The Top 55 Japanese Movies of the New Millennium: It is generally believed that Japanese cinema’s downfall started in the 1980s, and the 90s economic stagnation knocked the film industry down until its revival of sorts through J-horror (in the late 1990s). But since cinema history is often written from a Western perspective, we need to deeply examine such a one-dimensional outlook directed against any home-grown national cinema. It’s true that the spread of television reduced the number of theater-going audiences in Japan in the 1970s and 1980s.

At the same time, Hollywood movies garnered more popularity than Japanese ones. Moreover, the biggest Japanese film studios like Shochiku, Toho, and Nikkatsu were in deep financial trouble from the start of the 1970s, and they hardly made the kind of movies that found an international audience. Finally, we should take into account the fact that around the 1980s & 1990s, Mainland Chinese, Hong Kong, and Taiwanese cinema became the face of Asian cinema in the European and American markets.

But it doesn’t mean there was a dearth of new talents in the post-new wave generation Japanese cinema. From Kazhuhiko Hasegawa’s “The Man Who Stole the Sun” (1979), Kohei Oguri’s “Muddy River” (1981), Yoshimitsu Morita’s “The Family Game” (1983) to Juzo Itami’s “The Funeral” (1984) & “Tampopo” (1985), and Mitsuo Yanagimachi’s “Fire Festival” (1985), we are gradually discovering the gems of Japanese cinema from this era. One of the great Japanese auteurs, Nobuhiko Obayashi, made some of his best works in the 1980s. And who can forget the rise of anime and the domination of Studio Ghibli in the 1980s & 1990s? Then, there was Takeshi Kitano, Shinya Tsukamoto, Kiyoshi Kurosawa, Hirokazu Koreeda, Naomi Kawase, and so on. Even veteran Japanese filmmakers like Nagisa Oshima, Shohei Imamura, Kaneto Shindo, Masahiro Shinoda, Seijun Suzuki, and Koji Wakamatsu were making movies in the 80s, 90s, and some even in the 2000s.

The point is that – despite the limited output of the massive Japanese movie industry in the decades following the 1960s or the alleged lack of creative flourish – Japanese cinema always continues to be one of the greatest cinemas around the globe. The masters of 21st-century Japanese cinema are also engaged in the process of comforting the disturbed and disturbing the comforted. Maybe our myopic tendencies might have kept some of the gems of modern Japanese cinema hidden. It’s akin to what the Nigerian author Adichie says about ‘the danger of a single story.’ A phrase she uses in her TED speech to emphasize how false perceptions and overly simplistic beliefs can restrict our ideas about a person, a group, or a country.

In that way, movie lists are efficient in overcoming the simplistic notions about national cinema. A movie list, of course, is strictly subjective, and hence, it’s not definitive, even though the title makes it sound like that. In fact, making a movie list is not an act of educating movie lovers. But it’s also an act of learning and sharing. So join us in this process, and let’s look at some of the best movies of Japanese cinema from the ongoing 21st century:

1. Audition (2000)

Takashi Miike’s adaptation of Ryu Murakami’s 1997 novel was made in 1999. It was adapted for the screen by Daisuke Tengan (son of Shohei Imamura). But it was released in Japan in March 2000 and even entered into a few festivals in early 2000. Moreover, the film was beset with many distribution problems. Hence, that’s reason enough to include one of my favorite Miike films in this list. Though Takashi Miike started making films in 1995 (“Shinjuku Triad Society”), “Audition” was the film that brought him global attention. The film was considered an important work of J-horror – horror fiction based on Japanese popular culture that’s totally different from Western culture’s take on horror. But even within the J-horror framework, “Audition” is a strangely fascinating psychosexual cinema that offers an examination of womanhood that confirms as well as disrupts patriarchal expectations.

The narrative begins in a very low-key manner. Aoyama, a 40-something widower, lives peacefully with his 17-year-old son Shigehiko. Aoyama uses an audition for a film project as the false front to search for a potential life partner. One woman stands out in the audition: the beautiful and elegant Asami. But soon, the deceptively gentle drama takes unexpected turns and delivers a huge blow to our senses.

2. Eureka (2000)

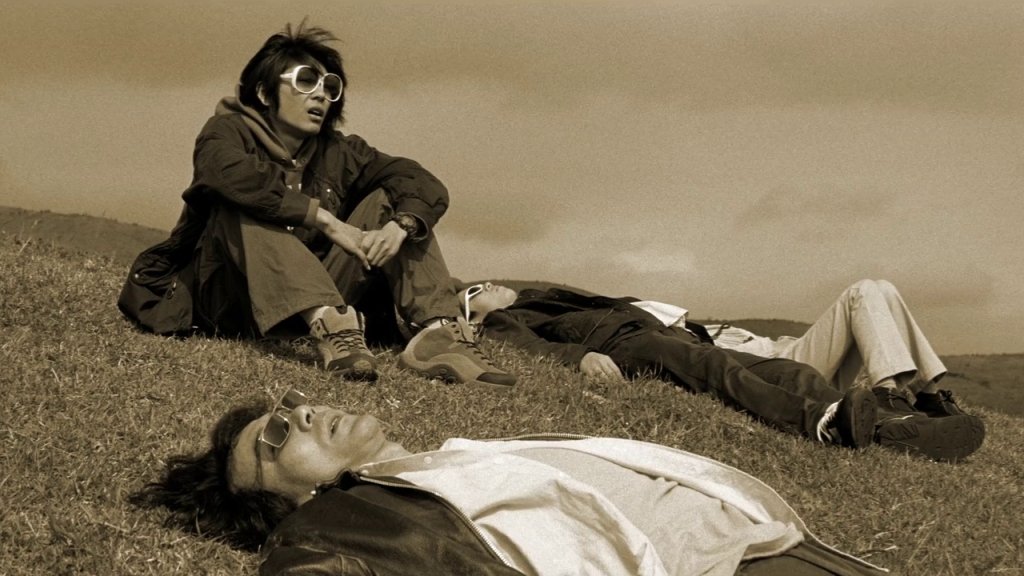

Shinji Aoyama’s de-saturated 217-minute film is an intimate study of trauma, the after-effects of violence, and the tough healing journey. The three central characters are the survivors of a violent bus jack. “Eureka” demands our patience and keen focus since the expression of trauma is so subtle and lifelike. The wordless glances, the inability to resonate with the outside world, the disorientation, and everything that defines the lingering nature of trauma are so painfully portrayed. Aoyama delves into emotional truths that are rarely contemplated on-screen.

However, “Eureka” isn’t simply filled with stark and vast landscapes, subtle gestures, and uncomfortable silences. It also brilliantly highlights the unusual bond between the three survivors (two are school-going siblings, and the third is the bus driver) as they struggle to reconnect with life and save each other. Aoyama has cited John Ford’s “The Searchers” (1956) as a great influence, which is about an individual burdened by a traumatic event. But Aoyama’s feature is more provocative as well as strangely soothing since it’s leisurely-paced narrative doesn’t offer an easy way out.

3. Battle Royale (2000)

The cultural influence of Kinji Fukasaku’s “Battle Royale” is well-known among the movie-lovers. Based on the best-selling novel by Koushun Takami, the source material received worldwide popularity, inspiring movies, and a separate genre of deathmatch games. From “Hunger Games” to PUBG and Netflix’s “Squid Game,” the scary and duplicitous criminal justice system portrayed here has been mirrored in different dystopian settings. Takami’s novel itself seems to be influenced by William Golding’s classic novel “Lord of the Flies.” Some critics called “Battle Royale”: “Lord of the Flies for the reality TV age.”

Even if you haven’t seen Fukasaku’s adaptation, you might be aware of its storyline and its controversial elements. In an alternate-reality Japan, an authoritative government implements the ‘Education Reformation Act’ to address youth delinquency and related violence. A randomly selected class of junior high school students is taken to a remote, uninhabited island to engage in a bloody game where only one winner can emerge. “Battle Royale” set the benchmark for the era’s exploitation cinema. Its thrilling staging technique and economical storytelling methods perfectly coalesced with an overt yet sharp social subtext. Its influence on pop culture will probably be there forever.

4. Spirited Away (2001)

Animated movies are usually perceived as kid-friendly fare and are defined by their rapid movements and actions. I love Studio Ghibli movies (or anime in general) because they blast that notion and incorporate the Japanese aesthetic tradition of ‘mono no aware,’ which is roughly translated as ‘pathos of things.’ Or, as Lauren Prusinsky beautifully states, “Mono no aware conveys fleeting beauty in an experience that cannot be pinned down or denoted by a single moment or image.”

Similarly, on the surface, Academy Award-winning “Spirited Away” comes across as a tale of a girl slipping into the rabbit hole of a spirit world. It does deal with themes of alienation and loneliness experienced by a girl on the cusp of adolescence. But the beauty of a Miyazaki or a Takahata feature lies in experiencing the mood or atmosphere where the imaginative story unfolds. Whatever I regurgitate regarding the plot of “Spirited Away,” no words can describe the beauty of this powerful experience.

