Sidney Lumet was a giant of American cinema, carving out a remarkable career spanning six decades and leaving an indelible mark on the landscape of film worldwide. From his electrifying debut in the 1950s to his final masterpiece in the late 2000s, Lumet consistently delivered works that challenged, provoked, and enthralled audiences. Critics and audiences from Europe to Asia found themselves captivated by Lumet’s unflinching portrayals of institutional corruption, personal ethics, and the often murky waters of the American Dream.

Lumet proved to be a master of creating tension through dialogue and character interaction, often eschewing flashy camera work in favor of simple and effective compositions that drew viewers into the psychological space of his characters. His New York-set films captured the city with a gritty authenticity that became a hallmark of his work, turning locations into characters in their own right. Influenced by his early work in television and theater, Lumet’s background gave him a keen understanding of how to block scenes for maximum dramatic impact and how to draw nuanced performances from his actors. He was known for his extensive rehearsal process, which allowed his ensemble casts to develop a lived-in quality that translated beautifully to the screen.

One could often find in Lumet’s films a visual evolution that mirrored the narrative arc. He would subtly adjust framing, lighting, and camera movement as the story progressed, creating a subconscious emotional journey for the viewer. This technique, while never calling attention to itself, added layers of depth to his storytelling. In this article, we explore the 15 best movies from Sidney Lumet’s illustrious career. Enjoy!

15. The Offence (1973)

Set in a gloomy English town, “The Offence” follows Detective Sergeant Johnson (Sean Connery), a seasoned police officer whose grip on reality begins to unravel after years of confronting society’s most depraved criminals. Lumet presents the plot in a non-linear fashion, opening with a shocking scene of violence: Johnson savagely beats a suspect in an interrogation room. We’re then taken back in time to piece together the events leading up to this brutal act. A young girl has been assaulted in a local park, and Johnson is assigned to the case. As he investigates, we see glimpses of his troubled home life with his wife, Maureen (Vivien Merchant), hinting at his work’s toll on their relationship.

The investigation leads to the arrest of Kenneth Baxter (Ian Bannen), a mild-mannered man who becomes the prime suspect. Johnson’s interrogation of Baxter forms the film’s centerpiece – a riveting, claustrophobic battle of wills that pushes both men to their psychological limits. As the questioning intensifies, the lines between interrogator and suspect blur, with Johnson’s own repressed demons bubbling to the surface. Lumet expertly ratchets up the tension through tight close-ups and oppressive silences. The dingy, fluorescent-lit interrogation room becomes a crucible for Johnson’s inner turmoil, with Connery delivering a tour de force performance that shatters his suave James Bond image. His Johnson is a powder keg of rage and self-loathing, barely held in check by a veneer of professionalism. Lumet poses uncomfortable questions about the thin line separating those who uphold the law from those who break it.

14. Equus (1977)

Adapted from Peter Shaffer’s acclaimed stage play, “Equus” offers a haunting and provocative exploration of the human psyche. The film centers on Alan Strang (Peter Firth), a troubled 17-year-old who has committed the horrifying act of blinding six horses with a metal spike. Enter Dr. Martin Dysart (Richard Burton), a world-weary child psychiatrist tasked with unraveling the enigma of Alan’s disturbed mind. Through a series of intense therapy sessions, Dysart attempts to unravel the complex web of motivations that led to Alan’s horrific act. As the layers of Alan’s mind are peeled back, Dysart finds himself on a perilous journey that challenges his own beliefs about reason and spirituality.

The film’s structure oscillates between Dysart’s present-day sessions with Alan and vivid flashbacks that gradually reveal the boy’s troubled past. This non-linear approach keeps viewers on edge, piecing together the puzzle of Alan’s psychosis alongside Dysart. We learn of Alan’s stringent upbringing, torn between his atheist father, Frank (Colin Blakely), and devout Christian mother, Dora (Joan Plowright). Their conflicting ideologies create a pressure cooker of repression and guilt in young Alan’s mind. His discovery of an ecstatic, quasi-religious connection to horses becomes both his salvation and his undoing. The film’s pivotal scenes in the stables are nothing short of mesmerizing, with Lumet employing surrealist dream-like imagery to capture Alan’s rapturous communion with the horses. The pounding of hooves becomes a primal heartbeat, and the stable is a pagan temple where Alan worships his equine gods.

