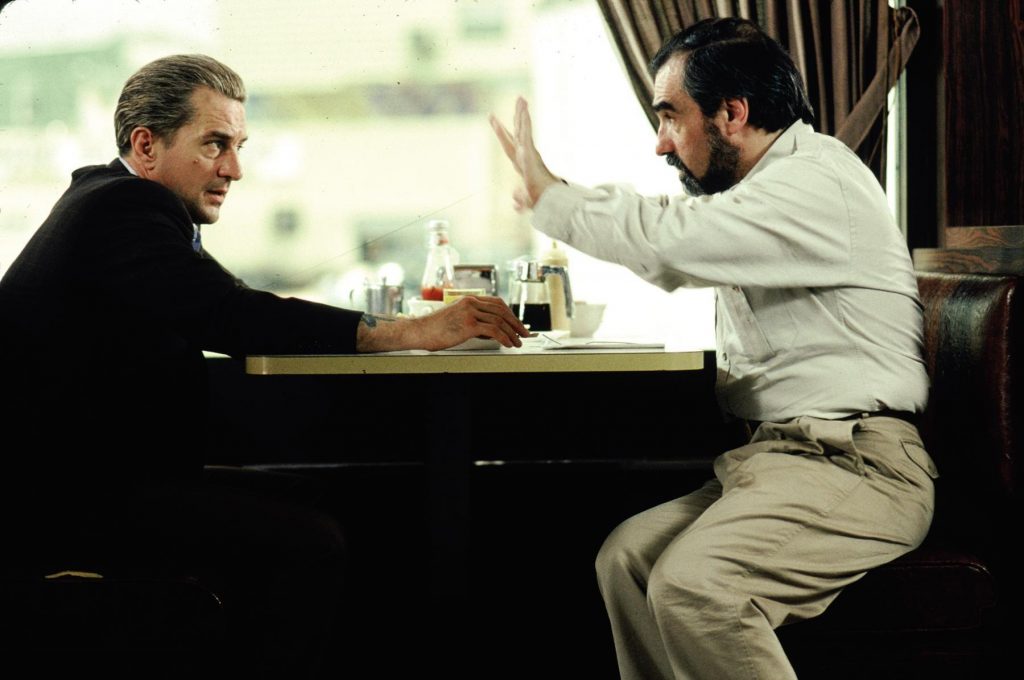

14. Casino (1995)

The first of several gangster films to appear on this list—and, for a good while, the last Scorsese film to feature his greatest muse Robert De Niro—”Casino” may not hold the same cultural footprint as the filmmaker’s most celebrated views behind the barrel of a gun, but even the director’s beefiest marathons (this one just shy of three hours) fly by thanks to the effortless flair of Thelma Schoonmaker’s miraculous editing. Re-teaming with De Niro and Joe Pesci, Scorsese finds in “Casino” among the most repugnant of America’s gangsters, particularly because theirs is a playground so widely embraced as a touchstone of life in Las Vegas.

Not only does “Casino” make pertinent use of Scorsese’s regulars, but in it the director finds the room to play with a whole new field of willing participants, each one of them adding an unexpectedly rich dimension to this new shade of familiar gangster’s paradise. Sharon Stone, Don Rickles, and even James Woods all assemble to form essential cogs in the Vegas slot machine that chews us all up and spits us out as those scant few pennies with which the pit boss is ever willing to part ways.

13. Killers of the Flower Moon (2023)

To date, the most recent and longest of Scorsese’s pictures, “Killers of the Flower Moon,” stands as a milestone statement from a filmmaker who’s always been adept at dissecting the horrors of American privilege, but never to degrees so fundamentally sewn into the nation’s fabric.

The first union between the director’s longstanding partners—De Niro, Schoonmaker, and Leonardo DiCaprio—the film finds all three in peak form as Scorsese harnesses their collective willingness to explore new depths of ugliness in the nation they all call home. While Schoonmaker makes three-and-a-half hours feel like just over half as long, De Niro and DiCaprio each inhabit different poles of that ugliness to illustrate where deception is America’s most rewarded vice, and its greatest tool for destruction.