Checkout – All Oscar-winning Animated Movies Ranked From Worst To Best

5. Millennium Actress (2001)

Animation is often seen as a genre aimed at children. Satoshi Kon, in his brief yet splendid filmmaking career, robustly reinforced the notion that animation is a separate storytelling medium. In his animated feature debut, “Perfect Blue” (1997), he used a thriller framework to explore the toxic fandom. With “Millennium Actress,” Kon makes an enchanting journey through the memories of a legendary and retired Japanese actress. One could argue that “Millennium Actress” offers an antithesis to “Perfect Blue” as it presents a bond between an artist and a fan in a more positive and light-hearted manner.

Longing and desire are the important emotions that anchor Kon’s wildly imaginative narratives. But nothing can prepare us for the filmmaker’s dynamic visual ideas. His character states, “Life is the thrill of the chase, even if you’re chasing a shadow.” Similarly, the beauty of any Kon movie lies in the compelling and intricate manner in which he presents his stories.

6. Pulse (2001)

Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s critique of contemporary Japanese society also offers a masterful commentary on our innermost fears. In his unsettling 1997 feature “Cure,” evil was presented as a deadly contagion. “Pulse” is a fascinating companion piece to “Cure,” which navigates its way through the darker sides of the early digital age. Made during the peak of J-Horror, Pulse’s aesthetics of discomfort are rooted in Japanese culture and social transformations.

While “Ringu” (1998) featured eerie phone calls and a long-haired malevolent spirit, “Pulse” is a terrifying parable of alienation in the internet era. At the outset, the episodic narrative seems to showcase the invasion of the paranormal through computers and the internet. But its narrative of people opening the wrong doors in cyberspace presciently speaks of our modern technological dependence and how it contributes to our slow detachment from society. Kiyoshi Kurosawa creates his horror through subtle suggestions. He is particularly masterful when it comes to cleverly using negative space.

7. Twilight Samurai (2002)

Set in the final days of the Edo Period (the 1860s), Yoji Yamada’s “Twilight Samurai” tells the tale of a low-ranking Samurai, Seibei Iguchi (Hiroyuki Sanada), who is caught amidst the winds of economic and cultural change. It’s not a conventional Jidaigeki (period dramas) film but more of a character and societal study. Movies rarely deal with the caste system in feudal Japan and how skilled swordsmen like Samurai are also pawns in the labyrinth of bureaucracy.

Yamada’s protagonist is a master swordsman who can bring down his rival with a single stroke of his katana. But he is a gentle and kind soul who is cautious about hurting others’ feelings, even the ones of those who want to hurt him. Yamada romanticizes the period and the character a little bit. Yet he also interestingly transplants modern themes like the emancipation of women and single parenthood into this 19th-century tale. “Twilight Samurai” is the first part of Yamada’s thematically linked ‘Samurai Trilogy.’ The other two movies –”The Hidden Blade” & “Love and Honor” – are also beautifully understated samurai dramas.

8. Letter from the Mountain (2002)

Takashi Koizumi’s “Letter from the Mountain” is a familiar yet compelling back-to-mother-nature story that unfolds at its own lulling pace with ample poignancy and pathos. It tells the tale of a middle-aged Tokyo couple who move to a farming village in the mountains to ‘heal’ themselves. Takashi Koizumi worked as an assistant to Akira Kurosawa for nearly three decades. His directorial debut, “After the Rain” (1999), was based on Mr. Kurosawa’s last script.

“Letters” features plot threads that are probably quintessential to melodrama, but the delicate observation of the characters, their gentle domesticity, and innate goodness overshadow the melodramatic aspects. In fact, the dramatic core isn’t exaggerated for emotion but rather watered down in a way that allows each crisis to offer a profound meditation on life. The drama is also elegantly enclosed between seasonal changes and the village’s unique cultural events.

9. Zatoichi (2003)

The multi-faceted artist Takeshi Kitano’s remake featuring the iconic blind swordsman turned out to be his most commercially successful venture. Kitano proved to be a master at making sardonic and minimalist Yakuza dramas. He was also successful with tragicomic humanist dramas like “A Scene at the Sea” and “Kikujiro.” “Zatoichi” movies were a huge part of Japanese movie culture, and Kitano doesn’t deviate much from the conventional narrative. Kitano himself plays the titular character of a blind masseur/swordsman who wanders the countryside during the late Edo period (the 1830s or 1840s).

At the same time, Kitano’s “Zatoichi” bears the filmmaker’s distinctive signature elements, including his penchant for offbeat humor and characters. In fact, Kitano turns the film into an ensemble drama, giving prominence to the otherwise peripheral characters and exploring their motivations and history. There might be complaints about poor CGI and fake blood, but there’s a lot to cherish in Kitano’s compellingly staged tale, particularly that unexpectedly delightful tap-dance musical sequence towards the end.

10. Tokyo Godfathers (2003)

“Tokyo Godfathers” is known as Satoshi Kon’s most linear film, and it somewhat lacks the filmmaker’s surrealistic punches. Yet this is one of the most tender and off-beat Christmas stories about society’s outcasts. The story follows three homeless Tokyo residents – an alcoholic gambler, a teenage runaway, and a transvestite – who find an abandoned newborn baby at a dump site. Their attempt to track down the parents and return the baby makes up the rest of this adventurous comedy.

Also, Read – Tokyo Godfathers [2003] Review: A Richly-textured Christmas Dramedy

“Tokyo Godfathers” was chiefly inspired by John Ford’s “3 Godfathers” (1948). But there have been other annoyingly populist Hollywood films involving men and a baby, like “Three Men and a Baby” and “Baby’s Day Out.” But Kon’s treatment is imbued with stark realism, though a moralistic tone rears its head now and then. Like other works by Mr. Kon, “Tokyo Godfathers” evades a genre label, as it surprisingly veers into darker territories before delivering a genuinely hopeful message.

11. The Taste of Tea (2004)

Nothing in Katsuhito Ishii’s filmography prepares you for the weird as well as affecting family drama, “The Taste of Tea.” He is widely known for his contribution to the animation sequence in Tarantino’s “Kill Bill Vol.1.” His feature films, starting from “Sharkskin Man and Peach Hip Girl” (1999), are flamboyant, anarchic, and absurd. In “Taste of Tea,” Ishii finds a perfect family where he can indulge in wildly eccentric tangents and, at the same time, offer a heartfelt study on the quirky, lovable bunch.

Not everything Ishii tries in this episodic yet relaxing family drama works. But Ishii gets full marks for attempting these wildest dramatic arcs in a framework that never lacks imagination. I felt that this movie was an ode to individuality and personal quirks. Ishii shows how the family is all about being at ease with each other while we navigate our way through all the hurdles and troubles. Most importantly, it’s the wonderful, laid-back performances of the brilliant ensemble cast that holds this film together.

12. Swing Girls (2004)

Shinobu Yaguchi is the determined champion of underdogs in Japanese cinema. Though he started making movies in 1990, it was the 2001 feel-good sports comedy film Waterboys that brought him success and a lot of attention. He followed it up with an even more hilarious tale of lazy and bored school girls enlivened by their passion for music. Based on a true account of inexperienced high school girls forming a brass band (Tateshina High School Jazz Club), director Yaguchi offers a straightforward, comedic take on the evolution of a band.

The film follows a group of bumbling girls who want to form a band after their short stint at a practice session as brass band replacements. Although the plot is traditional, Shinobu focuses on the characters and their quirks and creates great empathy for them to drive the story. What’s incredible about the film is how it circumvents the cliches and genre traps the girls get into and makes the events plausible and funny, without the usual preachiness regarding passion or ‘follow your dream’ nonsense, which often the films of this genre succumb to. It’s a laugh riot from start to end. This film sits on the other extreme from the intense and powerful Whiplash. Go ahead and watch it to make your day pleasant.

13. Nobody Knows (2004)

Shocking social dramas have been a part of Japanese cinema since the post-war era. It broke a lot of cinematic taboos, especially when dealing with tales of orphanhood and child abuse. Yoshitaro Nomura’s ‘The Demon’ (1978) followed a financially ruined mother, leaving her children under the care of a timid, irresponsible father. It ends on a chilling note and explores the sense of displacement in an increasingly consumerist society. Hirokazu Koreeda’s ‘Nobody Knows’ similarly deals with a true story (from the late 1980s) of abandoned children.

Checkout – Every Hirokazu Koreeda Movie Ranked

On the surface, like Nomura’s The Demon, Nobody Knows comes across as a horror story that not only zeroes in on the fears of parental abandonment but also showcases how indifference and isolation are part of life in big cities. But there’s more to Koreeda’s feature, particularly in the way he imparts emotional nuance that stops villainizing or demonizing any one person for the children’s fate. In Nobody Knows as well as later in Shoplifters, Koreeda plucks what seems like a sensationalist tabloid story and turns into an unbearable tragic tale of modern society.

