And the man shoots himself in the end. But how did we get here? Well, that’s a story, a long one. Long enough to transcend centuries. You see, some movies don’t last 3 hours; they last decades. Staying relevant year after year, across generations. I read somewhere that sometimes generations need to think about what’s already been thought out, that’s the flow of time. Populations remember a lot of things, but sometimes ideas do get lost with the passing of time. Movies like Kieslowski’s “Camera Buff” are not only relevant for their craft but also act as a reminder that our forefathers have also contemplated similar issues before we were here.

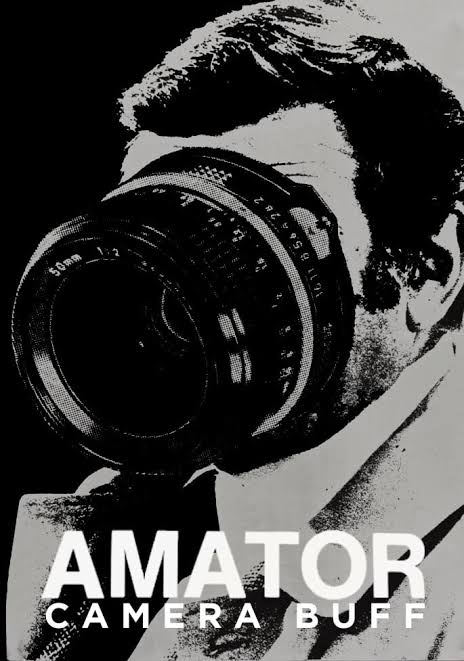

The story is set in the People’s Republic of Poland of the 1970s, where cameras are not only rare but also cumbersome and expensive. Editing is not a hobby; it’s a chore. A well-intentioned factory worker, named Filip Mosz, buys a camera to record the early life of his daughter, but what could go wrong? Well, a lot. The movie is called “Amator” in Polish (tr. “Amateur”). While the word has different connotations today, it comes from the same root word as “mate” (to love). The French word ‘Amateur’ means “one who loves, lover,” and that’s what Mosz is. A lover of the camera, a lover of family, and a lover of life.

Among other requests, Filip gets a request from his neighbour Piotrek, a hearse driver, to record him and his mother. Soon, the mother has to be rushed to the hospital in the same hearse. Later, the local Communist Party boss asks him to film a jubilee celebration event of his plant, which plants the seeds of obsession inside Mosz. This obsession is what drove Mosz then, and our society today, towards questionable decisions and unstable situations.

With a godlike power to record all that he sees, he soon becomes obsessed with the act of recording. He records what he sees, or rather what he wants to see. From recording factory top management going to the loo, to his daughter crying. He records it all in its crudest form, sometimes organically, sometimes human-made (managers going to the loo was the organic one). But there’s another layer to this – censorship. His boss clips the feather of the dove and asks him to cut out the scenes of pigeons flying and management going to the urinal; for men in power don’t want to be seen doing menial tasks, and they definitely don’t want to watch doves flying.

Even this early, we see the voyeuristic nature of Filip and his camera. Maybe the camera and the human that wields it, both are inherently voyeuristic*. Recently, in a piece of miserable news, we saw the presence of a Bangalore-based Instagram page that shared pictures of women in the metro, clicked without any consent.

As deplorable as this is, I wonder if voyeurism is an inherent feature of society today. With cameras fluttering like houseflies, we capture images everywhere. These images become inherently intrusive when they expand their territory from nature or buildings to humans. Voyeurism is widespread. Recording fights in metros to capturing young boys playing.

When we click “wholesome and romantic” pictures of a couple, usually from the lower stratum of society, holding hands, do we take their consent? Or when we record videos of a poor boy hugging his hungry sister, do we ask them? Or does the right to privacy vanish when you don’t live in gated societies?

Related Read: All Krzysztof Kieślowski Feature Films, Ranked

And it’s not just the visual voyeurism but also cerebral. Recently, during the Pakistan conflict, X was filled with “minute-by-minute” updates of drone attacks and ceasefire violations, mostly watched and liked by people living far from such areas in peaceful air-conditioned homes.

While staying updated is good, how many of us spend time actually understanding conflicts or the two countries? And then there’s political news, we spend time reading random statements by politicians and seeing who’s ahead in elections, but not on policy papers. I call this parliamentary voyeurism. And new age media feeds on this temptation, the temptation that spicy news is just around the corner, just one reload away; and once I see it, I will share it… first. From the Prince Borewell case to modern football transfer market updates, voyeurism is widespread.