Lily Gladstone joins the fray to go toe-to-toe with her veteran costars and adds a much-needed anchor to the film’s admirable empathy with Indigenous American resistance in the face of exploitation. Like her people, Gladstone is never ignorant to the horrors perpetrated by the white man, but her eternal capacity for grace and empathy proves misplaced in the offer for them to prove her instincts wrong. The actor’s subsequent ability to distill this embedded disappointment in the nuances of an unchanging expression proves to be the lifeforce of a film that finds in that disappointment the perseverance to remain, when all others try to uproot one from their rightful land.

Related Read: 10 Best Leonardo DiCaprio Performances

12. After Hours (1985)

You may notice a recurring depiction of New York City in Martin Scorsese’s cinema, but few films have distilled the essence of the city that never sleeps quite like “After Hours.” And by that, I of course mean the essence of an absolute shitstorm of confrontation, makeshift exuberance, and the drive of a blind libido. Starring Griffin Dunne (or, as I like to call him, Not Quote Noah Baumbach), the film takes the everyman conduit and injects him with Scorsese’s usual bout of slime to make his journey through the nighttime concrete jungles one that keeps the “I’m walkin’ here!” of it all eternally close to the chest.

On an endless chase through those rain-coated streets, Scorsese never forgets that at the core of “After Hours” is a hearty injection of absurd comedy, ensuring that this greasy view of his hometown is never anything less than a letter of love, signed with the sweat of an office worker who just wanted to get some tail before the zombified trek to work the next morning. We’ve all been there, and Scorsese captures that feeling with such a distinct grasp of his setting that we’re only left to marvel at the fact that we haven’t actually run from an angry mob or casually seen a woman violently shoot her boyfriend through the window of an abandoned building.