14. Howl’s Moving Castle (2004)

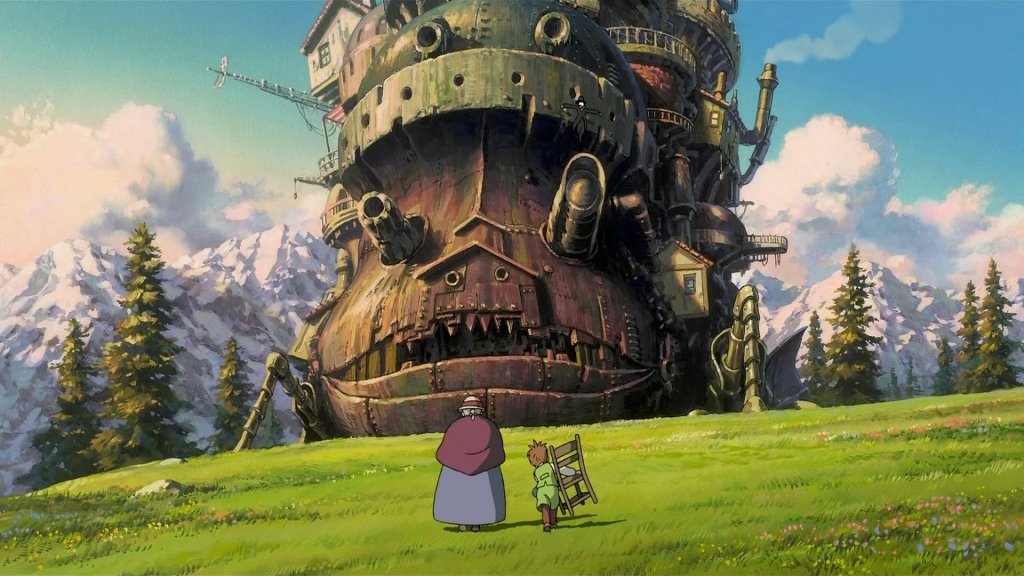

An ingenious Hayao Miyazaki follows up his incredible ‘Spirited Away’ – about the self-discovery journey of a pre-teen girl – with Howl’s Moving Castle. Unlike Chihiro from Spirited Away, Sophie learns the burden of growing up into an adult. But it’s not just the protagonist, Sophie, who is wary of moving on with life. The boy apprentice Markl, Sophie’s fellow cursed beings Calcifer and Howl, plus the terrorizing ‘Witch of the Waste,’ everyone shies away from taking responsibility in life. They struggle and run away from things. Miyazaki seamlessly brings together all these characters and let’s us witness how they solve their issues.

Based on the work of a British writer, Diana Wynne Jones’s 1986 fantasy novel, Miyazaki’s ingenuity lies in how he incorporates the devastation and absurdities of war without trivializing them in a film filled with rich and inventive imagination and stunning aesthetics. It’s like a visionary child left on his own to paint the dreamscape without any boundaries. It’s mesmerizing and thoughtful without being explicitly didactic.

15. Linda Linda Linda (2005)

Nobuhiro Yamashita is known as the master of slacker comedies in the Japanese movie circuit. He made his directorial debut with the 1999 film Hazy Life. But it was the 2005 movie Linda Linda Linda – a comforting slice-of-life drama about high school girls – that brought the idiosyncratic filmmaker his first big success. Straight out of John Hughes’ 80s college-teen drama mix, Linda Linda Linda treads the ‘been there, done that’ trajectory of four idiosyncratic high school girl rock bands that recruit a Korean exchange student as the lead singer just days before a battle of the bands.

Filmmaker Nobuhiro Yamashita’s writing is highly nuanced, particularly in handling the complex emotions of teen angst, friendship, and individuality, and his direction offers a different, if not new, perspective on friendship. The disarming charm of the film comes from the genuine awkwardness and silliness that portrays the character’s vulnerability rather than the goofiness played up for a quick laugh. Mr. Yamashita continues to make dramas about outsiders and the marginalized of Japanese society. A Gentle Breeze in the Village (2007) and The Drudgery Train (2012) are worth checking out in his filmography.

16. Sway (2006)

We hear the phrase ‘female gaze’ nowadays in cinema. It’s all about representing on-screen women as subjects having agency. But the female gaze has also been a potent tool in exploring masculinity, the absurd as well as refreshing aspects of it. One such interesting filmmaker who deconstructs masculinity (like Claire Denis) was the underrated Miwa Nishikawa. Her films are often about flawed men trying to fit themselves in an unforgiving society. In her second feature film, Sway (2006), Nishikawa takes up an interesting crime/drama premise.

We know that any human relationship in itself goes through the full spectrum of emotions, and cinema has been at the forefront of exploring it in commercial and art-house space. However, it’s the siblings’ relationship that cinema hardly examines beyond the conventional drama that neatly ties in the end. Sway sits outside the traditional exploration of sibling relationships gone sour. The micro investigation into the relationship of siblings shows the undercurrent of years of frustration and deeply seated anger between fashion photographer Takeru (Joe Odagiri), who managed to leave the house to make a career in Tokyo, and his older brother Moniru (Teruyuki Kagawa). The latter has stayed behind to run the family business.

Their relationship starts to crack when a murder investigation of their mutual friend commences. The conflict becomes a psychological drama when the brothers’ responses to it become very complex. It plays out like a chess game but is more organic in its development and fluidic in its progression. Teruyuki Kagawa’s performance should probably go down as one of the great yet lesser-appreciated performances of the century.

17. I Just Didn’t Do It (2006)

While Japan’s criminal justice system is known for its unbelievably high conviction rate (99%), it’s entirely different whether it guarantees justice. The deeply ingrained shame culture, repeated denial of bail, and the extended periods of pre-trial detention have made the critics of the nation’s criminal justice system come up with the term ‘hostage justice system.’ Masayuki Suo’s riveting and infuriating drama, “I Just Didn’t Do It,” shows how inherently flawed and inhumane Japan’s court system is. The narrative follows Teppei Kaneko (Ryo Kase), a young man on the way to his job interview.

In the crowded commuter train, Teppei is accused of molesting a 15-year-old girl. Teppei maintains that he didn’t do it, even when the detectives give him a choice, i.e., plead guilty and pay a fine or wait in prison until his innocence is proved after the torrid court proceedings. Earlier in the film, we see a lecherous middle-aged man caught molesting a woman, who begs the police for pardon, and he is let go with a fine. We don’t know much about Teppei or if he is really innocent. In fact, like Justine Triet’s Palme d’Or award-winning film, “Anatomy of a Fall,” the focus is relatively less on the crime and more on the legal proceedings. When the rewards for admitting guilt (even if you are innocent) look a better option than trying to prove one’s innocence, then there’s something definitely wrong with the justice system.

One could be initially doubtful of Teppei’s proclamation of innocence. But gradually, like one of Teppei’s lawyers, we realize that Teppei might really be innocent. The case against Teppei might seem like a cut-and-dry case. But Masayuki Suo’s direction and screenplay infuse tremendous tension and anticipation into the proceedings. Mr. Suo is best known for his comedy dramas, “Sumo Do, Sumo Don’t” (1992) and “Shall We Dance?” With “I Just Didn’t Do It,” he offers a scathing portrait of a system more concerned about approval ratings and saving face than the truth.

18. Paprika (2006)

When Hollywood was cheering and awarding mushy animated comedies like Happy Feet and Ratatouille, Japanese animator Satoshi Kon – unfortunately in his last movie – showed us the startling potential of animation as a genre in his no-holds-barred wild ride into a nightmare titled Paprika. Movie lovers might be aware of this anime since it’s often cited as the prototype work for Nolan’s Interstellar. But in hindsight, Paprika quintessentially blends the ideas Satoshi Kon earlier experimented with within his films: the notion of disjointed reality, interference of memories in the present, and identity.

In the movie, Dr Atsuko Chiba gains the ability to enter their dreams. This device acts as a vessel for expressing herself, and she inhabits the dreamscape without any constraints. However, when the device gets stolen, reality and dreams begin to merge. Consequently, Dr. Atsuko Chiba embarks on a mind-bending chase to find the person who possesses the device. Paprika would immediately draw your attention, but it demands your complete submission to Kon’s perplexing vision. Eventually, Kon’s vision of a dream turning into a nightmare reminds us of the digital escape, which becomes a vent for people’s repressed emotions.

19. United Red Army (2007)

Director Koji Wakamatsu is the bad boy of Japanese cinema. Alongside Seijun Suzuki, he led the provocative and experimental pack of film-making in the 1960s, which assaulted one’s senses with violence, nudity, as well as melange of radical politics. It also featured stunning cinematography and fascinating editing techniques.

In United Red Army, Wakamatsu offers a raw and unconventional portrait of the Japanese student movement in the 1960s and 1970s and how it gradually chose the path of nihilistic violence due to intense radicalization and state oppression. It’s a trip down memory lane for Wakamatsu since he is known for his sympathies with radical politics during the 1960s. But it’s not a work of nostalgia. Wakamatsu unflinchingly looks at what went wrong with the Red Army Factions. And how youngsters were pulled into the ideological swamp and eventually demolished by the State’s formidable power.

20. The Mourning Forest (2007)

Naomi Kawase is one of Japan’s most respected female filmmakers, who has also garnered international attention, unlike other Japanese contemporary female filmmakers like Miwa Nishikawa, Naoko Ogigami, Yuki Tanada, and Momoko Ando. She won the Camera d’Or for her debut feature Suzaku (1997) at age 28, and hence, possibly the youngest filmmaker to win that award. But even before her debut feature, Naomi Kawase proved her talent through experimental documentaries that focus on her family’s women and their traumas. Later, Kawase described her narrative cinema as fiction with the documentarian’s gaze. This was true with her next two feature films: Shara (2003) and The Mourning Forest (2007).