13. Deathtrap (1982)

Lumet’s “Deathtrap” is a deliciously twisted tale of murder, deceit, and the cutthroat world of Broadway theater. Based on Ira Levin’s long-running play, this wickedly clever thriller keeps audiences guessing until the final curtain, blurring the lines between reality and fiction with gleeful abandon. At its heart is Sidney Bruhl (Michael Caine), a once-successful playwright now languishing in a creative drought. Desperate for a hit, Sidney hatches a diabolical scheme when he receives a brilliant script from a former student, Clifford Anderson (Christopher Reeve). With the reluctant complicity of his anxious wife Myra (Dyan Cannon), Sidney invites the unsuspecting Clifford to their isolated Long Island home, intent on murdering him and stealing his play.

What follows is a masterclass in misdirection and narrative sleight-of-hand. Just when you think you’ve got a handle on the story, Lumet pulls the rug out from under you, sending the plot careening in unexpected directions. He transforms the Bruhls’ rustic home into a claustrophobic arena where wordplay becomes weaponry, and every prop carries ominous potential. The director’s restless camera prowls the house like an unseen conspirator, finding fresh angles to amp up the tension in what could have been a visually static adaptation. At its core, “Deathtrap” is a biting satire of the creative process and the lengths to which artists will go for success. Sidney’s willingness to literally kill for a hit play speaks to the cutthroat nature of show business, while the constant blurring of reality and fiction suggests the thin line between inspiration and madness.

12. Prince of the City (1981)

Based on Robert Daley’s book about real-life NYPD detective Robert Leuci, “Prince of the City” is a gritty look at the thin blue line that separates law enforcement from the criminals they pursue. Danny Ciello (Treat Williams) is a narcotics detective who’s part of an elite unit known as the Special Investigations Unit (SIU). He’s a charismatic, street-smart cop who’s not above bending the rules to get results. But when federal investigators approach him about cooperating in a probe into police corruption, Danny faces an excruciating dilemma. Initially reluctant, Danny eventually agrees to wear a wire and inform on his fellow officers, but with one condition: he won’t give up his partners or his family.

What follows is a grueling years-long investigation that slowly unravels Danny’s life and his erstwhile binary understanding of right and wrong. Working from a screenplay he co-wrote with Jay Presson Allen, Lumet crafts a dense and intricate narrative that mirrors the complexity of the case itself. The film runs nearly three hours without ever feeling bloated. Instead, it allows us to fully immerse ourselves in Danny’s world, feeling the weight of each compromising decision and the slow erosion of his moral certainty.

We watch as Danny’s initial righteousness gives way to doubt, paranoia, and, ultimately, a kind of broken resignation. Trent Williams makes Danny’s journey visceral and heartbreaking, showing us a man torn apart by conflicting loyalties. Cinematographer Andrzej Bartkowiak bathes New York in a palette of greys and muted colors, creating a world where moral absolutes blur into shades of compromise. The city itself becomes a character, its gritty streets and imposing institutions looming over Danny like silent judges.

11. Long Day’s Journey into Night (1962)

A searing, unflinching adaptation of Eugene O’Neill’s autobiographical masterpiece, Lumet’s “Long Day’s Journey into Night” is a cinematic tour de force exploring addiction and familial dysfunction over a single grueling day in the life of the Tyrone family. Set in 1912 at the Tyrones’ summer home in Connecticut, the film opens with a deceptive veneer of normalcy that quickly crumbles. We meet James Tyrone Sr. (Ralph Richardson), a once-promising Shakespearean actor who sold out for commercial success, his morphine-addicted wife Mary (Katharine Hepburn), and their two sons: the cynical alcoholic Jamie (Jason Robards Jr.) and the aspiring poet Edmund (Dean Stockwell). But as day turns to night, this facade of familial harmony disintegrates.

Triggered by worry over Edmund’s suspected consumption, Mary begins to slip back into her old addictive habits. James Sr. frets over money and property, and his miserliness is a symptom of childhood poverty he can’t shake. Jamie drowns his disappointments in whiskey and cynicism while Edmund grapples with his illness and artistic aspirations. Rather than opening up the play, Lumet leans into its claustrophobic setting. The Tyrone home becomes an arena of simmering tensions, with Boris Kaufman’s black-and-white cinematography growing increasingly shadowy and oppressive as the day continues. Each character is trapped in a cycle of blame and recrimination, unable to break free from old wounds and resentments. Yet underneath their cruelty also lies a desperately aching love. These people wound each other because they care so deeply, their affection twisted by years of disappointment and unmet needs.

10. Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead (2007)

Sidney Lumet’s “Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead” is a searing exploration of the American family in crisis. The plot unfolds like a Greco-Roman tragedy set in the sterile suburbs of New York. Two brothers, Andy (Philip Seymour Hoffman) and Hank Hanson (Ethan Hawke), concoct a plan to rob their parents’ jewelry store. Andy, a successful but secretly struggling payroll executive with a drug habit, manipulates his weaker-willed younger brother Hank into participating. The scheme seems foolproof: no one gets hurt, insurance covers the loss, and they solve their financial woes. But as with all best-laid plans in noir-tinged tales, this one goes horrifically wrong. The brothers’ hired accomplice bungles the robbery, leading to a violent confrontation with the boys’ mother, Nanette (Rosemary Harris).

The fallout from this botched heist spirals outward, engulfing the entire Hanson family in a maelstrom of guilt, recrimination, and violence. Lumet employs a non-linear narrative structure that ratchets up the tension with each reveal. We revisit key events from multiple perspectives, each iteration peeling back another layer of the characters’ motivations and mistakes. Cinematographer Ron Fortunato captures both the sleek, soulless interiors of Andy’s corporate world and the lived-in clutter of suburban homes with equal precision. The color palette shifts subtly as the story progresses, moving from cool blues and greys to increasingly warm, violent reds as the situation spirals out of control. As Lumet’s final film, it serves as a fitting capstone to a career marked by incisive examinations of human nature and morality.

9. The Hill (1965)

Set in a British Army prison camp in North Africa during World War II, “The Hill” is a stark departure from Lumet’s usual urban landscapes while retaining his signature intensity and complex morality. The story centers on five new arrivals at the camp, each facing punishment for various violations. Among them is Joe Roberts (Sean Connery), a former Sergeant Major stripped of his rank for assaulting an officer who ordered a suicidal attack. The camp is ruled with an iron fist by the sadistic Sergeant Major Wilson (Harry Andrews) and his equally brutal staff, including the coldly efficient Williams (Ian Hendry) and the conflicted Harris (Ian Bannen). At the heart of their “rehabilitation” program is the eponymous hill, a human-made monstrosity of sand and rock that prisoners are forced to climb repeatedly under the scorching desert sun.

As the new inmates struggle to survive the grueling conditions, tensions escalate. Roberts, with his military background, becomes a natural leader among the prisoners as he challenges the staff’s authority and refuses to be broken. The screenplay by Ray Rigby (based on his own 1965 play) crackles with tension, each interaction laden with subtext and barely suppressed violence. The dialogue is sharp and often darkly funny, providing moments of gallows humor that only heighten the overall sense of despair. The hill itself becomes a looming presence, always visible, a symbol of the arbitrary and cruel nature of the punishment inflicted on the men.

8. Running on Empty (1988)

Lumet performs a delicate balancing act between a suspenseful thriller and an intimate character study with “Running on Empty,” where the personal and the political intertwine to furnish a deeply moving portrait of a family caught between their principles and their love for each other. The film narrates the tale of the Pope family: parents Arthur (Judd Hirsch) and Annie (Christine Lahti), as well as their children Danny (River Phoenix) and Harry (Jonas Abry). They’re fugitives on the run for the past 15 years after bombing a napalm lab during the Vietnam War. The explosion, intended to be symbolic, accidentally blinded and paralyzed a janitor, turning the Popes into accidental terrorists.

We meet the family as they’re once again uprooting their lives, effortlessly slipping into new identities in a small New Jersey town. It’s a well-oiled routine, but cracks begin to show as Danny, now a talented pianist, faces the prospect of leaving his family behind for a shot at the coveted performing arts school Juilliard. Further complicating matters is his budding romance with Lorna (Martha Plimpton), the daughter of his music teacher, pulling Danny between his loyalty to his family and his desire for a normal life. Lumet manages to locate beauty in the small moments: a family singalong in their car, Danny and Lorna’s tentative first kiss, and the fleeting look of regret on Annie’s face as she watches her son perform. Cinematographer Gerry Fisher favors a muted color palette and unobtrusive camera work, giving the film a naturalistic, almost documentary-like quality that grounds the story in reality.

7. Serpico (1973)

Based on the true story of the eponymous Frank Serpico, this film provides a searing indictment of institutional rot through one man’s relentless fight against systemic corruption in the New York Police Department. Al Pacino delivers a tour de force performance as the titular character, an idealistic young cop who joins the force with dreams of making a difference. We follow Serpico’s journey from wide-eyed rookie to disillusioned whistleblower as he navigates the murky waters of a department steeped in bribery and misconduct. His fellow officers casually pocket payoffs from local criminals, turning a blind eye to illegal activities in exchange for cash. Serpico’s refusal to participate marks him as an outsider, earning him the distrust and eventual hatred of his colleagues.