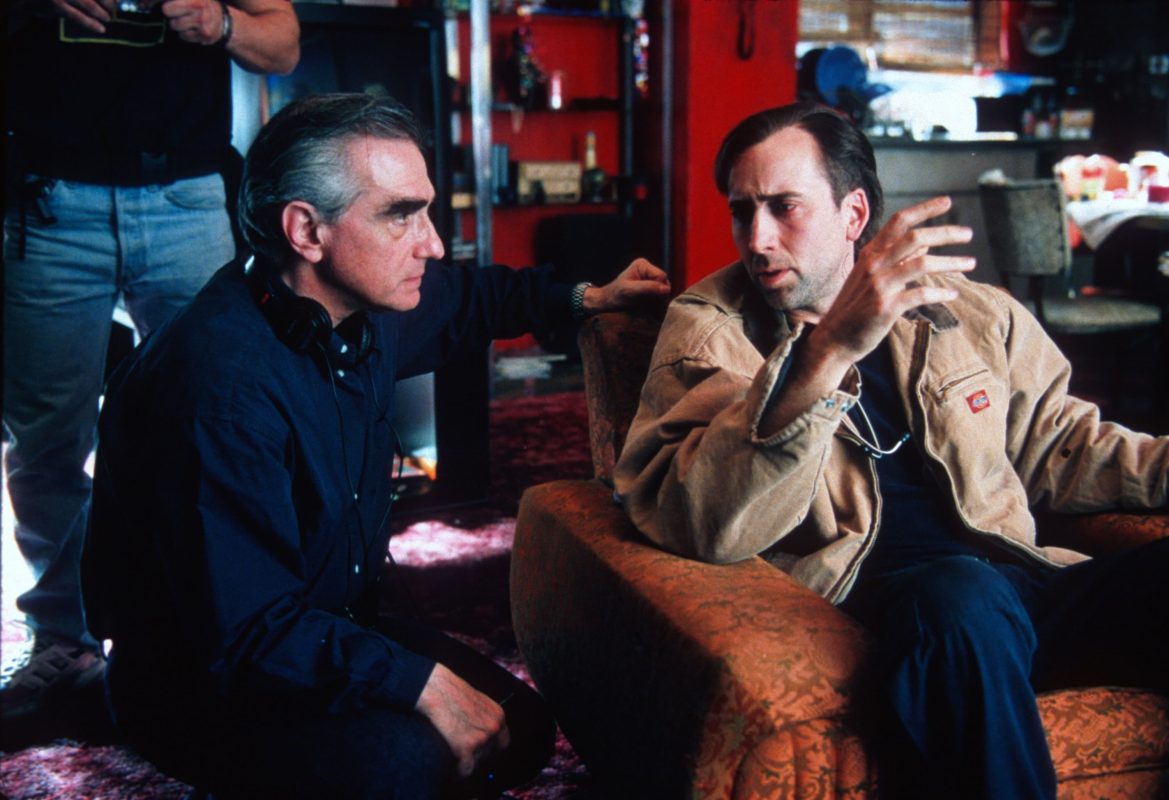

11. Bringing Out the Dead (1999)

Scorsese is one of those rare auteurs who rarely has a hand in writing his own screenplays (officially, at least), and in Paul Schrader, the director found his most consistently provocative collaborator. “Bringing Out the Dead” constitutes both the final and the least revered of the Scorsese/Schrader unions, but it nonetheless constitutes yet another window into the eternal migraine that is New York City’s nightlife, all through the perspective of one of the most thankless professions imaginable: a metropolitan paramedic.

That such a soldier for New York’s seediest and least appreciative corners is played by Nicolas Cage is just the icing on the cake, as the wild icon perfects the disposition of a sleepless public servant who sees in his nightly excursions only the blinding illusion of street lights swaying past his increasingly decaying peripheral line of sight. Always at risk of crumbling under the weight of its own cumbersome drive to move along without feeling, “Bringing Out the Dead” continuously keeps one finger on the pulse of the world that keeps this beleaguered worker driving on, with no real end to the journey in sight. This ambulance is on a direct route through Hell, and we’re all riding shotgun.