Kawase’s work mainly focuses on the status and place of women and other marginalized populace within Japan’s modern society. The Mourning Forest is one of Kawase’s best as a filmmaker, which sees two individuals mourning over the loss of their spouses. Unlike Western films, which often take a simple & straightforward approach, Kawase imbues the narrative with idiosyncratic Eastern sensibilities. A younger female nurse, Machiko, takes care of a dementia-afflicted elderly man, Shigeki, in a retirement home. Their life collides inexplicably when Shigeki walks into the forest, possibly thinking of visiting his wife’s grave. Machiko goes after him, and the dense forest becomes a literal and figurative realm for them to open up about their loss and grieve without any inhibition. The Mourning Forest is a challenging but rewarding watch for a patient viewer. It won the Grand Prix award at Cannes.

21. Still Walking (2008)

Hirokazu Koreeda’s sumptuously layered masterpiece unfolds in just over a day as a family comes together for the 15th death anniversary of the eldest son. It’s about the still walking, whose life choices, as well as their conversations, somehow revolve around the memories of the dead person. What do we talk about when different generations of people come together and try to appreciate each other’s company irrespective of one’s flaws and personal quirks? Or what do we fail to talk about? It’s in the things said and left unsaid lies the profundity of Koreeda’s nuanced creation.

If we keep away the surface-level appreciations like Koreeda being an heir to Ozu and try to comprehend the many depths of ‘Still Walking,’ we can unveil a lot of truths about human behavior. Apart from Koreeda’s deft touch, the magnificence of the film lies in its powerful ensemble cast. Particularly, special mention should go to the on-screen mother-son pair of Hiroshi Abe and Kirin Kiki. Still Walking is one of those films that make me happy that it exists, and the thought that I can watch it as long as I am alive comforts me.

Related to Best Japanese Movies – Still Walking [2008]: A Stroll through Butterfly Lane

22. Love Exposure (2008)

Sion Sono, the outrageous Japanese auteur who carries the anarchic filmmaking style of Nagisa Oshima and Seijun Suzuki, made his first feature film in 1987. But it was the sensational horror/drama Suicide Club (2001) that earned him widespread attention. The epic and free-wheeling four-hour-long saga, Love Exposure, was his most passionate project. It’s an unflinchingly subversive work that comes out of a collision between religion and perversion, hate and love, anarchy and cynicism. The film is dense, thought-provoking, and at times overwritten, but it is an incredibly rewarding experience to sit through. Love Exposure is a spectacular roller-coaster ride through the lives of messed-up characters who form their agency to defy societal conventions, and these characters enjoy their rebellion and wallow in fatalism.

The source of torment & acute suffering for all three young characters in the film is their dogmatic parents. They are sick personalities who shove down their guilt & failure in their duty to their children. The pain propels them on the path of perversion & travesty that challenges every societal preaching, including the alleged sanctity of religion. Sono juggles themes of patriarchy, sexual abuse, and the varying scales of evil, perversity, and, of course, love in a striking way.

23. Tokyo Sonata (2008)

Tokyo Sonata is definitely an unexpected departure from the unconventional horror films that largely mark Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s career. Here, he deals with the psychological and social impact of unemployment on an individual and a family. The film’s central character is a white-collar worker whose work in the administration is made redundant. Japan might have recovered from the prolonged recession of the 1990s. However, the impact of the transformed job market and the subsequent changes were dramatic. Though the country’s suicide rate showed a downward trend in the 2010s, when this film was made, Japan’s suicide rate was the second highest in the industrialized world.

Tokyo Sonata also offers an interesting portrait of the wife’s alienation, who is caught under the trap of predictable domesticity. The younger generation doesn’t have it better, either. Wars and growing social inequality spell doom for the future. The problem with the film is perhaps Kurosawa’s addition of subplots and conflicts in the third act that aren’t convincing and strike a lot of false notes. Yet I prefer Tokyo Sonata to many other well-made but mushy Japanese dramas.

24. Departures (2008)

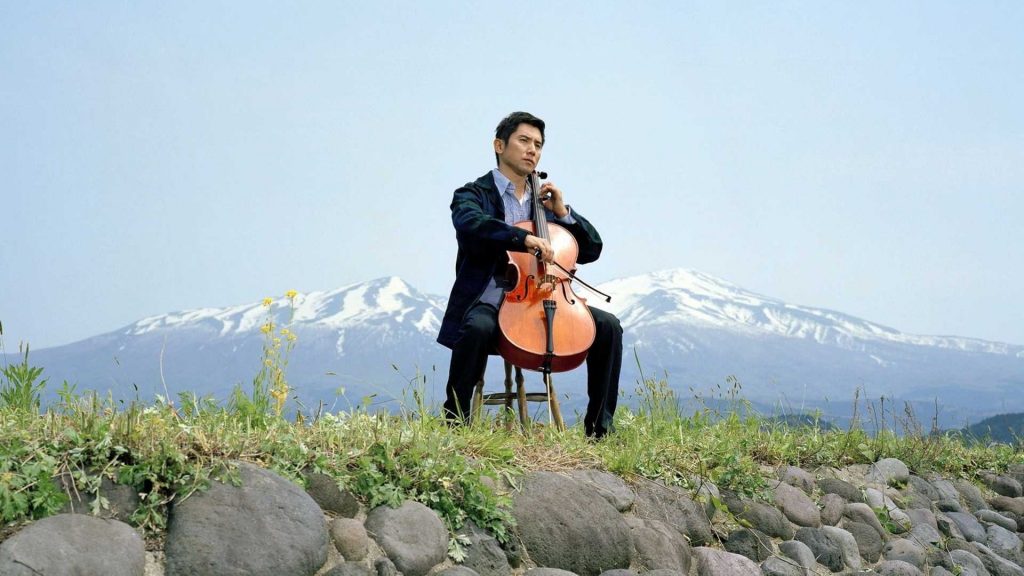

Yojiro Takita’s Academy Award-winning Departures is a very predictable yet heartwarming tale that deals with the themes of duty, love, mortality, life, and death. The film revolves around Daigo Kobayashi (Masahiro Motoki), an orchestra Cellist in Tokyo whose job is made redundant due to low attendance. Unable to find a job in the big city, Daigo moves to his provincial hometown with his wife (Ryoko Hirosue). Daigo follows a misleading ad that makes him think he is applying for a travel agent job. But he ends up as an apprentice for the town’s ‘encoffiner’ Ikue Sasaki (Tsutomu Yamazaki). It’s a business devoted to the ceremonial preparation of dead bodies before cremation.

Departures feature a well-worn narrative thread: a central character finding hope and stability in the unlikeliest of places. Nevertheless, it offers a fascinating window to perceive the cultural outlook on death in Japanese society. Despite the overt sentimental notes, the film works due to Takita’s quiet and measured tone. Takita’s brilliant symmetrical compositions juxtapose the harshness of death with the gentle treatment of the mortal remains. Takita also looks at the contrasts of an individual who repeatedly faces death and yet is in the process of creating art.

25. Fish Story (2009)

Trust the Japanese to make an entertaining off-beat comedy out of an apocalyptic scenario. Spanning several decades and following multiple characters, Fish Story is the tale of a song that saves the world. It has the premises of Hollywood disaster blockbusters like Armageddon and 2012, but it takes that scenario of giant comet collusion into delightfully different directions.

The film opens in 2012, and it’s just five hours left for the total annihilation of the human race. A middle-aged man walks through the deserted streets to find a record shop that’s open. The relaxed record store owner puts on a record and, over different flashback sequences, talks about the ‘Fish Story,’ a song by an obscure 1970s punk band that could be the secret key for human survival. I know the plot of Fish Story sounds gimmicky and outrageous. However, the director Yoshihiro Nakamura walks a tightrope to build a satisfying, multi-layered narrative around this incredibly far-fetched core story. ‘The Foreign Duck, the Native Duck, and God in a Coin Locker’ (2007) is another delightfully weird feature from Nakamura.