Pacino’s transformation from clean-cut rookie to bearded, long-haired pariah works on registers both physical and psychological. He conveys Serpico’s growing isolation and paranoia with subtle shifts in body language and piercing, haunted glances. Lumet masterfully immerses us in the grimy, sweltering streets of 1960s and early 70s New York. A scene where Serpico confronts a group of corrupt officers in a locker room is a masterclass in sustained tension, the camera holding steady as the air crackles with barely suppressed violence. The film’s depiction of the “blue wall of silence” – the unwritten code that prevents officers from reporting colleagues’ misconduct – is particularly damning. In an era of increasing scrutiny of police conduct, the film’s themes feel more relevant than ever.

6. The Pawnbroker (1964)

Lumet’s adaptation of Edward Lewis Wallant’s 1961 novel “The Pawnbroker” presents the emotionally charged tale of Sol Nazerman (Rod Steiger), a Jewish pawnbroker operating a shop in East Harlem. Sol is a Holocaust survivor, but to call him “living” would be a gross overstatement. He exists in a state of emotional paralysis. His humanity is calcified by the horrors he endured in the concentration camps. As Sol goes through the motions of his daily life, we’re given glimpses into his past through a series of jarring, fragmented flashbacks. The parallels drawn between the concentration camps and the systemic oppression of 1960s Harlem are provocative and deeply unsettling. In both worlds, human beings are reduced to commodities, and their worth is measured in cold economic terms.

The film builds to a devastating climax as Sol’s carefully constructed emotional walls begin to crumble. A shocking act of violence catalyzes his breakdown, leading to a moment of catharsis that is as painful as it is necessary. Sol’s memories, triggered by seemingly innocuous events, crash into the present with brutal force. Lumet’s innovative use of quick cuts and disorienting camera angles in these sequences is nothing short of revolutionary for its time, viscerally conveying the intrusive nature of the traumatic recall. Sol’s journey is not one of triumphant healing but a painful and incremental crawl toward reconnection with his own humanity, which Lumet underscores by using the claustrophobic confines of the pawnshop as a metaphor for Sol’s psychological prison.

Also Related to Sidney Lumet: 25 Great Trial Films of All Time, Ranked

5. The Verdict (1982)

From the murky waters of medical malpractice to personal redemption, “The Verdict” tells the story of Frank Galvin (Paul Newman), a washed-up alcoholic lawyer who stumbles upon a case that offers him one last shot at professional and personal salvation. Barely scraping by on ambulance-chasing cases, Galvin is handed a seemingly straightforward medical malpractice suit by his friend and mentor, Mickey Morrissey (Jack Warden). A young woman named Deborah Ann Kaye (Susan Benenson) lies in a vegetative state after a botched anesthesia procedure during childbirth at a Catholic hospital. Initially viewing the case as an easy settlement, Galvin experiences a crisis of conscience after visiting the comatose victim. Moved by her condition and the plight of her sister and brother-in-law, he decides to take the case to trial, much to everyone’s dismay.

As Galvin digs deeper, he uncovers a web of corruption and cover-ups involving the hospital, the Archdiocese of Boston, and a prominent medical expert, Dr. Towler (Wesley Addy). The case becomes David versus Goliath as Galvin faces off against a team of high-powered defense attorneys led by the shrewd and ruthless Ed Concannon (James Mason). The film’s visual palette is muted and gloomy, mirroring the moral ambiguity of its characters and the bleak Boston winter. Lumet’s camera work is unobtrusive yet effective, often lingering on faces to capture subtle emotional shifts. Performances across the board are stellar, with Newman delivering one of the finest turns of his career. His Galvin is a man haunted by past failures, and Newman brings a palpable sense of desperation and determination to the role.

4. Fail Safe (1964)

Sidney Lumet’s “Fail Safe,” adapted from Eugene Burdick and Harvey Wheeler’s 1962 novel, is a chilling Cold War thriller that takes viewers straight into a nightmare scenario of accidental nuclear war. When an unidentified flying object appears on the radar of US Air Force planes, a squadron of bombers is sent to their “fail-safe” points – positions from which they’ll proceed to attack the Soviet Union if given the command. Due to a technical malfunction, one group of bombers receives an erroneous order to attack Moscow. As the realization of this error dawns, we watch in mounting horror as military and political leaders scramble to recall the planes or shoot them down.