Check Out: 15 Best Nicolas Cage Performances

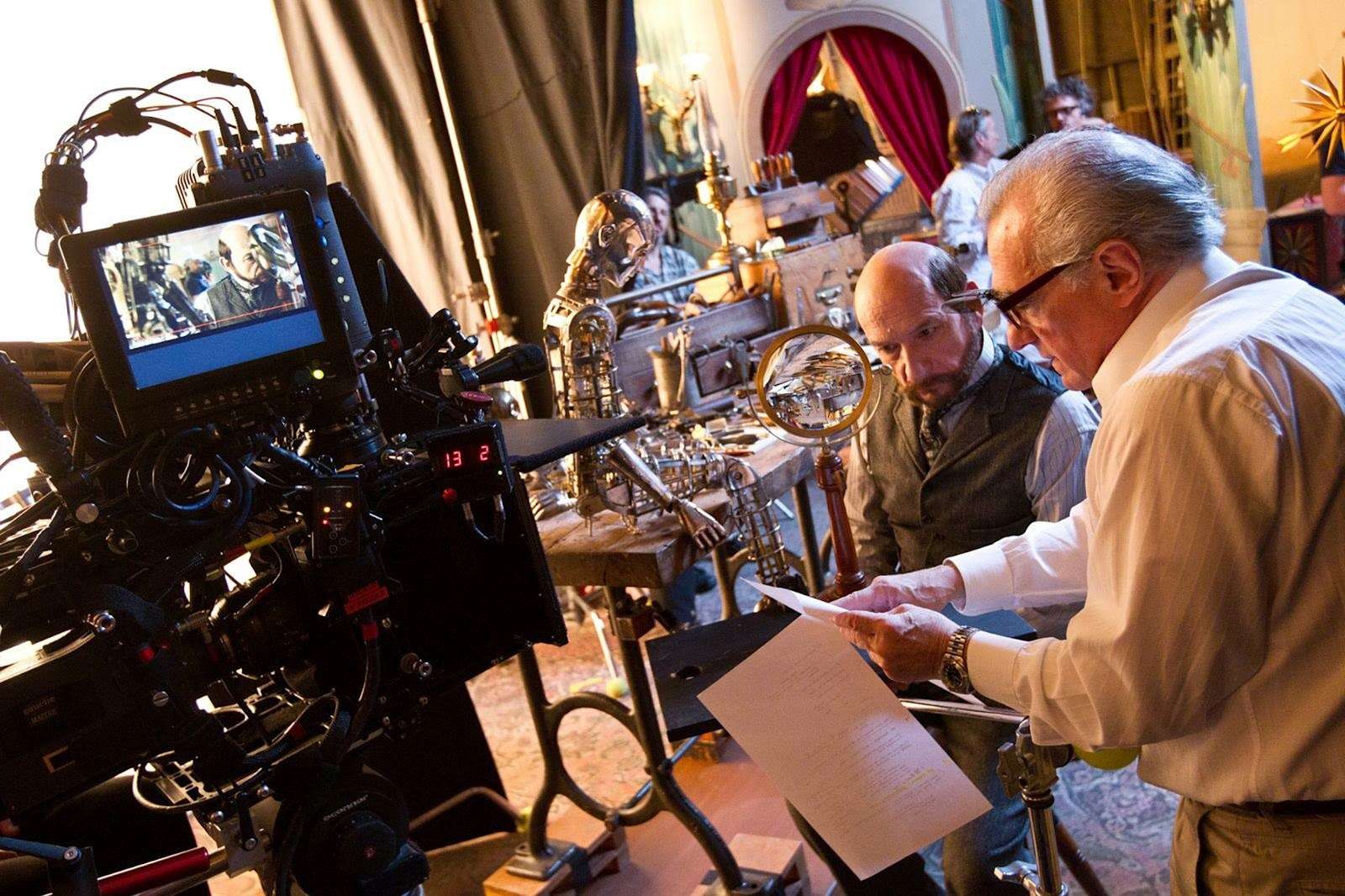

10. Hugo (2011)

Perhaps the most noticeable outlier in Scorsese’s otherwise-adult-oriented filmography, “Hugo” may initially appear to be a complete question mark, or the studio-mandated work of an auteur invoking the classic “one for them, one for me” routine. Upon closer inspection, however, nobody but Scorsese could have made this film, and it’s difficult to imagine the average child losing their minds over a love letter to Georges Méliès and the earliest days of silent cinema. Scorsese, of course, keeps his focus not on pleasing the youth but rather on offering them a gentle nudge towards a more appreciative and involved view of the art form that has surrounded them from their youngest days.

“Gentle,” really, is the most apt adjective to describe “Hugo” from beginning to end, which is itself a concept entirely unimaginable for a filmmaker whose joys otherwise skew closer to the hefty Italian meals eaten after a rival’s brutal beatdown. Above all his own creative inclinations, though, lies Scorsese’s undying reverence for cinema as a formative experience in his own life, and “Hugo” exists as a welcoming hand extended to guide us all to a more conscious respect for the joys we all experience, and the painstaking efforts made to bring them to us.

While You’re Here: 5 Important Georges Méliès Films You Should Watch

9. Silence (2016)

One theme in Scorsese’s work that has so far gone unremarked on this list is the director’s persistent grappling with his Catholic faith. Having once decided to be a priest, this vocation quickly fell to the wayside when his own uncertainties began to take root above blind devotion. This has, naturally, led to some of the director’s richest and most fulfilling features, and “Silence” stands as one of the very richest examinations of a crisis of faith—by Scorsese, or by anyone. In it, too, are the inklings of colonialist guilt that would take even greater hold in “Killers of the Flower Moon,” while here taking shape in a more deceptively peaceable fashion.

Exploring and subsequently exploiting the serenity of its Japanese locale, “Silence” finds Scorsese grappling with Catholic guilt with a real hands-on attitude that, nonetheless, is anchored by the sagacity of a veteran who knows, by this point, how to express this conflicting state with effortless nuance. Experience and wisdom don’t mean peace of mind, however, and “Silence” illustrates this frustration as Scorsese winds his way through the valleys of his own faith with merely a greater understanding of how to appreciate their dimension, rather than a concrete understanding of where those valleys end.

