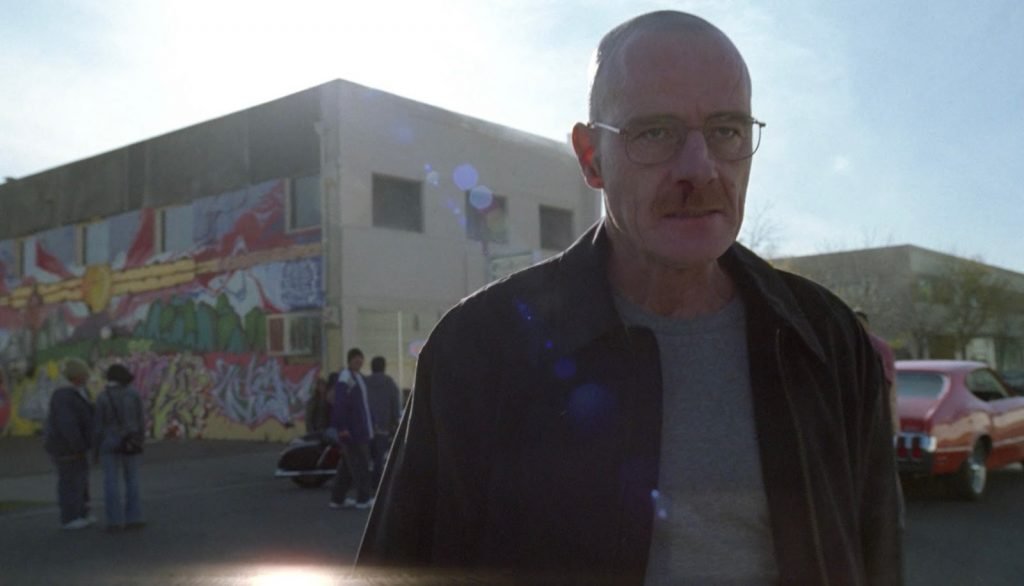

Perhaps one of – if not the – most famous television anti-heroes of all time is Walter White, the protagonist of AMC show Breaking Bad, 2008-2013. Created by Vince Gilligan, Breaking Bad follows Bryan Cranston as Walter White – a high-school chemistry teacher who begins cooking meth as a means of “providing for his family”. When Walter finds out that he has lung cancer, he acquires the help of ex-student junkie Jesse Pinkman, partnering up in a makeshift RV lab to cook in the New Mexican outback. What starts as a quick-cash scheme to help Walt’s family after he dies soon turns into a wake-up-call, showing Walt that his mid-life crisis can be remedied by the life of crime (which he coincidently discovers a knack for).

From the hugely successful “Pilot” episode, Breaking Bad went on to make five seasons, a movie (El Camino, 2019) and a spin-off series (Better Call Saul) due to air its sixth season in 2021. Walter White and Jesse Pinkman are now an iconic duo of mainstream television, but there’s a whole host of reasons for Gilligan’s success, from the outlandish (yet brilliant) storyline to the clever use of cinematography. The one reason that stands out the most, however, is its protagonist: the intelligent, manipulative, greedy, and often laughable Walter White. Let’s take a look at why (spoilers ahead):

From the very title Breaking Bad, Walt’s character development is already set in motion. As even first-time audiences can gather, there will be a point in the show when our protagonist goes from “good” (although Walt is arguably never truly “good”, but for now let’s assume he is) to “bad”. “Good” being a lawful, moral family-man who contributes to society as a teacher, and “bad” a pathologically-lying drug lord, responsible for multiple deaths. But this switch doesn’t happen over-night. It takes five seasons of character building to navigate Walt’s journey from A to B – and you’re in for a bumpy (and thoroughly entertaining) ride. Believe it or not, the plot of the pilot pretty much summaries the entire show, foreshadowing (a common tool used by Gilligan) Walt’s rise and ultimate downfall.

The Pilot

“It is growth, then decay, then transformation” is Walt’s explanation for Chemistry in episode one. It’s fitting that he should devote his life to science that very much mirrors his character: Walt grows his status as a criminal, manifesting his own alter-ego identity in the name of Heisenberg, before his health and family life decays, transforming him from weak-willed average joe to New Mexico’s most wanted.