The action unfolds across three primary locations: the Pentagon’s war room, where General Black (Dan O’Herlihy) and other military leaders grapple with the crisis; the underground bunker of the President (Henry Fonda), who desperately tries to convince the Soviet Premier of America’s mistake; and the cockpit of the lead bomber, piloted by Colonel Grady (Edward Binns), who believes he’s carrying out a legitimate attack. “Fail Safe” explores the terrifying paradox of a defense system so automated that it becomes a threat in itself. Lumet contrasts the calm, methodical actions of the bomber crew and the frantic efforts to stop them to underscore the film’s central irony – that the very systems designed to prevent war could trigger one. The absence of a musical score amplifies the sense of dread by turning the ticking of clocks and the hum of machines into a haunting soundtrack to impending doom.

3. Network (1976)

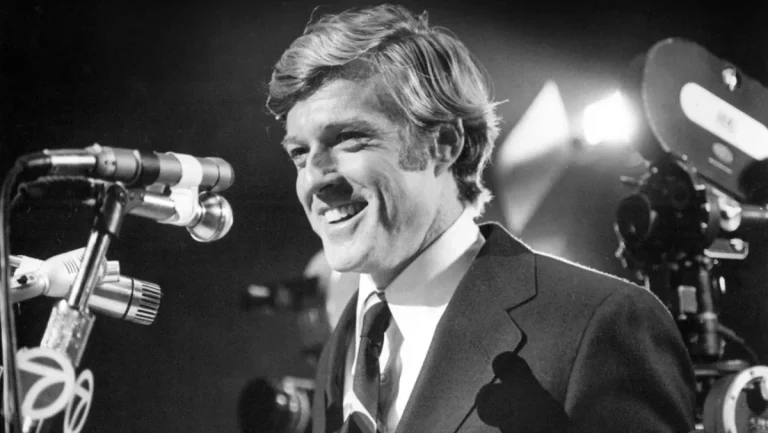

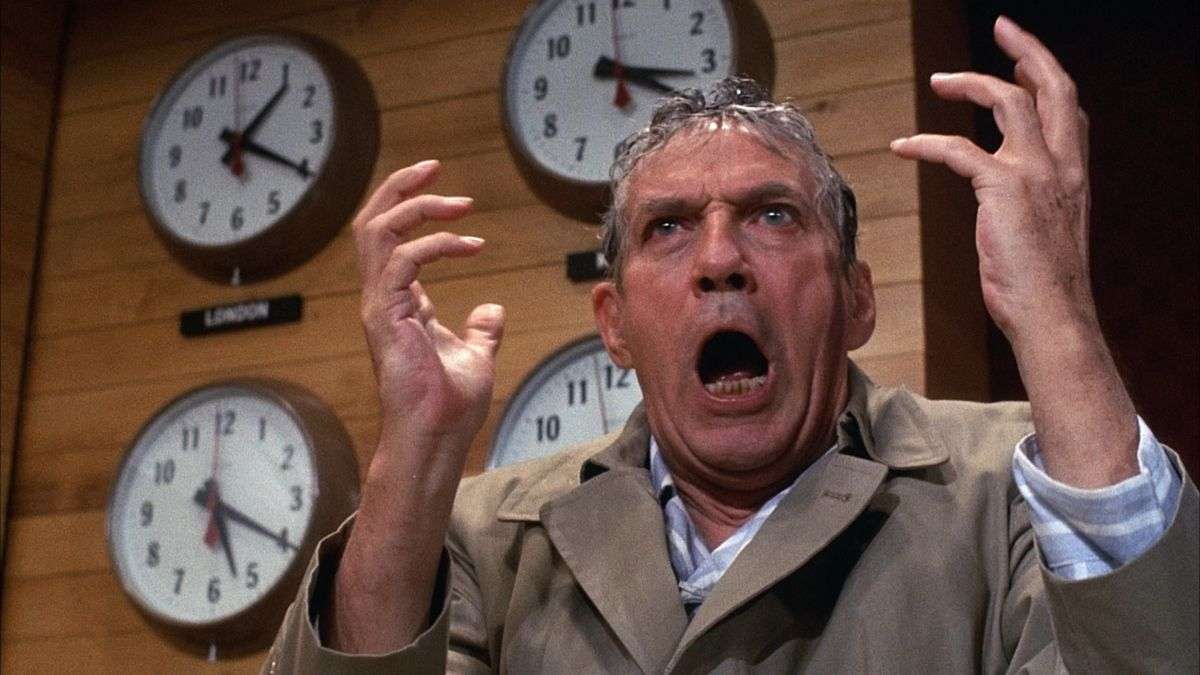

A blistering satire that skewers the world of television with a prescience that’s both hilarious and terrifying, “Network” is Sidney Lumet’s acid-tongued critique of media manipulation and corporate greed that feels less like a cautionary tale and more like a prophecy with each passing year. The film’s plot is a rollercoaster of absurdity grounded in all-too-believable human ambition. We’re introduced to Howard Beale (Peter Finch), a veteran news anchor facing forced retirement due to declining ratings. In a moment of despair, Beale announces on air that he’ll kill himself during his final broadcast. Instead of being immediately fired, Beale’s outburst leads to a ratings spike, catching the eye of ambitious programming executive Diana Christensen (Faye Dunaway).

What follows is a descent into madness – both Beale’s and the network’s. Christensen, with the reluctant help of news division president Max Schumacher (William Holden), transforms Beale into the “mad prophet of the airwaves.” His unhinged rants about the state of the world, punctuated by the now-iconic phrase “I’m as mad as hell, and I’m not gonna take this anymore!” become a national sensation. As Beale’s popularity soars, the line between news and entertainment blurs beyond recognition. Lumet navigates seamlessly between moments of broad comedy, biting satire, and genuine pathos. The film’s visual style evolves as it progresses, mirroring television’s transformation from the staid, serious news division to the garish and sensationalized “Howard Beale Show.” Beale’s transformation from suicidal anchor to messianic figure to corporate puppet stands as a potent metaphor for the evolution of television.

2. Dog Day Afternoon (1975)