Also Read: 10 Best Andrew Garfield Performances

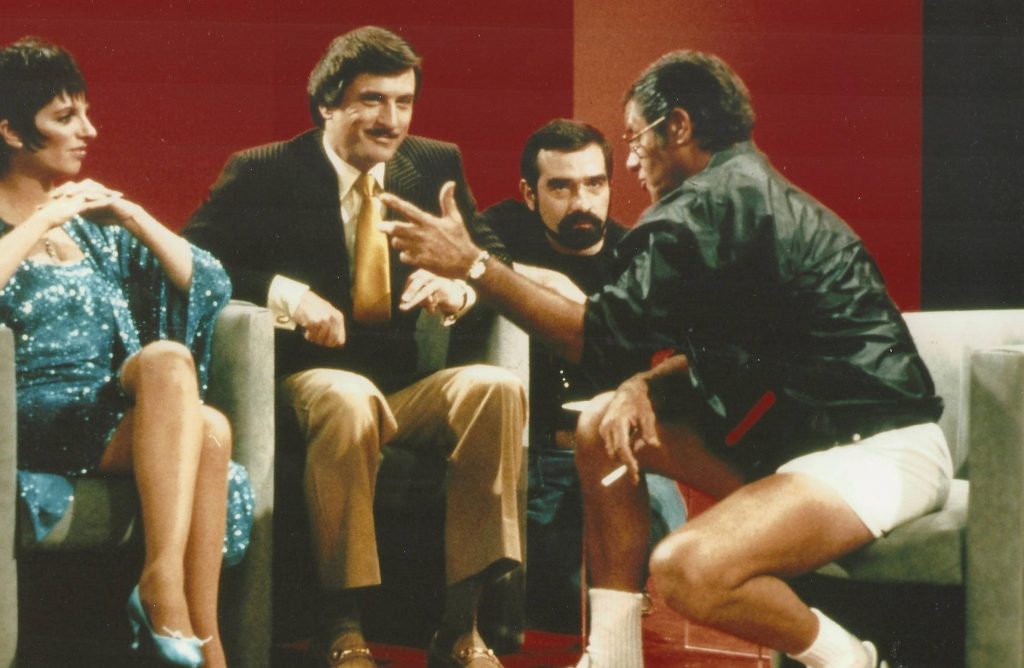

8. The King of Comedy (1982)

The shortest way to explain the value of “The King of Comedy” would be to recite any of the existing defenses of “Joker” as a piece of thematically dense filmmaking, and then pitch a film that did all of that first… and, you know, for adults. It’s honestly astonishing how much of this film Todd Phillips got away with directly cribbing, but none of that takes away from the fact that Scorsese’s less widely revered picture is ever more rewarding because of its refusal to conform to simplified mandates of audience approval. It’s prickly, it’s uncomfortable, and it’s everything a view of unhinged delusions of grandeur should be.

In a sense, this makes “The King of Comedy” extremely prescient to our current moment of internet-propelled stalker behavior, and Robert De Niro consequently gives one of his scariest performances as an unhinged fan who simply can’t grasp the concept of boundaries and his own limitations. Weaseling his way through the film with the most effortlessly effortful smile this side of the ‘80s, De Niro navigates one of the trickiest protagonists in American studio filmmaking precisely by refusing to take his mental difficulties to the realm of awards-bait. All you need to set audiences on edge is the smiling mask of self-delusion, exactly as it appears.

7. The Departed (2006)

The film that finally won Scorsese his long-awaited Oscar for Best Director, it’s easy to look upon “The Departed” as little more than the culmination of a career narrative for belated awards attention. In remaking the Hong Kong police classic “Infernal Affairs,” Scorsese nevertheless finds his own perceptive view of what life in the trenches of mobster life can truly look like. Slick as ever but never glamorized, Scorsese’s Boston-bound view of competing informants excels most in its sense of gritty urgency because the toll taken on those involved becomes increasingly suffocating beyond the point of endurance.

DiCaprio once again stars alongside one of Scorsese’s most robust casts (2000s Jack Nicholson sighting!), letting every ounce of his character’s burdensome weight slowly press down on his chest until his eyes are ready to pop right out of their sockets, and his finger is ready to squeeze the trigger prematurely. Any such move, though, means an instant and unceremonious end in “The Departed,” and Scorsese’s meticulous crafting of this continuous death trap removes any sense of valorization from this petrifying view of life as a two-bit thug—or an increasingly disillusioned cop who thinks he can bring it all down.