Must-Read: Five Screenwriting Lessons You Can Learn From Breaking Bad’s Pilot

As a microcosm of the entire show, “Pilot” introduces Walt frantically confessing his crimes on tape, pleading “I only had you in my heart” to his family and subsequently planting the motive that pushes Walt throughout the 62 episodes. He is an awkward man of few words, to begin with, dressed entirely in beige and working a second job cleaning cars.

About forty minutes in, Walter “breaks bad” by beating up some bullies in a clothes store. He recruits and begins cooking with Jesse; things go well at first, but of course, chaos soon erupts. By the end, Walter impulsively tries to commit suicide to escape getting caught but the gun is empty. The rise and fall of Mr. White – his complicated relationship with Jesse and aversion towards his home life (though he incessantly claims they are his priority – perhaps to try and convince himself of the lie?) – are all mapped out in the structure of the very first episode.

Pinpointing when Walt “Broke Bad”

There are arguably multiple points where you could declare Walter as “Breaking Bad”; that exact moment wherein he crossed the threshold from Walter White to Heisenberg. The first would be in the pilot – as mentioned above – or perhaps it was a little later on, when killing Krazy-8 (after much hesitation yet, interestingly, with a brutal garrotte method). Or perhaps simply when he first shaved his head? It’s hard to pinpoint exactly when Walter “transformed”, mostly because there are still always traces of both sides in him – beginning to end.

Despite beginning the show as insecure and disrespected, Walter still exhibits his sociopathic tendencies right from season one. Though subtler, Walter’s nature has always been blunt and somewhat cold, rarely seen laughing and constantly begrudged. There is an air of snobbery about Walt – disgusted by the unprofessionalism of his doctor over a small stain on his shirt, even when still the polite family man.

Things start to turn around when he challenges his brother-in-law (and DEA agent) Hank at a family celebration. Not only does Walter assert his authority here – a trait he decidedly lacked beforehand – but the petty act verges on cruelty, allowing his villainous counter-identity to bleed into his family life. What’s interesting is that this crossover occurs over a matter between Walt and Hank not because it’s criminal versus law enforcement, but over his son, Walter Junior.

Junior (or “Flynn”, as he’s later called) clearly looks up to his uncle more than his father. Whereas Walt was at first too meek to stop it, Heisenberg is confident enough to win back his son’s respect. Having celebration drinks in the garden, Walt pours his 16-year-old son a few too many than he should, which Hank questions. Flynn looks to Hank, and for the first time Walt sternly demands attention back as the alpha male – “What you looking at him for?”

Walt continues to pour until Hank holds his hand out over the cup – alarmed now by Walt’s uncharacteristic behaviour – but Walt lets the booze run over his hands. He shouts at Hank to bring the bottle back, exposing the drama to the whole party. However, Walt’s want for respect has extended into greed for power, desperate to prove himself to his pitying family. As a result, Flynn throws up in the swimming pool, making him the victim of his father’s actions (as he will be many times to come).

Inversely, there are still traits of Walter’s old, timid self even during his peak Heisenberg days. Though in the drug business Walter’s status has gone up, this identity must be concealed at all cost. Walter White is still bound by certain social rules and responsibilities at home, and to tread too hard in other aspects of life could alert suspicions as to who he really his. He is forced into treatment, interviews and receiving “charity” against his will, caught between wanting to assert authority as head of the household and keeping his feared counter-identity on the down low. It’s not necessarily the fact Walt must keep his new career (and persona) a secret that is the obstacle, but his own arrogance that subconsciously wants them to know that is the real challenge.

Walt doesn’t want to be seen as a charity case, but he must allow it as it gives him a source to launder money through. If he did not possess so much hubris – a common feature of the anti-hero – Walt would execute a double-life much more easily. However, when Gale is made the lead suspect as the infamous Heisenberg, Walt can’t resist boasting that Gale isn’t smart enough to pull off a 99.1% purity in crystal meth – “Genius? Not so much.” A little drunk off wine at one of the many intense dinner scenes of Breaking Bad, Walter is prepared to risk exposure simply because he can’t bear somebody else taking all the credit. “All his brilliance looks like nothing more than just simple rote copying” he theorises, thus reopening the DEA case that’s been lingering dangerously over his head for so long. Not only has he broken bad, but he seals his fate to die over it. Getting killed by his own bullet is metaphorically fitting.