Transforming a botched bank robbery into a gripping exploration of media spectacle, sexual identity, and the American Dream gone awry, “Dog Day Afternoon” crackles with an electric energy that feels as immediate and relevant today as it did nearly five decades ago. On a scorching August day in Brooklyn, Sonny Wortzik (Al Pacino) and Sal Naturale (John Cazale) attempt to rob a bank. Their plan quickly unravels, devolving into a hostage situation that captures the attention of the entire city. As police surround the bank and crowds gather, we learn that Sonny’s motivations are far from simple greed – he needs money for his partner Leon’s (Chris Sarandon) gender reassignment surgery.

Sonny, a Vietnam veteran with a knack for working the crowd, becomes an unlikely folk hero. He shouts, “Attica! Attica!” – referencing the recent prison riot – turning bystanders against the police. Inside the bank, Sonny forms a peculiar bond with head teller Sylvia (Penelope Allen), revealing layers of his complex personality. Lumet employs handheld camera work and long takes to create a documentary-like realism that pulls viewers into the heart of the action. The film’s pacing mirrors the ebb and flow of the standoff – moments of high tension are interspersed with quieter, character-driven scenes that deepen our understanding of the players involved. Sonny becomes a reluctant celebrity, and his personal drama plays out on live television. The film critiques the media’s ability to transform tragedy into entertainment, presaging our current era of 24/7 news cycles and viral sensations.

1. 12 Angry Men (1957)

Sidney Lumet’s directorial debut “12 Angry Men” is also his magnum opus: a taut courtroom drama set almost entirely within the claustrophobic confines of a jury room, presenting a fierce examination of the American justice system, prejudice, and the nature of reasonable doubt. The film opens “on the hottest day of the year” as twelve jurors file into a small sweltering room to decide the fate of an 18-year-old defendant accused of murdering his father. What seems at first to be an open-and-shut case, when eleven jurors vote guilty in the initial poll, becomes a grueling battle of wills and wits when Juror 8 (Henry Fonda) casts the sole “not guilty” vote. What follows is a meticulous deconstruction of the case and, more importantly, the jurors themselves.

As Juror 8 methodically questions the evidence and testimony, we watch the veneer of certainty crack, revealing the prejudices, personal baggage, and flawed reasoning underlying the other jurors’ rush to judgment. Lumet’s direction shines in his ability to wring maximum drama from minimal elements. As tensions rise, Lumet gradually lowers the camera and uses increasingly tighter shots, creating a palpable sense of confinement and pressure. The effect is so subtle that viewers feel the walls closing in without quite knowing why. In just 96 minutes, Lumet and screenwriter Reginald Rose create twelve distinct characters, each with their own motivations and arcs. The gradual reversal of votes becomes a character study in miniature, each change revealing something about the juror in question.