26. The Secret World of Arrietty (2010)

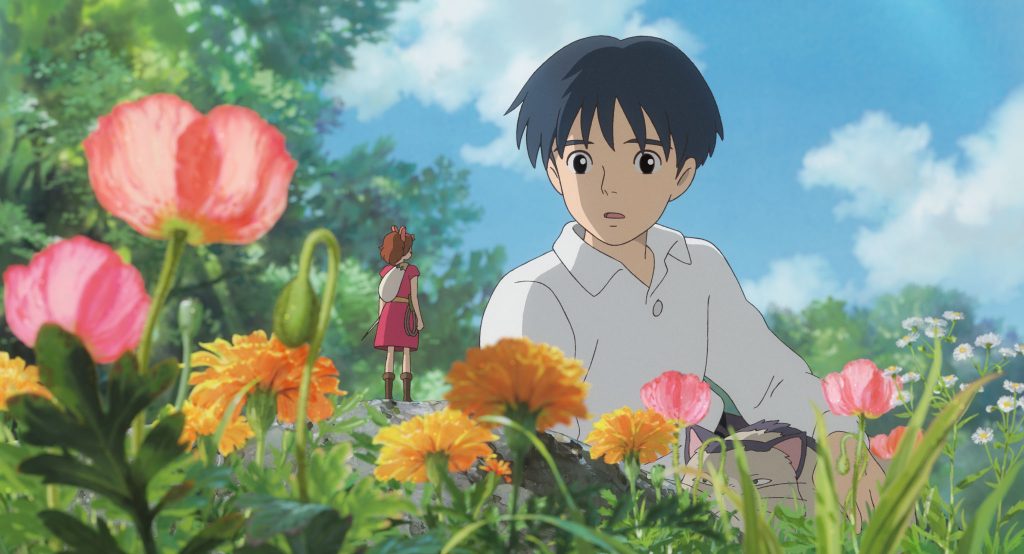

Based on Mary Norton’s 1952 children’s fantasy book, The Secret World of Arrietty is directed by Hiromasa Yonebayashi and co-written by Hayao Miyazaki. It’s a project Miyazaki was trying to make for nearly 40 years, i.e., even before his involvement with Studio Ghibli. Our heroine, Arrietty, is a plucky red-haired miniature girl who lives in the ocean of subterranean grass world. She is befriended by a ‘human bean’ named Sho, a terminally ill teenager who comes to live with his aunt in the countryside of Tokyo.

Studio Ghibli features often visualizes everyday events and interactions with startling details and tenderness. In ‘Arrietty,’ the lush miniature world is created in a painstakingly detailed manner, and Arrietty’s life brings out the magical in the mundane. There’s a timeless quality to this tale of friendship. For the Miyazaki and Takahata fans, Secret World of Arrietty might lack the filmmakers’ wild fantasies and may seem too crowd-pleasing. Yet, it’s an enjoyable, heartfelt fable with astounding animation. Mr. Yonebashi followed it up with an equally beautiful tale of a 12-year-old misfit, ‘When Marnie was There’ (2014).

27. 13 Assassins (2010)

The political power in the hands of a wrong man can bring ruin and leave an irreparable scar on the social fabric. History has always given us such tyrant and dictator figures as a constant reminder of the implications. Takashi Miike’s ’13 Assassins’, carrying the oeuvre of Seven Samurai, deals with the fear and threat of such political dynamics that are on the rise while samurais are living in peace.

It spends the first hour assembling a band of samurais to assassinate a psychotic, impulsive, and fearless half-brother of Shogun, who would soon become a prominent figure in Shogun’s ministry. Akira Kurosawa would be proud of this film and some more. Keeping visual pallets dark and toning them down to maintain the narrative’s coldness is a visual feat where art and action exist simultaneously.

28. I Wish (2011)

Although Koreeda’s films are mostly about families and relationships, children are the most who suffer. Ryota from ‘Still Walking’ has to carry the burden of his dead elder sibling; no one takes notice of Yuichi from ‘Maboroshi’ after the death of his father; two children switched at birth in ‘Like Father Like Son’ are never asked for the consent to live their blood parents. And in ‘I Wish’, parents decide the fate of their children based on their economic convenience.

In the face of the inevitability of family disintegration, Koichi and Ryu chase a legend in the hope of uniting their family and, hence, living together. The plot may sound very sentimental, and Koreeda does pull off the wondrous element with the tinge of bittersweet reality. In fact, he merely uses this narrative set-up as a tool to branch out the narrative and study the place of an individual beyond a family unit, as messy, sad, and wonderful as it can be. As much as Koreeda’s restrained writing and deep understanding of familial dynamics help the film, kids’ and adults’ splendid performance brings the characters alive and showcases one’s reality with all the tenderness intact.

29. Kotoko (2011)

From Teinosuke Kinugasa’s silent classic Page of Madness (1926), avant-garde cinema in Japan has established its presence. In the 1960s, with the advent of the Japanese New Wave, avant-garde filmmakers employed unique imagery to explore the nation’s shifting political and cultural landscape. Toshio Matsumoto, Shuji Terayama, Yoshishige Yoshida, and Susumu Hani were some of the prominent filmmakers of the era. But just when the experimental nature of Japanese cinema seemed to be dwindling in the 1980s (of course, there was Obayashi) came the avant-garde black-and-white film to solidify and reawaken the experimental spirit of Japanese cinema. The film titled Tetsuo: Iron Man (1989) chronicled a man’s agonizing transformation into a metal. From then on, Tsukamoto has made plenty of cult horror films, including Tokyo Fist (1995), Vital (2004), and Haze (2005).

However, Tsukamoto’s most deeply unsettling work among all was his 2011 psychological horror film, Kotoko. It revolves around a mentally disturbed single mother grappling with alienation. Her feelings of fear and rage further facilitate her descent into the deepest pits of despair. Kotoko, played by singer-songwriter Cocco – who has also crafted the original story – suffers from acute hallucination. She develops an abnormal illusion of seeing doppelgangers of people around her. It results in grisly consequences that may subsequently turn dangerous for herself and her little baby. Director Shinya Tsukamoto draws us cleverly into the headspace of Kotoko and vicariously shows us the horrors of unconstrained hallucination & paranoia.

Related to Best Japanese Films of the 21st Century – 20 Best Japanese Horror Films

30. Chronicle of My Mother (2011)

Based on the autobiographical fiction of Yasushi Inoue, Masato Harada’s understated drama offers a moving paean for mothers and is also an intimate study of memory & loss. The complex mother-son relationship at its center avoids easy sentimentality and is benefited by the phenomenal performances of Kirin Kiki and Koji Yakusho. Yakusho plays a successful author and a demanding patriarch with a repressed past. He is bitter with his aging mother for her emigration to Taiwan with her daughters during the turbulent post-war period. But ironically, the resentment that lacks true understanding of his mother’s plight serves as the inspiration for his work.

Some might complain that the characters are kept at arm’s length. However, the deliberately muted pacing keeps the drama organic and gradually delivers impactful emotional punches. Eventually, it brilliantly conveys the sadness of a life drifting away and how important it is to make peace with our past. Director Harada also pays ample visual tribute to Ozu’s post-war family dramas.

31. Like Someone in Love (2012)

In the last phase of his career, Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami chose the path to be recognized as a world filmmaker. He went to Tuscany to make the playful and ambiguous romantic drama Certified Copy (2010). In 2012, he went to the neon-lit sprawl of Tokyo to make the provocative drama Like Someone in Love with an entirely Japanese cast. The basic plot focuses on the Japanese social phenomenon of paid dating or compensated dating. It usually denotes the practice of older men giving money to young women – college students or high-school girls – for sexual favors. The narrative’s central character, Akikio, a stressed-out college student, is gradually revealed to be moonlighting as a call girl. Her client for the night is an elderly and retired sociology professor, Takashi.

Takashi’s interest in the woman is not sexual but rather a channel to ward off his loneliness. When Akikio’s jealous and possessive fiancé, Noriaki, enters into the narrative, further layers are revealed. In terms of writing and direction, Like Someone in Love largely doesn’t come across as the work of a touring filmmaker. It’s a tale of unusual confrontations, and yet it’s a deeply contemplative film about love and the illusions we build around it. Love could be beautiful, but it’s not always a cuddly thing. Kiarostami looks at the darker shadings beneath one’s idea of love. Hence, the important word in the title is not ‘love’ but ‘like.’

32. Wolf Children (2012)

Childhood, memory, and family are some of the important and recurring themes in the works of anime filmmaker Mamoru Hosoda. Early in his career, Mr. Hosoda was given the chance to direct Studio Ghibli’s Howl’s Moving Castle. But since his creative vision of the film didn’t fit with that of the studios’, he quit the project. Later, he made two successful anime features – The Girl Who Leapt Through Time (2006) and Summer Wars (2009). Though Summer Wars enjoyed worldwide success and was championed as his best work by many critics, it didn’t work for me. Apart from the tiring clichés, the fun and unique premise of Summer Wars soon deteriorates into a mediocre family drama.

Wolf Children, on the other hand, is a more focused and emotionally involved drama on an unconventional family unit. It revolves around a single mother, Hana raising her two children, born out of love and relationship with a werewolf named Okami. The werewolf portrayed here is pretty different from the Western myth of werewolf, which is a staple element of the horror genre. Hosoda uses the magical premise to look at cultural and social issues like racism or the prejudice channeled against single motherhood. Wolf Children was made by Studio Chizu, co-founded by Hosoda, and he made two more films under that banner – The Boy and the Beast (2015) and Mirai (2018).

33. Like Father Like Son (2013)

Hirokazu Koreeda tackles a complex emotional quandary that one might hardly imagine, let alone be in it. It’s the story of children who are switched at birth. Sounds like something that could happen only in films? However, Koreeda not only manages to fill it with tangible emotions, but his deceptively simple yet intricately written narrative draws us into the lives of the devastated parents and gradually nudges us into deeply understanding them. In fact, he uses the plot as a facade to incisively examine what it means to be a family, which he further explored in a different social setting in Palme d’Or winner Shoplifters.