The Fatal Flaw

Like the protagonist of a Shakespearean tragedy, Walter White has the ability to achieve greatness, but fails at the hands of his own behaviour. Walt has all the makings of a criminal mastermind: the intellect and determination; a disregard for certain morals and a talent for manipulation. Unfortunately for him, Walter is also excessively prideful, arrogant and greedy. To find out where these characteristics stem from – and why they are so dire for him – we must first look at his motivations:

Despite his constant babbling that everything he does is for his family, everybody – whether that be the other characters or us, the viewers – can see this is a lie. Walt’s beige existence is symbolised by a change of wardrobe – from bland chinos and reading glasses to red shirts and black sunglasses – and driven by his need to break free. “There’s more than one kind of prison” he says to Jesse, waiting for Jimmy ‘In and Out’ to get incarcerated on his behalf. Is this prison his home life? Walt’s outward reality of working two boring jobs, never able to live out his dream of being a hailed genius?

Albeit we rarely get any backstory to Walter’s childhood, he does tell a revealing story of his father to Jesse, gaining us some insight as to why it’s so important that he must “Live Free or Die” (as it says on Walt’s number plate and the title for season five, episode one). Mr. White describes his father as an empty rattling can, “like there was nothing in him”. Witnessing this kind of hollow lifestyle obviously triggered fear in Walt – one that, when he realises that he has come to live too, he must “break” from.

In season three, we are reminded of Walt’s prior way of life through a flashback to the pilot. When Jesse calls his old teacher out for suddenly acting out – “Some straight like you, giant stick up his ass, all of a sudden aged what – sixty? – he’s just gonna break bad?” – all Walter replies is “I am awake.” Compared to Walter’s usual stern (or frantic, rarely ever in-between) demeanour, he says this revelation with clarity, as if he’s just had an epiphany. Being “awake” or “free” is made crucial for Walt right from the first episode, later analogized into rust building upon a car as a metaphor for his own wasted genius. Parallel to Walter’s character evolution is the growth of this motivation. At first, it’s understandable. But this midlife crisis soon grows into something much greedier and sinister: an insatiable lust for power.

Now that Walter’s lack of fulfillment has propelled him into crime, it’s time for him to rise (and fall). A double-edged sword, greed is what allows Walt to climb the ladder – driven to always think bigger, purer, richer – but it also makes him unable to reach the top. Early on, when Walt decides to risk his life meeting cartel kingpin Tuco for more cash, Jesse asks “why can’t you just be satisfied with the way it is?”. It’s this question that haunts Walt throughout the entire narrative – a question he refuses to answer or face-up to outright, probably because he knows, deep down, he will never be satisfied.

Another fatal flaw of our modern-day folk hero is his arrogance. Though Walter is undoubtedly a smart man (co-founder of a billion-dollar company and creator of the most chemically pure methamphetamine around) he can oftentimes overestimate his abilities. Walt thinks he can read his own diagnostic from glancing an x-ray, without any medical training, convinced his cancer has worsened when in fact it has shrunk.

Now that he’s top-dog in the eyes of the DEA, Walt’s head gets a little too big for his hat, looking down on everyone in the stubborn belief he’s always right. A great example of Walt’s inner arrogance – set free by the manifestation of his ego, Heisenberg – and how it prevents his success, is in the pre-credit sequence of season three, episode two:

Walter is pulled over by a cop because of his shattered windshield. At first, he is compliant, as his original, law-abiding self would be. However, Walter’s superiority complex soon gets the better of him when he shifts into his Heisenberg persona (another symbolic microcosm of his character arc). Automatically Walt begins demanding authority, insisting “no, no, no – you listen to me. It’s time for you to listen to me.” Of course, Walter White has no real power against law enforcement, and, blinded by his arrogance, he is arrested. (Ironic, considering he’s got $80 million in drug money being laundered, yet it’s the windshield that gets him in trouble).

A similar scenario occurs when Walter tries to kiss Carmen – the assistant principle of the school he works at. So used to getting his own way as Heisenberg, he expects her to oblige. Instead, Walter gets placed on leave. Walt’s egotistical nature really begins to show around the midpoint of the show when Walter buys a flashy new car with the drug money his wife so tirelessly nags him to conceal. A strangely impulsive move for an intelligent man – surely, he knows this would alert suspicion? Despite what he says, perhaps Walt wants to get caught. Perhaps he’d prefer fame over freedom. Or perhaps he’s just looking for an escape…

Is Walter White Suicidal?