Also Read: 10 Best Jack Nicholson Performances

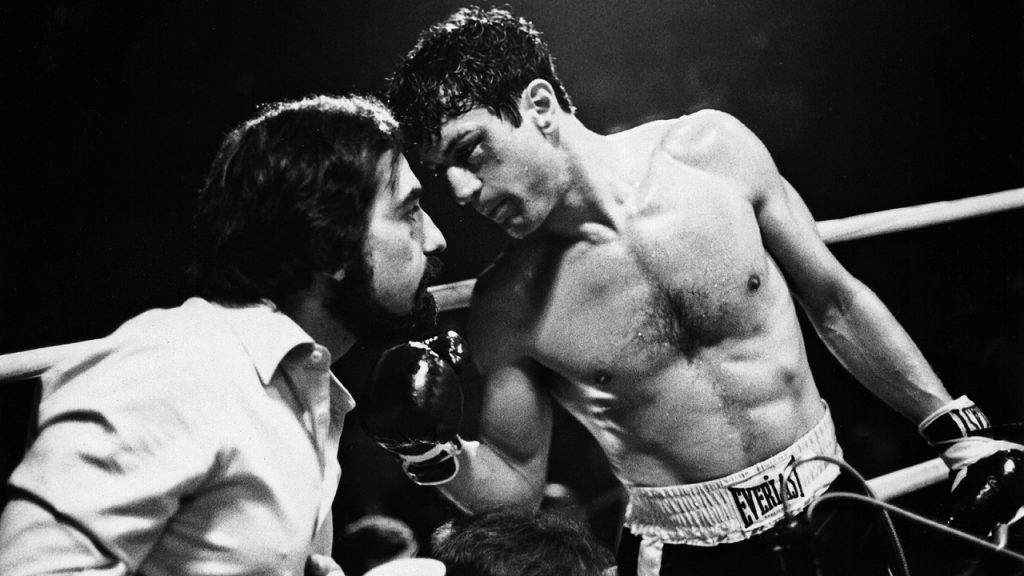

6. Raging Bull (1980)

Robert De Niro won the second of his two Oscars for playing Jae LaMotta in “Raging Bull,” and the transformation onscreen is nothing short of disarming. In a film so thoroughly steeped in the ugliness of success, Scorsese’s unrelenting portrait of LaMotta’s battles within and beyond the boxing ring is akin to a glimpse into the most passive but blinding of evils. De Niro bobs and weaves his way through LaMotta’s life with nary a moment to give him charm, but still affords endless grace to find the truth in his insecurities that never allow this vision to feel like a caricature.

Once again, it’s the union of Scorsese, De Niro, and Schoonmaker that makes the magic flow, as “Raging Bull” captures the energy of the ring in tandem with the refinement of a meticulous dance, in all cases leaving the ground peppered with sweat, spittle, and blood. Allegedly, LaMotta—who trained De Niro for his boxing scenes—was so taken aback by the film that, after the credits had rolled, he turned to his wife and asked her if he had truly been so monstrous during their time together. “No,” she said. “You were worse.”

5. The Wolf of Wall Street (2013)

Never has the war against media illiteracy been waged as vigorously—and, as it would seem right now, as futilely—as in the ongoing appraisal of “The Wolf of Wall Street.” Why that is, however, is fairly understandable given how relentlessly fun Scorsese makes the hedonistic lifestyle of Jordan Belfort appear. It’s more of a testament to the growing culture of late-stage capitalist delusion and greed than any fault on Scorsese’s part, as the film takes more than a fair share of its runtime exploring the complete moral decrepitude that lies at the core of Belfort’s existence.

This is, in large part, thanks to the most slimily alluring Leonardo DiCaprio performance we’ve yet seen, but just as critical to this highwire tonal balancing act is the contribution of the film’s unsung hero, Terence Winter. A screenwriter who’s sadly relegated his talents primarily to television, Winter’s endlessly quotable and dynamically structured script brings the same sticky appeal he lent to so many of the best episodes of “The Sopranos,” reminding us at every turn how much we should hate ourselves for laughing alongside the extravagance of Belfort’s sociopathic gluttony, given its full due by a filmmaker always ready to fire the confetti cannon directly into the viewer’s face.

Must Read: 75 Best Films of the 2010s Decade

4. The Irishman (2019)

By 2019, the prospect of another gangster film for Martin Scorsese’s resume appeared, to the uninitiated, a tired proposition. What more could the man possibly have to say about a milieu he’d already explored so thoroughly? As it turns out, a whole hell of a lot! Assembling a true murderer’s row of gangster cinema veterans—his first collaboration with De Niro since “Casino,” his first collaboration with Al Pacino at all, pulling Joe Pesci out of retirement—”The Irishman” acts as Scorsese’s elegy to the heyday of organized crime, with perhaps the most honest depiction of its moral vacuity ever put to screen. Not a second of its three-and-a-half-hour runtime is put to waste, as Frank Sheeran’s disputed exploits in the Philadelphia mob reward every moment of patience you give them.

This proves truest in the film’s blistering final act—potentially the greatest denouement of Scorsese’s entire career—wherein “The Irishman” truly sells the internal rot that comes with the territory, and Sheeran begins to reckon with the loneliness of the loyalty he’s chosen to uphold when it’s all said and done, and nobody remains to moderately praise him as a faithful lapdog. In the still of the night, all that’s left to be heard is the silence of your own lacking conscience.