The film carries emotional heftiness of such magnitude that it could drain the soul out of any parent. The two concerned families are economically and socially far apart, so when they confront the fact and exchange their blood child over the weekend, their lives start to crumble. Kore-eda powers the film with flawed characters. He shows us the flaw even before the plot kicks into place. That gives him leverage to not judge these characters or their actions through the lens of moral codes. His immensely restrained narrative brims with profuse empathy for the characters, their lives, and the tragic circumstances they are in. But the real tragedy is that the two families never involve their children before deciding on their fate. Families never consider their consent.

34. The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2013)

Isao Takahata’s last film as a director, The Tale of the Princess Kaguya, is one of the best works in his decorated filmography, consisting of masterpieces like Grave of the Fireflies and Only Yesterday. Called the ‘giant sloth’ by his friend and colleague Miyazaki-san, Princess Kaguya was Takahata-san’s feature-length anime in 14 years. Sadly, it was also his last film.

In this film, he interprets the 9th or 10th-century classic Japanese folktale, The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter (the oldest recorded folktale in Japan), which took eight years and a budget of 5 billion yen. Simplicity and ethereality of life, and women’s place in the patriarchal society form the crux of the narrative. Steeped in the folklore about a magical baby, “The Tale of the Princess Kaguya” is an eternal story of girls forced to conform to the social and cultural norms about their role in society. Even the ending signifies the spiritual death of Princess Kaguya, who goes on another journey, parting her ways with her parents, into the unknown. It’s a lyrical and significantly restrained anime with elegant visuals of impressionistic style animation and compassionate characterizations.

35. Why Don’t You Play in Hell? (2013)

Is film-making an act of lunacy? With a gleeful smile, Sion Sono says yes while navigating through torrents of blood and heaps of hacked-off limbs. Sion Sono’s movies often resist plot description. Not because it’s tough to put it into words. When everything about Sono’s story is described, it might come across as plainly ridiculous or absurdly carnivalesque. So it’s better to just dive into the mayhem in ‘Why Don’t You Play in Hell?’ and follow the renegade and wildly enthusiastic film-making crew who call themselves ‘Fuck Bombers.’

Maintaining a frantic level of energy and a manic tone can exhaust a movie viewer, which is something I deeply felt with a few acclaimed Japanese flicks like Survival Style 5+ (2004) and Memories of Matsuko (2006). But in Sion Sono’s universe there’s no reasonable or rational behavior that everything becomes a delicious metaphor or meta-textual commentary. Oh, the things filmmakers have to do to conjure the best shots!

36. The Tale of Iya (2013)

Tetsuichiro Tsuta’s Tale of Iya is one of the obscure gems in Japanese cinema. Shot in the scenic Iya Valley region in the Tokushima prefecture, the film deals with the hardships of rural life. Its central drama revolves around a young girl named Haruna, who is raised by an elderly mountain man. The invasion of modernity in the isolated mountain community is signaled by a construction tunnel project. But the film is not a straightforward drama. It also carries a Weerasethakul-esque mystery and light surrealism to it that makes things more complex and stellar.

Narratives of city folk moving to the countryside to embrace the tranquility of idealistic rural life are oft-repeated in 21st-century Japanese cinema. Tale of Iya offers a less sentimental and more challenging take on such familiar narrative threads. It unflinchingly shows us what it means to live in a place totally untouched by modern life.

37. Little Forest (2014)

Jun’ichi Mori’s Little Forest is a two-part adaptation of the popular manga series (illustrated & written by Daisuke Igarashi) of the same name. It’s a 4-hour slice-of-life drama about a young woman in a quest for self-sufficiency who lives off the land and cherishes seasonal cooking. She leaves her life in the big city and settles back in her hometown, a picturesque mountain region in Tohoku. It’s a brilliant meditation on living among nature. However, it doesn’t romanticize the protagonist Ichiko’s struggles.

It unfolds with minimal dialogue, and the simple storytelling methods make it genuinely moving. Ai Hashimoto, in the central role, offers a gentle, understated performance that perfectly sets the mood. I first learned about Little Forest through the 2018 Korean adaptation, starring the tremendously charming Kim Tae-ri. The Korean version is a nice, feel-good take on the manga series. The Japanese adaptation is more profound, offering a highly unique cinematic experience for nature and foodie lovers.

38. 0.5mm (2014)

Japanese filmmakers often take a deceptively simple subject and process it through an undeniably complex perspective. The result can be a deeply profound exploration of the national, emotional, and social psyche. Momoko Ando’s 0.5 mm is one such simple tale that gradually turns into an epic character and social portrait. Momoko Ando has adapted her own novel and recruited her real-life sister Sakura Ando – known for playing the central role in Koreeda’s ‘Shoplifters’- to play the protagonist. It chronicles the unusual odyssey of the enigmatic Sawa Yamagishi, a home care nurse who, after losing her job, finds solitary elderly men and gets herself involved in their lives. Actually, that’s putting it lightly. Sawa is a very caring person and sometimes her behavior or intention raises compelling ethical questions.

Nevertheless, she has a knack for understanding elderly people’s pains and trauma. Moreover, all her strange counters with the isolated elderly populace address many of the contemporary social problems in Japan. Most importantly, Momoko Ando handles the challenging and thought-provoking subject with a darkly comic tone. It is a critique of the patriarchal structures and systems. But she does it through layered personalities and avoids archetypal characterizations as well as an overt idealistic tone.

39. Our Little Sisters (2015)

‘Our Little Sisters’ is Hirokazu Koreeda’s quietest and sublime film which possesses a strong emotional undertone. It delicately handles the fractured familial narrative without the flab of ostentatious dramatic tension that films of this genre usually carry. Three sisters, living by themselves, meet their young, shy step-sister at their father’s funeral. She nursed her bedridden father before he succumbed to death. They invite the teenage sister to stay with them.

What could have turned into a film with multiple conflicts and a half-baked dramatic resolution, Koreeda turns around by taking the less traveled path and exploring each sister’s deepest desires and fears. He looks at how siblings can come together, support each other, survive, and thrive when their parents are gone. He captures the unfussy mundane moments shared among the sisters. In fact, the mundane in the hands of this filmmaker looks magical. Koreeda mines dramatic moments from fleeting moments of everydayness. He finds resolution in the simple act of walking their mother back to the station.

40. Happy Hour (2015)

In one of the sequences that lasts for more than forty-five minutes, we see four long-time friends attending an abstract therapy session. It actually plays in real time. One might wonder what purpose it serves, and it would be difficult to defend if someone outright calls it boring. Ryusuke Hamaguchi captures such banal details found in the most mundane facets of life. This kind of narration and direction pushes us to reflect on the characters rather than sequentially following the narrative.

Also, Read – Happy Hour was featured in our list of the 75 Best Films of the decade (2010s)

‘Happy Hour’ observes the uneventful intersection of the quotidian lives of these female friends, caught up in a thankless routine that gradually takes a psychological toll on them. While the world proves hostile and underwhelming to their expectations, they find solace in each other’s company. The long first act establishes the characters to a degree we feel we know them personally. Once Ryusuke Hamaguchi achieves it, he kicks in the drama with these friends, reevaluating their life choices and taking the necessary steps to better them, even if it costs them their relationship at home.

The intimidating length of five and a half hours might turn you off. Nevertheless, it’s an intimate film, deeply entrenched in Japanese socio-culture, whose branches touch the universality of friendship and love. This is not only one of the best Japanese films of the century but also the best work of Hamaguchi so far in his filmography.

41. Sweet Bean (2015)

If you need one reason to watch this film, let that be a step-by-step tutorial on making the perfect dorayaki by Kirin Kiki.

Sweet Bean is a traditional sweet snack of red bean paste sandwiched between two pancakes. Kirin Kiki’s character brings an extra freshness to the sweet bean, making middle-aged Sentaro (Masatoshi Nagase) joint blossom in a busy bakery shop. Just like the dish, she makes this routine bittersweet narrative of misfits finding their way a comfort movie. Naomi Kawase’s narrative – her most accessible film and a better place to start her oeuvre – has all the ingredients for a mushy melodrama. An older woman locked in isolation due to leprosy, a lonely teenage girl, and a middle-aged man with a troubled past.

In the hands of any lesser writer-director, this could have been a template story relying on loud drama that would end as you would expect. However, Naomi takes a less-traveled path and renders these normal mortal beings’ struggle genuine & honest, and observes their little joyous moment without a hint of theatrics. This film moved me; the characters ring true to me, and Kirin Kiki’s charming performance cuts very deep.

42. Harmonium (2016)

Koji Fukada seems to ask how much sacrifice and emotional burden one needs to put up with to uphold the illusion of idealized family life in this haunting drama. Harmonium tells the tale of a family broken down by the arrival of an intruder. It has a Hitchcokian story with aesthetics that bring to mind Michael Haneke. I think the film would offer a more satisfying experience the less you read about its plot.

It’s especially important to experience the surprising turn the narrative takes at the end of the first half. The film does lose its subtle touch in its final act. Yet it’s a pitiless and deeply affecting examination of guilt and sin. One of the notable aspects of Harmonium is how the Japanese star actor Tadanobu Asano plays the intruder, who is also an individual with felony conviction. There’s something poignant as well as unnerving about the actor’s stoic calmness.