There is something alarmingly nonchalant about Walter’s approach to crime. Although he is, at first, undoubtedly hellbent on keeping his new career a secret, this remains his primary concern. When on the field, Walter takes increasing risks as times goes on, seeing these dangers only as a threat to his exposure rather than on his life. His wife, Skyler, is far more upset about Walt’s cancer than he is. Perhaps this is an advantage on Walter’s part? Being unafraid, to a certain extent, of death allows Walter to enter dangerous situations with an upper hand.

Recommended Read: The Weaker Sex in Breaking Bad

In season two, Water finds out his tumour has shrunk by 80% and has to hide his disappointment from his family. He constantly refuses treatment and pushes himself, physically, to the limit when cooking meth, despite his body needing rest. In the “Fly” episode of season three, Walter admits to Jesse in a rare display of emotion that the “perfect time” to die “passed me right by.” Walter pinpoints the exact moment he should have died – once he’d made money for his family and lived life on the edge, but before things got out of hand – “I’m saying…I’ve lived too long”.

Though it may to be Walter’s advantage in his line of work, his dismissal for his health verges on being suicidal (after all, he does try to shoot himself in the very first episode) – even after he’s “broken bad”. The number plate “Live Free or Die” perhaps holds some deeper meaning here; maybe Walt never truly feels “free” so long as he’s stuck in an unhappy marriage, working a job he doesn’t like or need and continually wearing the mask of Walter White. Perhaps his only option is to die. At least as Heisenberg he can go out with a bang.

From Walter White to Heisenberg

For a large part of the story, Walter is made to juggle his two identities, switching between Mr. White and Heisenberg depending on the situation. Before this, he was simply Walter, and afterwards, he is left only with Heisenberg. But at what point does Walt ditch his former life and becoming wholly encompassed by the drug industry? Not so much when he “broke bad” – as we’ve already discussed – but when he stayed bad.

Heisenberg creeps slowly into Walter’s normal life around season two. When a student asks him to raise his grades, his face drops into the stern, blank expression he uses when talking to the cartel, telling him “don’t bullshit a bullshitter”. Here, we see the confidence of Walt’s new-self running into his everyday career as a high-school teacher. Towards the end of the season, Walter wears his meth-cooking suit when cleaning out the rot in his house, physically bringing Heisenberg into his home for the first time which he so incessantly claims to keep separate.

This image recurs later in season four. Albeit without the space suit, Walter is again shown scrabbling underneath the floorboards where the rot was. Literally entitled “Crawl Space”, in this episode Walter plans to use the money stashed under the floor to buy a new identity – his family’s life in severe danger, as well as his own. However, Skyler has already spent the money, practically securing his (and Hank’s) execution. The use of frame-within-a-frame here has the symbolic resemblance of a grave, which Walt begins to weep in. We feel sympathy for out protagonist for only a moment, before his cries morph into the manic laughter of a villain. Skyler is horrified by her husband’s cackling, looking down on a man she no longer recognises – looking down at Heisenberg. Buried beneath the floor, Walt’s death is foreshadowed, doomed to be a dead-man walking.

Back in season two, when it comes to choosing between his daughter’s birth and meeting Gus Fring (cartel kingpin) – essentially, choosing between his old and new life; Mr. White or Heisenberg – he chooses Gus. Heisenberg is no longer in the passenger seat, but driving the car. Eventually he is kicked out of the house and lives in his own apartment, alone and free to cook without all the lies. He is now Heisenberg. But, of course, this still isn’t enough for Walter White.

Jesse Pinkman: Walter White’s One Moral Redemption?

Walter White’s redeeming qualities are few and far between. But there are a handful of scenes that exempt Walt from being an outright villain. Nine times out of ten, these scenes occur with Jesse – his relationship with Walt being the basis of the entire show. Their friendship (which often entails trying to kill each other) has become as much of a cultural emblem as Walter White himself.