Call it obsession or voyeurism, with the help of a beautiful panellist and a fellow amateur, Anna Wlodarczyk, Filip’s film reaches an amateur film festival. When he’s on the train towards the festival, Irka, his wife, shouts: “Don’t win”. But Filip can’t hear her. Using the noise of the train as a metaphor, Kieslowski shows us that Filip is too full of himself, too full to hear his wife’s cry and his daughter’s crying.

To Irka’s misfortune, Filip wins the third prize, 4000 zlotys, a film diploma (which he later gives away to his boss as it is of no use to him), and a date with Anna. Effectively second as the panel deems no film good enough for the first. When one panellist exclaims: “…My fellow jurors talk very eloquently about the movies. They talk of ‘social commitment’, ‘modern narrative’, and ‘documentation of times.’ But I saw nothing of the sort. These films were all terrible. They reveal a knowledge of life drawn from TV and newsreels, not from personal experience. It is the duty of television to broadcast certain things. Amateurs have no such duty. You can do what you like, when you like, and how you like. That’s where your strength lies…” Acclimatising the viewers with concepts like cinematic gaze and the role of amateurs.

As you can imagine, things go south between Filip & Irka after this. While Filip starts working on his new project, the life story of an old dwarf factory worker, Wawrzyniec, his personal life goes for a toss. Things don’t work out with Irka, and the affair with Anna always had the lifespan of a fruit fly. The dwarf documentary got local acclaim and was even aired on television. During the recording, Filip meets Krzysztof Zanussi, playing himself. While others accuse Filip of making a joke of the dwarf, Zanussi could see through the craft and appreciate it. During the TV screening, Filip is with Wawrzyniec, and the movie is successful in making him cry.

Filip’s third movie was an exposé of the misallocation of funds for town renovation. And this is where he starts facing the perils of passion. Five months pregnant, Irka has already moved out with her baby, and we see Filip’s regret during a scene at 1:32:00 where his editor and partner Witek tells him that Filip’s baby is cute and Filip has to instantly look away in regret, thinking about the decisions he has made.

Later, his boss reveals to Filip that as a result of his exposé, Stasio Osuch, the head of the works council and Filip’s dear mentor, will lose his job, and work on the new nursery school will have to be stopped. This breaks Filip down to his core, so much that Filip retreives the canister for his as-yet undeveloped expose film about the brickyard, which he has learned is not operating due to lack of materials, with the workers being secretly employed on other town projects, opens it and tosses the film out to be exposed to the light.

Meanwhile, in a scene, the movie subtly discusses the relation between art and politics, when Filip goes to a shop and buys two magazines: Film and Polityka. Politics, art, and cameras have an interesting intersection: surveillance, aka voyeurism by the powerful. From Banksy’s “One Nation under CCTV” (2007) to “Cameraheads of Skibidi Toilet”** (2024), surveillance art has always been relevant since cameras have spread wide and far.

Technology has been used and will be used to control and drive the masses; rebellions will be quelled, and agitations will be quashed. The coverage of contemporary camera technology turns citizens into perpetual prey of the Panopticon effect. There’s nothing that pleases the powerful more than self-censorship. This head of the voyeurism dragon is the most dangerous one, for it not only breathes fire, but it makes you believe living in fire is the norm. Voyeurism is widespread, and surveillance is suffocating.

But it’s not all doom and gloom with technology. One of my friends really likes photos because she wants to capture the moment before it slips away. Her emotions, best summarized in this quote by Jodi Picoult: “This is what I like about photographs. They’re proof that once, even if just for a heartbeat, everything was perfect”. It’s depicted in how Piotrek, after his mother’s demise, looks at the video made by Filip and says, “A person is dead, but she lives on here, that’s beautiful”.

All we need to do is look inwards, before it gets too late, and before our world turns upside down. We need to leave the obsession with the hearse before it becomes the vehicle of the last journey for our loved ones, and we are not able to gather the courage to attend their last rites. Roman poet Juvenal once asked, “Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?”, or better known as “Who watches the Watchmen?” as also asked by Alan Moore. Today I ask – Who records the Recorders? Let’s turn our cameras towards ourselves, like Filip Mosz did. Let’s shoot ourselves, like the man shoots himself in the end.

Fin.

*Society has accepted the use of the term voyeur as a description of anyone who views the intimate lives of others, even outside of a sexual context. This term is specifically used regarding reality television and other media that allow people to view the personal lives of others. This is a reversal from the historical perspective, moving from a term which describes a specific population in detail, to one which describes the general population vaguely. (Wikipedia for Voyeurism)

**A great analysis on Skibidi Toilet, machines, camera gaze & surveillance in this video by Aidan Walker (https://youtu.be/4qmT05ILtAs?feature=shared)