43. In This Corner of the World (2016)

Sunao Katabuchi’s ode to the resilience of humanity is based on Fumiya Kono’s manga series. Set during World War II, In This Corner of the World is a portrait of a young woman named Suzu, who moves to a port city after marriage at the height of the war. Suzu is called ‘clumsy’ when it comes to handling the domestic chores. But she possesses a great talent for drawing and weaves imaginative tales out of the stark reality. When the war escalates, the situation at the domestic front becomes harder with rationed foods, shell attacks, and diseases.

In this Corner of the World is an intimately detailed study of human fragility in the face of war, poverty, and fear. It’s a tale of a woman caught in the relentless daily grind with no visible signs of recovery. Similar to Takahata’s Grave of the Fireflies, Katabuchi’s anime is profoundly tragic and is also devoid of melodrama. Moreover, Katabuchi’s immersive sketchbook aesthetic is filled with great details while visualizing the quotidian lives of the civilian populace during the war. I particularly recommend the extended cut, which runs for 168 minutes.

44. Your Name (2016)

Makoto Shinkai essentially makes boy-meets-girl anime. But the way he combines high concepts, emotional storytelling methods, and soothing imagery has made him acknowledged as the supreme craftsman of the anime industry. He understands adolescence and the whole bunch of emotions associated with that phase in life. While Miyazaki gently nudges us to perceive the good, bad, and gray areas of society like a father figure, Shinkai is on the level with youngsters and captures their anxieties and joys from myriad angles.

Your Name – the box-office sensation in Japan – was the most defining work of Shinkai’s career. The astounding anime is a magical mix of time travel and body-swapping glued together with a sweeping teen romance for ages. Shinkai isn’t interested only in fantastical elements of the idea so as to run wild with the romantic narrative. He smartly weaves the principal characters – Taki, a teenager attending high school in Tokyo, and Mitsuha, living in a fictional town in the mountains, who find themselves torn between modernity and tradition and find new empathy for the other gender due to inexplicable events of body swapping. What starts as a comedy of errors turns into a profound depiction of emotions that takes you to a new shore.

45. Shin Godzilla (2016)

The long and storied Godzilla franchise receives an intriguing reboot with Hideaki Anno & Shinji Higuchi’s “Shin Godzilla.” This twenty-ninth Toho-produced Godzilla movie reimagines Gojira as a creature metamorphosing in the aftermath of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster (during the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami). What’s particularly exciting about “Shin Godzilla” is the incorporation of real-world political games in managing the monster rampage. While the original “Godzilla” (1954) raised concerns about the atomic age, “Shin Godzilla” explores the nation’s militaristic concerns in the region.

The endless debates in conference rooms between authorities and diplomats render the monster into something strictly figurative as Anno raises pertinent questions about the world we live in. The film also features entertaining monster action moments. The blend of CGI, miniature effects, and suitmation looks quite convincing. Moreover, the stages of Godzilla’s metamorphosis offer extraordinary imagery. “Shin Godzilla” doesn’t have much character development or clear-cut messaging, but it’s a fascinating reflection of the geopolitical realities.

46. Hanagatami (2017)

Nobuhiko Obayashi – the Japanese filmmaker known for the indescribable cult horror classic House (1977) – was born for making cinema. He spent his childhood in the backdrop of WWII. At the age of six, he started with hand-made animation films, and by the time he finished university, Obayashi made his first short film (The Girl in the Picture, 1958). A decade later, Obayashi made his first feature film, and he has often cited Jean-Luc Godard as one of the chief influences in his early film-making days. But Obayashi soon became a director of commercials and returned to feature films only in 1977 with House. From then on, Obayashi persisted with an eclectic style of filmmaking brimming with manic imagery and marvelous spontaneity.

Also, Read – Hanagatami featured in our list of the 75 Best Films of the decade (2010s)

Obayashi’s final four works in the 2010s focused on the WWII era. Casting Blossoms (2012), Seven Weeks (2014), and Hanagatami (2017) is seen as his unofficial ‘War Trilogy’. Hanagatami, in particular, was his passion project. He wrote the script for the film back in the 1970s. Obayashi conjures up his comprehensive experience in film-making and conceives a phantasmagorical cautionary tale on the perils of War spread across three hours and aided by a dense narrative. He concisely blends well-written characters, symbolizing different ideologies of the then-Japanese youngsters, with hyper-realistic visuals and meditative storytelling. Layered with esoteric motifs and visuals, he manages to make a reflective drama about the wasted youth of Japan’s war years.

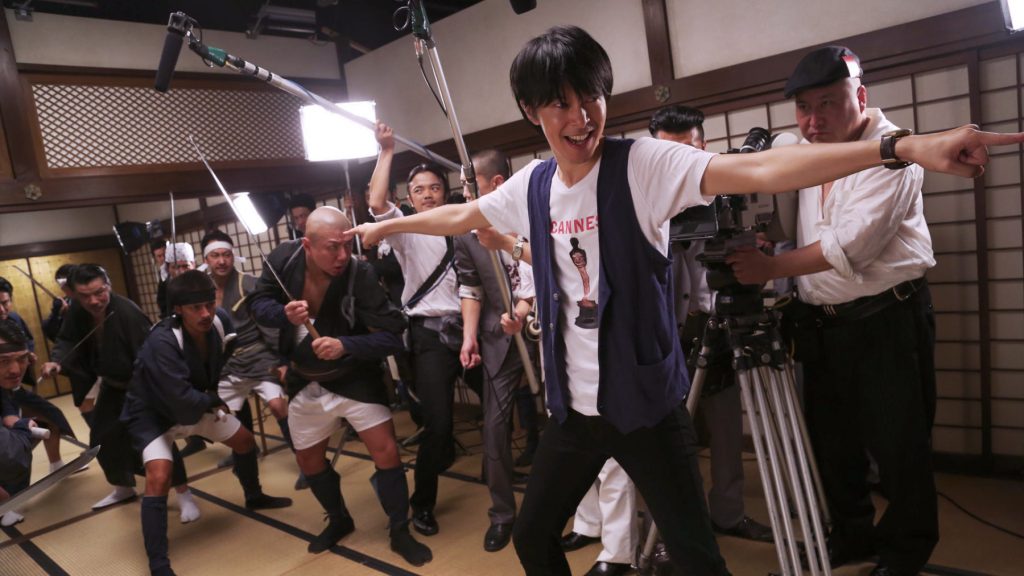

47. One Cut of the Dead (2017)

There are two must-dos to thoroughly enjoy Shinichirou Ueda’s wild comedy One Cut of the Dead: go into the movie blind and don’t judge the movie based on its first 35 minutes. It opens with a cliched premise of a guerilla filmmaking crew engaged in a one-take zombie-themed horror. But real zombies show up, and bloody chaos ensues. I know you might have all come across this in Romero’s stale zombie flick Diary of the Dead. However, The soul and fun of Ueda’s film lie in what comes after.

Using a fascinating structural trick, writer/director Ueda has paid an innovative tribute to micro-budget horror film-making while also making fun of the silliness and imbalances surrounding such a workplace. Even though different in terms of tone and structure, One Cut of the Dead partially reminded me of Sion Sono’s wildly imaginative ‘Why Don’t You Play in Hell’ (2013) and American indie drama ‘Living in Oblivion’ (1995).

48. Shoplifters (2018)

Hirokazu Kore-eda has delivered atleast (arguably) four best Japanese films of the last decade, including Shoplifters. 2018 Palme d’Or winner Shoplifters is yet another thoughtful addition to one of the most humanistic filmmakers of contemporary cinema – Hirokazu Kore-eda. Having explored how true fatherhood doesn’t just involve a blood relation in his 2013 film “Like Father Like Son,” Kore-eda puts together many societal misfits questioning the very essence that goes into making a family.

Similar to the works of the old Japanese master Mikio Naruse, Koreeda’s style is deceptively simple. He gradually pulls us in through his compassionate writing skills and heart-warming performances. These rich characters with profound depth offer a contemplative insight into the idea of family and challenge many societal conventions.

49. Asako I and II (2018)

The film fraternity at International film festivals took notice of Ryusuke Hamaguchi for his powerful, Ozu-like five-plus-hour drama about the dynamics of friendship and marriage in the lives of young Japanese women. However, he rose to maddening popularity not until recently with his deeply meditative and confounding Drive My Car, which earned him an award for the best international feature film at the 94th Academy Award.

Related to Best Japanse Films – Ryusuke Hamaguchi Shares Criterion Top 10 Films

Hamaguchi’s lesser-known but masterful work Asako I & II takes a mystic plunge into the romantic paradigm, trying to examine the innate quality of a person that makes them fall in love and out of it. Without giving away any of the major plot points, Asako’s mystifying narrative is perfectly matched by Erika Karata and Masahiro Higashide’s mature performances, making you believe in what might appear gimmicky on paper.

50. Mother (2020)

Tatsushi Omori’s disturbing drama offers a hard-hitting look at bad parenting similar to Nagisa Oshima’s Boy (1969), and Yoshitaro Nomura’s The Demon (1978). The film revolves around a toxic matriarch named Akiko. The little and fragile son, Shuhei, is the victim of the extremely manipulative Akiko. She entangles herself in terrible short-term relationships and gets herself repeatedly abused in the process. At times, she neglects her kid, but most of the time, she uses Shuhei to her advantage. Shuhei’s grandparents take pity on him. However, it’s hard to break the toxic co-dependency between Akiko and Shuhei.