What makes Walt and Jesse such a good team is the fact they’re polar opposites – they balance each other out and make-up for what the other one lacks. On a very basic level, Walt knows the chemistry and Jesse knows the streets. However, there are clear parallels drawn between the two from very early on, which unites them beyond simply having the common goal of a healthy paycheque. In season one they are both shown smashing their phones up after an argument, both muttering “son of a bitch” to themselves as an example of their shared attitudes in life. Their methods are different but their goals are the same; Walter ensures the logical side of their business is kept, whilst Jesse’s moral-compass prevents Walt getting too carried away with being the bad guy.

Walt and Jesse’s relationship can be read in a number of ways: mentor and student; the cook and the distributor; the father and the son. In conjunction with Walter’s established lust for intellect and superiority, he is naturally inclined to “teach” whoever he is with, which can often be conceived as criticism. Not only is he a teacher in the classroom, but feels compelled even to advise strangers on where to buy chemistry supplies without alerting the DEA.

This complex matches their partnership perfectly, with Jesse even being an ex-student of Walt’s. Jesse is naïve and slapdash with his cooking, so Walt takes it upon himself to be the mentor – something he takes great joy from. Walt teaches Jesse how to cook the perfect batch of meth, make a car battery and manage his unreliable “co-workers” Badger and Skinny Pete. Walt’s hot temper and Jesse’s angst causes many of these lessons to end in fights, resultant of Walt’s constant critiquing. However, it can also create a wholesome foundation for success, redeeming Walt’s failings in some small way.

The father/son dynamic is subtler, but just as important as being the mentor. It’s visible that Walt connects to Jesse more than he does to his own son, who on the whole finds his father embarrassing and awkward. Although Walt and Jesse spend half of their on-screen time squabbling, they also give each other the praise and advice they miss out on from their own father/son. “You’re good at a lot of things, son” Walter reassures Jesse, fresh out of rehab. This line is particularly enlightening because the phrase “son” is not part of Walter’s usual lexis, perhaps signifying something deeper in their love/hate relationship. Afterall, Walt does introduce Jesse as his ‘nephew’ to suspecting outsiders (rather than just a friend), considering his old student part of the family.

Walter practises a socially-acceptable level of investment in his real family, caring for their needs in a very superficial way. By the end of Breaking Bad, Walt has manipulated Skyler into an almost abusive marriage which she struggles to get out of. Jesse is arguably the only person Walter truly cares for, rescuing him from a crack-house when Jesse falls into relapse. When their lawyer Saul Goodman suggests killing Jesse in season five, episode twelve (a common solution for Walt), he gravely threatens not to “float that idea again.” Jesse seems to be the only exception to Walt brutal wrath – but it’s a little more complicated than that.

Jesse is the moral grounding in his and Walt business partnership, which often makes him an obstacle to Walt’s goals. Though society would stereotypically assume Jesse to be the junkie-criminal and Walt the respectable family-man, it’s in fact Jesse who cries over an incident involving Walt’s favourite poison – ricin. Whilst Jesse sobs over the ‘death’ of Brock Cantillo, Walt rolls his eyes, embodying their typical moral stance. However, Walt does this as he hugs Jesse, providing him with comfort despite thinking it a little dramatic. On the rare occasion Walt himself gets emotional, it’s only Jesse that witnesses it – for example, putting Walt to bed after admitting he should have died months ago.

It’s not always clear-cut whether Walter is really redeemed by his friendship with Jesse. When he withholds Jesse’s money from him to ‘stay sober’, it could be interpreted that this is for Jesse’s own good or that Walt simply requires an efficient workforce. Walter assures Gus that Jesse is an asset because “He does what I ask. I can trust him.” Does Walt really only want Jesse alive for guaranteed authority? When Jesse is replaced by Gale as the perfect lab-partner – smart, compliant, organised – Walt does nothing but complain. Is it because Walt’s no longer the only genius in the room? Or because he genuinely misses Jesse as a partner, son and friend?

Of course, the biggest spanner in the works for Walt is Jane Margolis – Jesse’s girlfriend. When Walter watches Jane die of a heroin overdose, he does nothing to help her. Walter reasons that her death will teach Jesse the ultimate lesson to stay sober – but how morally corrupt can one go just to teach a lesson? Though Walt weeps at the sight of Jane’s death (his emotional response preventing him from being an outright sociopath) he nonetheless allows it, even boasting to Jesse that “I watched her die” in a vengeful outburst of hate. But was it really all to keep Jesse – his one source of true friendship – alive and healthy? I suppose that’s down to the viewers to decide.