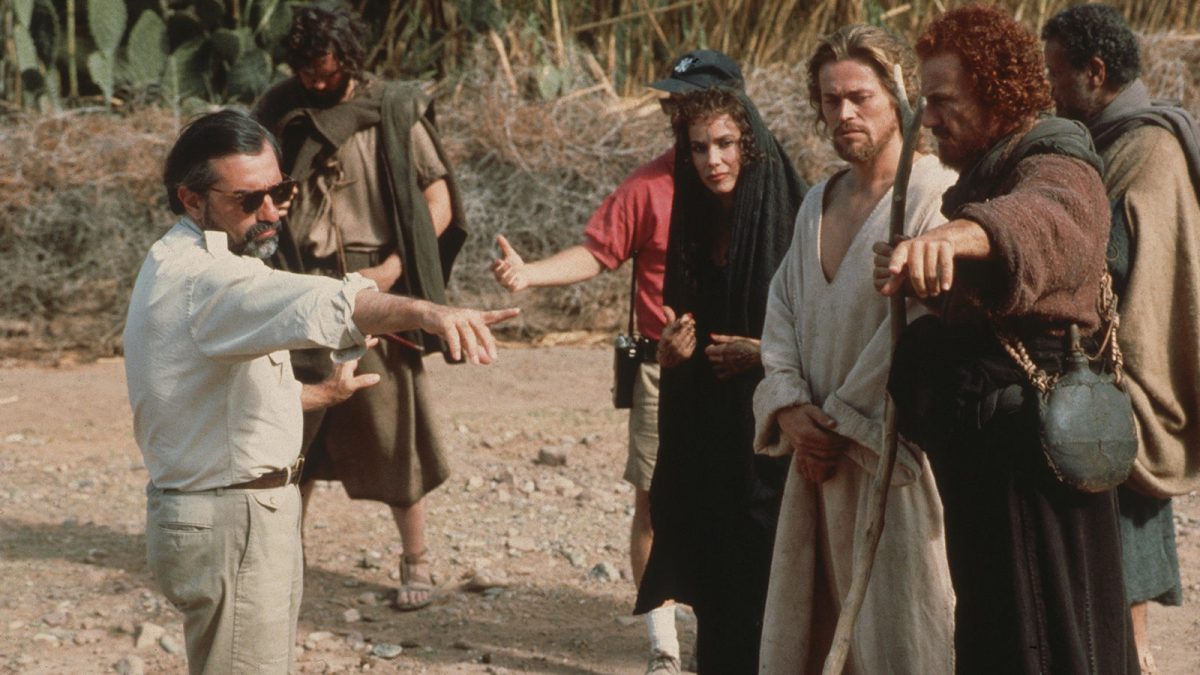

3. The Last Temptation of Christ (1988)

As Scorsese and Paul Schrader would continue their intermittent partnership with acidic interrogations of flawed men, the former’s ever-present crisis of faith would help them drum up the most fundamental examination of flaw, by way of the most ostensibly flawless person who ever (supposedly) walked the Earth (…and on water).

“The Last Temptation of Christ” was immediately controversial upon release for deigning to imagine Christianity’s central figure as a mere human being who struggled with the allure of human vice. And this focus on Jesus’s flaws as a figure of inimitable influence is, naturally, precisely what makes this film just about the only interesting depiction of the being ever put to screen.

Armed with an unfailingly dynamic Willem Dafoe performance at its center, Scorsese’s most direct confrontation of his faith proves his loyalty to the faith more than any amount of blind prayer ever could. “The Last Temptation of Christ” finds in this persistent pushback the drive to turn doubt into devotion, and ask the very questions that make a journey towards enlightenment the least bit rewarding in the cuts and bruises that appear on his feet as he walks the path so few are willing to tread.

2. Goodfellas (1990)

Alright, ONE last gangster flick for the road. At this point, though, you can’t really fault us for forcing “Goodfellas” into a Scorsese ranking, as it may very well be the defining Scorsese film just as much as it may be the defining post-”Godfather” gangster film. Why that is comes down to the perfect confluence of everything that has made Scorsese so unimpeachable as a filmmaker thus far: laser-focused craft, considered casting, and a thoroughly embedded desire to avoid letting the allure of his subject matter distract from the apathy required to attain it.