The narrative follows Shuhei growing up from a kid to a teenager, and his mother’s abusive behavior only intensifies gradually, leading to a tragedy. Omori’s Mother is a film that’s very hard to digest. The volatile and manipulative relationship between Akiko and Suhuei is portrayed in an extremely complex manner. It shows how growing up in an unstable household could impact a child’s outlook on the world and his/her idea of love and intimacy. The emotional truth of Mother is so raw that it serves as a lacerating movie experience. And it’s all perfectly held together by the phenomenal performance of Masami Nagasawa (Our Little Sister) in the titular role.

Stream Mother (2020) on Netflix

51. Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy (2021)

Berlin Silver Bear winner Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy is a triptych of short films, each running around for 40 minutes and each dealing with stories of love that are determined by twists of fate and coincidences. To elaborate on any of these three tales would spoil the fun as well as the profundity of the experience. Built out of seemingly ordinary moments, Ryusuke Hamaguchi smartly questions us about how much of our lives’ life-changing events unfold based on chance encounters.

Perhaps because the staging is ordinary and the performances are absolutely flawless, the twists in each narrative never come across as contrived. Moreover, we need to take into account that these are tales of love and attraction, stuff that makes us act more spontaneously and sometimes irrationally. In that spontaneity of human behavior, Hamaguchi finds rich context and depths. Finally, unlike most portmanteau pictures, all three stories are uniformly excellent.

52. Drive My Car (2021)

Ryusuke Hamaguchi constructs deeply introspective and contemplative drama that demands your attention and your deep emotional involvement. His films, in general, will feel like reading a long novel on an uncomfortable couch during summertime. It takes its own sweet time to build, moves at a glacial pace, and makes you uncomfortable in between. And ‘Drive My Car,’ based on Haruki Murakami’s short story of the same name from a collection of short stories in Men Without Women, is precisely what you expect from a prolific filmmaker who gave us Happy Hour.

Related to the Best Japanese Movies – Drive My Car Movie Explained: Ending & Themes Analyzed

A theater actor/director – Yusuke Kafuku (Hidetoshi Nishijima) – loses his beloved wife in unforeseen and tragic circumstances. In order to put together his life back, he agrees to direct a theater play at a provincial coastal town. It’s a play that’s based on Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya. At the theater’s insistence, he is given a driver, Misaki, who drives him to the theater in a red Saab and back to a rented house on a beach. Misaki carries her own personal scars. The to-and-fro journey eventually becomes a gateway for secrets to spill, emotions to simmer, and profound conversations ensue as both the characters confront their emotional & psychological predicament. It’s simple to look at but profound for those who submit to it.

53. Perfect Days (2023)

German filmmaker Wim Wenders’ endless love for Japan and architecture, led him to receive an invitation from the Tokyo Toilet Art Project to create a series of short documentaries on Tokyo’s idiosyncratic and artistic public toilets. The end result was not a documentary but a soulful fictional work on a cleaner of toilets in Tokyo. The beautifully restrained performer, Koji Yakusho, plays Hirayama, a janitor of few words who finds contentment in life’s routines and simple pleasures. Wenders, who co-wrote the script with Takuma Takasaki, doesn’t turn “Perfect Days” into a mere celebration of mundanity.

There are many layers to this man out of time, which are never explained but beautifully hinted. Wenders evokes a longing for a simpler life without downplaying Hiyama’s struggles. We are made aware of the tough journey he had embarked on to create a ‘simple’ life. There are moments that briefly dismantle his inner peace or the ‘perfect days.’ Yet, the way Hirayama embraces pain and joy (and all the emotions in between) gives us an unforgettable portrait of someone living in the present.

54. Godzilla Minus One (2023)

With the emergence of the MonsterVerse franchise, Godzilla has become a not-so-threatening presence in smash-’em-up monster flicks. Takashi Yamazaki’s 33rd Toho Godzilla film revisits the monster’s horror-infused origin tale. It balances captivating moments of monster rampage with a human story of pathos and redemption. “Godzilla Minus One,” released in the seventh year of Hondo’s “Gojira,” is set in the immediate post-war era and revolves around former Kamikaze pilot Koichi (Ryunosuke Kamiki). He suffers from survivor’s guilt, although he forms a makeshift family with young Noriko (Minami Hambe), who cares for an orphaned infant. But Godzilla’s emergence from the ocean multiplies the struggles of ordinary Japanese eking out a living in the firebombed Tokyo.

Yamazaki’s film follows the classic monster movie template, which, unlike recent Hollywood kaiju flicks, explores significant themes and features characters with considerable depth. The film’s exquisite VFX (only a fraction of a Hollywood monster movie budget) fully demonstrates the rage of the radioactive god. At the same time, Yamazaki’s rich emotional storytelling contributes a lot to the film’s staying power.

55. The Boy and the Heron (2023)

My immediate reaction to the first thirty minutes of “The Boy and the Heron” is that it’s not quite the Miyazaki masterpiece like “My Neighbor Totoro” or “Princess Mononoke.” Nevertheless, any Studio Ghibli or Miyazaki film is a gift to cinephiles, and as “The Boy and the Heron” gently submerges into the familiar yet invigorating lores of its magical world, I can help but surrender myself to the enchanting Miyazaki-esque themes and characters. The film’s Japanese title refers to Genzaburo Yoshino’s 1937 novel, “How Do You Live?” although it’s not an adaptation of the novel. “The Boy and the Heron” is set in wartime Japan and follows Mahito, the titular boy whose mother dies in the Tokyo firebombing.

Mahito’s father, Shoichi, remarries his late wife’s sister, Natsuko, and they move to the countryside since Shoichi is in charge of a factory constructing fighter plane parts. Left adrift in changed circumstances, the lonely and grief-ridden Mahito embarks into a magical realm, guided by the eponymous bird, to look for his mother. While Miyazaki often draws from his childhood and memories of war, “The Boy and the Heron” has a lot more autobiographical elements than usual. By the end, the film becomes a fascinating allegory for artistic creation. But as always, the greatest strength of a Miyazaki movie is the exacting realism of his animated world. From Mahito running amidst an inferno-like Tokyo to the variety of anthropomorphic creatures in the magical world, Miyazaki and his animators continue to astound us with the imagery.

Checkout – Where To Stream All 2022 Oscar-winning Movies

Honorable Mentions:

Tony Takitani (2004)

Jun Ichikawa’s Tony Takitani is said to be the first full-length adaptation of a Haruki Murakami story. It’s interesting to note that Mr. Ichikawa has earlier adapted Banana Yoshimoto’s short Japanese novel ‘Goodbye Tsugumi.’ Both Murakami and Yoshimoto often weave quiet yet complex emotional tales that can’t be easily transitioned into film form.

Tony Takitani will be largely memorable for cultivating the essence of Murakami’s style on the screen. Its beautiful haiku aesthetics and stellar performances come close to conveying the ineffable emotional expressions, emotions we seem to know and feel but can’t really explain. Or the more we try to put it into words, the more ineffable it becomes. Tony is a familiar Murakami man: a lonely man who is lost, existentially as well as emotionally. While the film may not be very emotionally involved, it’s the slow horizontal camera movements that come at the end of each scene – conveying the passage of time – that keep us hooked.

Rent-a-Cat (2012)

Naoko Ogigami is one of the important Japanese commercial filmmakers. Her delightful, feel-good films often revolve around underdogs and outcasts of modern Japanese society, and she focuses on their stories of companionship and love. Ogigami’s beautiful little movie Kamomi Diner is set around a Japanese diner in Finland and its quirky owner, Sachie. The film’s tone and characterizations reminded me of the works of my favorite filmmaker, Aki Kaurismaki. But Ogigami’s 2012 film Rent-a-Cat is easily her most accessible and best work.

It’s a finely restrained examination of social solitude. It revolves around an eccentric young woman named Sayako, whose distinct quality is that she attracts cats. Hence, she comes up with a unique business plan: renting out cats to lonesome people. Ogigami crafts the right kind of fluffy narrative piece that will definitely extract a few chuckles and happy tears from you.

The Night is Short, Walk on Girl (2017)

Masaaki Yuasa’s animated stories can be termed ‘wild spectacles.’ They’re where the strange and surreal come together to examine the absurdities of the human condition and our complex emotions. The 2004 anime Mind Game – a bizarre journey of a young man’s self-discovery—brought him wide critical acclaim. A decade-and-a-half later, Masaaki’s unrestrained explosion of expression continues to take us on joyous wild rides.

Night is Short, Walk on Girl also has a weird assortment of character-centric adventures rather than a coherent narrative. It revolves around a fun-seeking young student, Otome, who goes out with her friends for a night of partying and drinking. In the course of the night, she explores a lot and meets an array of improbable characters. Yuasa’s works can be so chaotic that one needs to surrender and allow it to flood one’s senses. Hence, his works haven’t always worked for me. Nevertheless, I am curious to see how it all works in the second viewing.