Completely embodying the slickness of a crew that dresses in three-piece suits just to hang out behind a butcher shop every weekday, “Goodfellas” foregrounds the moral damnation of its protagonist to expand upon maybe Scorsese’s most prevalent theme: self-preservation. What self-preservation does to a man—what it motivates him to do in the name of his own hungers and ambitions—changes wildly when the shadow of the gun grows slowly against the wall, and Scorsese’s decision to unpack these memories of those that surrounded him in his childhood turn the unattainability of success in organized crime into a Shakespearian fable, ending in the spilling of hot noodles and ketchup.

While You’re Here: 10 Facts You Probably Didn’t Know About ‘Goodfellas’

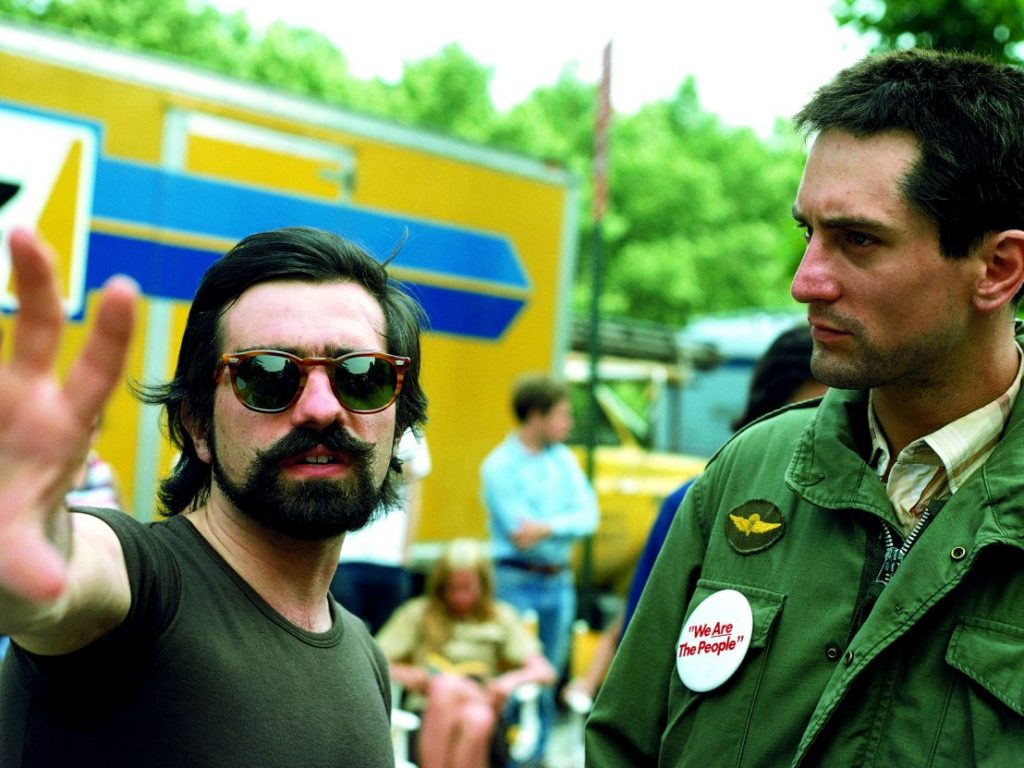

1. Taxi Driver (1976)

In essence, Paul Schrader’s entire career as a writer-director finds its blueprints in what his screenplay for “Taxi Driver” had perfected: the man in a room writing in a diary. The fractured psychology at the core of this film is precisely what Schrader’s script finds so worth exploring in the finer details of Travis Bickle’s flawed rationalizations of the decrepitude around him, just as it is Scorsese’s fascination with turning that paranoia into a visualized psychosis that makes the film such an enduring piece of New American cinema.

The most potent examination of male inadequacy ever born from a country that breeds fallible masculinity like farms breed chickens, “Taxi Driver” shows how the scum of the streets can’t be washed away with the rain, especially when the ones yearning to do the cleaning have an internal rot of their own in desperate need of burning away.

De Niro’s career-best performance brings unassuming life to this internal conflict, affording Scorsese the opportunity to be the most painfully honest he’s ever been about the state of America in an age of rupturing illusions of vigilantism. One ride through the streets is all it takes to conclude that nothing substantive can be done from the side of the curb, except fight to keep yourself from finding refuge in its darkest corners.